VegCAMP staff researching at Carrizo Plain, San Luis Obispo County

VegCAMP staff working at Modoc Plateau, Modoc County

Lightning-caused fire witnessed by staff, Mono County

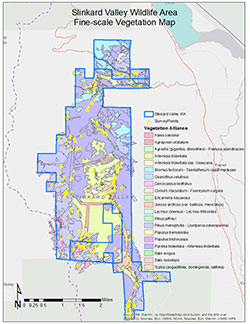

Slinkard Valley Wildlife Area vegetation map

California is home to more than 6,500 plant species, which offer sustenance and shelter to more than 1,000 animal species (this figure doesn’t include invertebrates).

In fact, part of the mission of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) is to manage the habitats upon which our fish and wildlife species depend. The cornerstone of those management efforts is knowledge of the plant assemblages that are unique to each habitat – where these natural communities are located, how prevalent (or rare) they are, and monitoring how their distribution may shrink or grow over time.

CDFW has three vegetation ecologists (Rachelle Boul, Betsy Bultema and Jaime Ratchford), a geographic information systems (GIS) specialist (Rosie Yacoub) and a unit supervisor (Diana Hickson) dedicated to exactly that task. Known as the Vegetation Classification and Mapping Program (VegCAMP), this team works year-round to identify, record and map all of the natural communities (also known as vegetation types) that grow in California’s 163,000 square miles. VegCAMP also relies on the mapping expertise of four contracted employees, paid through an arrangement with California State University, Chico.

According to Hickson, having a complete, reliable map of California’s vegetation is an invaluable scientific tool. “We need knowledge of where the vegetation is in order to make good management decisions, such as determining the best place to put a preserve, for example,” she says.

VegCAMP tackles this task by sampling, classifying, defining, naming and mapping the natural communities of an area – such as the Suisun Marsh, Point Reyes, Western Riverside County or the Mojave Desert. Some mapping areas encompass an entire eco-region (the Mojave Desert mapping area, for example) while some are as small as a 2,000-acre ecological reserve.

The process of classifying and mapping a CDFW property, for example, generally requires eight to 10 people to survey the property, taking detailed notes and pictures to describe the vegetation at different locations. The “boots on the ground” effort doesn’t have to cover every square inch, fortunately. The process requires collecting vegetation samples from a small portion of the mapping area (depending on the complexity), then extrapolating to determine the most likely makeup of the entire area. The data is then brought back to the office to be classified, and each location visited can be given a vegetation name. These locations on the ground are compared to aerial imagery and lines are drawn around each community type and labeled. Another measure of checks and balances is to have a second field crew survey known locations of each community, without having knowledge of the previously mapped attributes.

All of this information is entered into the VegCAMP database, where classification software and GIS tools allow users to gain a tremendous understanding of what comprises a particular area. “One map contains many different attributes,” Hickson explains. “For example, we can query the polygons (each mapped ‘patch’) to show acreage of conifer types, and then we can narrow the search to those conifer types that are tall or short, those that are regenerating or those that have a shrub layer under them. That’s the power of GIS layers.”

The data collected and recorded by the VegCAMP team has far-reaching implications, and is used by other agencies, nonprofits and partners as well.

Seeing the practical application of their work is a satisfying payoff for Hickson and her crew. For example, the VegCAMP team spent several years meticulously mapping Mendocino County’s Pygmy Forest, which is dominated by a few conifer species that grow to a height of six feet or less, due to nutrient-poor soil that saturates in the winter and dries completely over the summer. Over time, the team produced a comprehensive map that showed how much vegetation had been lost to residential development and cannabis grows, as well has how much remained.

“As a result of our mapping, the county recognized the need to require more environmental assessment for proposals for development in that habitat,” Hickson explained. “It’s raised awareness of the vulnerability of that vegetation type.”

Vegetation ecologist Rachelle Boul also finds satisfaction in her work with VegCAMP. Her mapping efforts have largely been focused in the Suisun Marsh area in Solano County. This highly managed area is home to rare species such as the salt marsh harvest mouse, and CDFW works with the California Department of Water Resources and private duck clubs to maintain habitat for them while also allowing access for duck hunting. Here, VegCAMP remapped the vegetation every three years in order to determine if there had been any negative impact.

Boul noted the importance of aerial images, including those taken by satellite – VegCAMP has access to the photos taken by the US Department of Agriculture’s National Agriculture Imagery Program – and drones. “You can only make a vegetation map as good as the imagery that you interpret from. It’s just made it so much easier to be more accurate and more fine scale,” she said.

Boul says that it’s the diversity of her duties – from field work to data analysis to mapping vegetation and finally sharing that data with CDFW partners – that keeps her motivated and passionate about her job.

Being able to spend time in nature is certainly a perk for the VegCAMP ecologists but that’s not to say there aren’t job-related hazards. Both Hickson and Boul remember a particularly harrowing day in August 2017, when they were field mapping the Slinkard/Little Antelope Wildlife Area in Mono County, and a lightning strike touched off a fire. The VegCAMP team reported the fire immediately and were soon joined by CalFIRE helicopters and ground crews. Map-making took a back seat that day to field safety and group communication.

Despite the size and length of the fire (nearly 9,000 acres and several days), it didn’t really impact the work of VegCAMP. Nerves may have been rattled, but fortunately nearly all of that mapping area (work still in draft form) was untouched by flames.

###

Media Contact:

Tim Daly, CDFW Communications, (916) 201-2958

(CDFW Photos)