They came from as far away as Los Angeles, Truckee and Crescent City. They showed up with their shotguns, bird dogs and blaze orange and returned over, and over, and over again.

It was a turn-back-the-clock experience at the Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area during California’s 2024-25 hunting season. The wildlife area set a new record for its wild pheasant harvest at 687 birds and, for one season at least, rekindled memories of the Sacramento Valley as the wild pheasant hunting destination it used to be in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

“We probably had more pheasant hunters this season than the previous two years combined,” said Chris Rocco, Wildlife Habitat Supervisor I at the Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area, who has worked at the property since the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) opened it to public use in 1996.

“I could tell it was going to be a real good pheasant year, a fantastic year, I just didn’t anticipate it was going to be as good as it was,” Rocco said. “I was predicting 350, maybe 375 birds (harvested), but we blew past those numbers by the third week of the season.”

The hunting public got its first glimpse of the potential not during the November pheasant opener, but rather when the area opened to dove hunting September 1. The wildlife area’s dove hunters couldn’t stop talking and texting about all the wild pheasants they were seeing.

For more than a decade, the Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area, with the downtown Sacramento skyline as its backdrop, has been California’s top wild pheasant producer, accounting for about half of all the wild pheasants taken on public land throughout the state.

The area’s annual wild pheasant harvest usually fluctuates within the 225 to 325 range. (Only male wild pheasants may be taken.) The previous high of 606 wild roosters was reached during the 2003-04 hunting season immediately after the wildlife area expanded and opened 5,000 additional acres to hunting for the first time. Although considerably smaller in size at the time, the wildlife area harvested just 19 roosters when it first opened to public hunting for the 1997-98 season.

Today, the Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area is California’s largest Type A state-operated wildlife area at almost 17,000 acres. As much as 40 percent of the area consists of various upland habitats needed by pheasants, songbirds, nesting ducks, pollinators and other species. This type of habitat has largely disappeared from the Sacramento Valley landscape. Neighboring farms and private duck clubs add to the habitat footprint.

Yolo’s expanse of upland habitat, however, doesn’t fully explain the record pheasant harvest, which more than doubled the 304 birds taken during the 2023-24 hunting season. Although the area hosts some planted-bird pheasant hunts for new hunters and youth hunters each season, those pen-raised birds aren’t included in the area’s pheasant count.

Listening to Rocco, a combination of nature and nurture led to the record harvest.

On the nature front, two years of wet winters and springs in 2023 and 2024 led to back-to-back flooding of the wildlife area, which is also used for flood control. That temporary flooding benefits ground-nesting birds such as pheasants, Rocco explained, as the floodwaters kill or force out the four-legged predators hardest on pheasants, particularly skunks. The upland habitat and pheasants return quickly when the floodwaters recede while the predator populations take more time to recover.

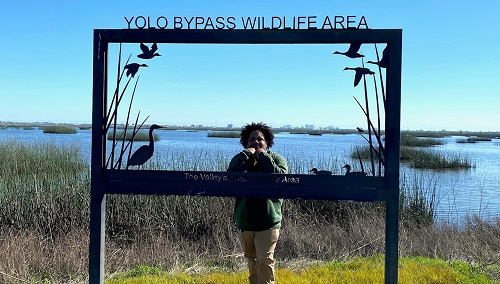

CDFW Seasonal Aid Darian Marico Clark-Stinson stands behind the Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area metal sign.

CDFW Seasonal Aid Darian Marico Clark-Stinson stands behind the Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area metal sign.

“Normally, we are lucky to have two hatches, but we actually had three hatches this last year,” Rocco said. “We had birds coming off the nest in August, which is not common. And the survival rate was so high I was seeing broods of eight to 10 chicks.”

Video: Not just pheasants! The Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area set an all-time-high harvest for geese and cinnamon teal in 2024-25. The area’s mallard harvest at 844 birds was the second-highest total in area history. CDFW’s Darian Marico Clark-Stinson has the complete season recap, including free roam and blind totals, in a special “Yolo Alert” report.

On the nurture front, the Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area team, led by CDFW Senior Environmental Scientist Supervisor Garrett Spaan, applies a light farming touch to the landscape, leaving edge habitat for protective cover and wildlife travel corridors, integrating water into upland fields to foster broadleaf vegetation that produces the invertebrates, notably grasshoppers, pheasant chicks and other bird species need in the early stages of their lives.

“Even in dry years, it’s important for us to maintain adequate summer wetland habitat and wetland irrigation for moist soil management across the area to benefit pheasants and other wetland-dependent species,” Spaan said.

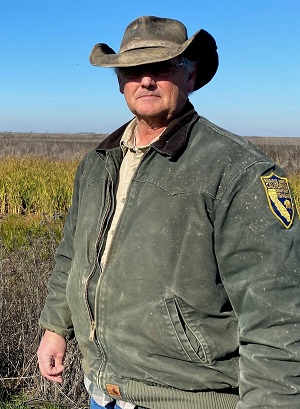

CDFW's Chris Rocco.

CDFW's Chris Rocco.

Part of the habitat management strategy is also practical necessity. The area has only three full-time employees working in the field and five seasonal employees to manage CDFW’s largest Type A land holding.

“We’re dirty farming out here,” Rocco said. “It’s kind of the old-style farming where everywhere you have a ditch, you have vegetation growing on it. Everywhere you have a fence, you’ve got a windrow growing on it. You’ve got the edges of fields out here you can’t get water to or you can’t disk, so we just leave it. That’s when you get wildlife utilization.”

Rocco takes pride in the area’s wild pheasant numbers as an indicator of healthy uplands.

“Everyone is talking about our pheasants right now, but we’ve got Swainson’s hawks everywhere, we’ve got a massive deer population here with some monster bucks just hanging out. We’ve got turkeys coming in, giant garter snakes and a lot of endangered species out here,” Rocco said. “This is a wildlife area in the broadest sense, and we manage it so that everything benefits.”

Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area Wild Pheasant Harvest Through the Seasons

2024-25 – 6872020-21 – 306

2023-24 – 3042019-20 – 229

2022-23 – 2632018-19 -- 361

2021-22 – 2192017-18 – 185

Media Contact:

Peter Tira, CDFW Communications, (916) 215-3858