Does the Western pond turtle (Actinemys marmorata), a freshwater species native to the Pacific Coast, hold secrets to survive climate change and adapt to rising sea levels? CDFW biologists want to know and have partnered with UC Davis and the Department of Water Resources to conduct a long-term study in Solano County’s Suisun Marsh to better understand the aquatic reptiles.

Officially, the Western pond turtle is a Species of Special Concern in California because of declining populations brought about by habitat loss, degradation and competition from that pet store favorite – the non-native, red-eared slider. The pet slider turtles are often released into the environment by their owners after outgrowing or outliving their welcome. They also outgrow and out-compete the medium-sized western pond turtles for food and critical basking spots. Western pond turtle populations are faring even worse in Oregon and Washington.

And yet in the Suisun Marsh, with its brackish water and high salinity, the Western pond turtle appears to be thriving. The Suisun Marsh, ironically, may now be home to one of the strongest populations of Western pond turtles on the West Coast.

“It’s just a really unique population in a place where we didn’t expect to see a freshwater species,” said Mickey Agha, the UC Davis Ph.D. student leading the  university’s turtle research with Dr. Brian Todd, an associate professor in the UC Davis Department of Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology.

university’s turtle research with Dr. Brian Todd, an associate professor in the UC Davis Department of Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology.

As if to underscore the point, researchers this summer collected a turtle with a barnacle attached to its shell – a testament to the marine-like environment to which the Suisun Marsh turtles have adapted.

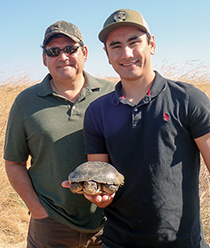

Researchers also have been impressed with the age, health and size of the individual turtles. At 1 ½ to 2 pounds and with an upper shell that stretches up to 8 inches in length, researchers are discovering some of the largest Western pond turtles ever recorded in California.

“Looking at the ones we’ve collected, we’re seeing a lot of healthy turtles in good body condition,” said Environmental Scientist Melissa Riley, who is leading CDFW’s efforts.

The research began in the summer of 2016 with scientists trying to get a basic sense of turtle population numbers. The turtles are trapped in baited, floating hoop nets, their size, weight and age recorded. Before being released, each turtle is marked by filing a unique pattern of small notches along the edges of the upper shell. More than 125 turtles have been recorded in the project’s database.

Turtle trapping is taking place on three sites at the Suisun Marsh in and around the Grizzly Island Wildlife Area. Biologists are particularly interested in turtles at the Hill Slough Wildlife Area along Grizzly Island Road as 500 acres there will soon be restored to tidal marshland. Biologists plan to affix tiny, solar-powered, GPS tracking devices to some of the turtles to study their movements and see how they respond to the increasingly saltwater environment at Hill Slough and other parts of the marsh.

“That’s one of the many questions we have,” Agha said. “If sea level rise occurs, what happens to these turtles?”