If you’re an avid marine sport angler, you have most likely seen the smiling faces and brown polo shirts of California Recreational Fisheries Survey (CRFS) samplers. Since its inception in 2004, CRFS has grown into one of the state’s largest and most important survey efforts. Survey samplers are tasked with collecting data about both recreational fishing catch and effort.

Annually, CRFS samplers make direct contact with 68,000 fishing parties at over 400 sampling sites between the California-Oregon state line to the California-Mexico border. A separate but related telephone survey effort contacts an additional 26,000 anglers. A program of this large scale is necessary because recreational fishing effort and success rates are highly dynamic – a large sample size is needed to adequately estimate catch and effort. Recreational fishing effort is also very challenging to predict, as it can be affected by many factors (weather, gas prices, time of year, fishing seasons, etc.). But the recreational sector accounts for a significant portion of overall marine harvest, so it’s essential to collect that data to produce reliable estimates of harvest.

CRFS is part of a larger effort to estimate recreational catch and effort on the west coast and is integral to the national effort conducted by the National Marine Fisheries Service’s Marine Recreational Information Program. This partnership allows CRFS methods to be periodically peer reviewed by expert consultants throughout the country. This review provides certification that the methods meet or exceed national standards and fisheries management needs, and can recommend the use of new methods to address changing needs or to capture emerging fisheries.

There are three parts to the survey. The first is the field sampling component. This consists of in-person interviews conducted for four different fishing modes – beaches and banks, man-made structures, private/rental boats, and commercial passenger fishing vessels. Field survey questions are specific to catch and effort data during daylight hours at publicly accessible sites. The second part of the survey is the telephone survey. Anglers are randomly selected monthly through the state’s online Automated License Data System (ALDS) and asked about effort data (the number of fishing trips taken) at beach and bank sites. The telephone survey also collects data from private boats returning to sites not sampled during the field survey, and private boats returning at night. The third part of the survey is collection of data from commercial passenger fishing vessel logs. Captains submit this information for every trip, and the data is used together with field sampling data to estimate overall fishing effort.

All of this information is used in many ways. In addition to CDFW, the Fish and Game Commission and the Pacific Fishery Management Council use the data to:

- Track in-season catches against annual harvest limits, especially for certain over-fished groundfish species, such as Yelloweye and Cowcod rockfish.

- Produce in-season salmon estimates in coordination with the CDFW Ocean Salmon Project.

- Aid the development of regulations, including fishing season, bag limits, minimum size limits and depth limits.

- Assess stocking needs for individual fish species.

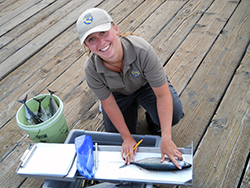

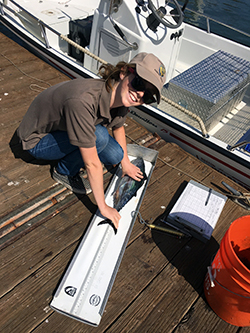

How can you help? There are two ways! If you encounter a CRFS sampler in the field, please cooperate and answer the interview questions truthfully. Take the time to allow the sampler to examine and measure any catch. Recreational anglers, particularly those who fish frequently, are more likely to encounter CRFS samplers. Every fishing trip is unique — different target species, success rates, different locations, different gear, etc. — so we ask anglers, “Even if you have completed this survey before, please cooperate each time you are asked!”

Secondly, if you receive a phone call, please say “yes” to the CRFS telephone surveyor. Data collected through this telephone survey is used to estimate fishing effort that cannot be estimated any other way.

Personal contact information is always kept confidential, and the information that is collected becomes part of a public database. To learn more about the CRFS, access the database or download related flyers and brochures, please visit www.wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Marine/CRFS.