Kerstin Wasson is leading the Olympia oyster restoration at Elkhorn Slough. Kerstin Wasson photo.

Scientists are working hard so that a new generation of Olympia oysters may one day line the mudflats at the Elkhorn Slough Reserve.

Volunteers Ken Pollak and Celeste Stanik join Dr. Chela Zabin to improve the native oyster habitat at Elkhorn Slough. Kerstin Wasson photo.

Suspended gaper clam shells hang in aerated laboratory tanks, home to what scientists hope will be a new generation of Olympia oysters at the Elkhorn Slough Reserve.

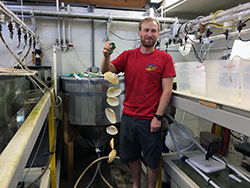

Graduate student Dan Gossard, at CSU’s Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, shows off one of the clam shell “mobiles” on which the Olympia oyster larvae will attach when suspended in aerated tanks.

Kerstin Wasson points out Olympia oysters along the banks of the Elkhorn Slough Ecological Reserve in Monterey County.

For the first time in California history, scientists are turning to shellfish farming techniques to restore native oyster populations.

The groundbreaking research is taking place with Olympia oysters at CDFW’s Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve in Monterey County, in partnership with the California State University’s nearby Moss Landing Marine Laboratories and its new Center for Aquaculture.

Olympia oysters and other shellfish were once so abundant at Elkhorn Slough that Native Americans living there had multiple processing centers along the estuary’s banks to handle their harvest. Olympia oysters have disappeared altogether from many places along the California coast and their numbers at Elkhorn Slough have dwindled so low – estimated today at just a few thousand oysters – that scientists fear they may no longer be able to reproduce in the wild. Not since 2012, they say, have Elkhorn Slough’s wild oysters produced any offspring.

A combination of factors is believed to have caused the population drop over time, including poor water quality because of agricultural runoff from nearby farms and alterations to the landscape and tidal flow from generations of farming and other human activity prior to the area becoming protected in a series of conservation purchases beginning in 1971. An infusion of freshwater from last year’s rainy winter caused a severe oyster die-off and spurred biologists into action.

“This is an iconic species in our estuary in danger of disappearing,” said Kerstin Wasson, Research Coordinator at Elkhorn Slough, where she has worked for 17 years with funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the federal partner in the Elkhorn Slough Reserve. “These oysters fed native people here for 7,000 years.”

In late August, dozens of Olympia oysters were gathered and brought to the Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, where 20 spawned successfully. A few hundred thousand of their microscopic offspring are now swimming in large, circular laboratory tanks and attaching themselves to gaper clam shells suspended on fishing line from the top of the tanks. The clam shells bearing young oysters will be bound together into makeshift reefs and returned to Elkhorn Slough early in 2018 to bolster the native population.

The research is being led by a small group of scientists, including Wasson and graduate student Dan Gossard with funding provided by the Palo Alto-based Anthropocene Institute. These are uncharted waters for California scientists, however, and a major assist is coming from the aquaculture industry itself. Peter Hain of the Monterey Abalone Company has worked closely with the two researchers to set up the laboratory facility for the Olympia oysters and help with their care and feeding.

Due partly to their small size – an individual Olympia oyster is about the size of a 50-cent coin – and slow growth, Olympia oysters hold little appeal and little potential profit for most commercial oyster farmers who focus on larger Pacific varieties, many native to Japan. Taylor Shellfish Farms in Washington State is the only known commercial producer of Olympia oysters.

Wasson welcomes interest and support from aquaculture and hopes growers might one day add the native oyster to their operations. She believes even a niche commercial market for Olympia oysters could have positive implications for wild populations, enhancing recruitment, broadening scientific knowledge and a general appreciation for the native mollusk by the public.

Other efforts to save wild oyster populations in California and elsewhere have focused on building jetty-like artificial reefs constructed from oyster shell contained in plastic mesh.

Wasson prefers that more natural materials be used as part of the oyster restoration efforts underway at Elkhorn Slough, creating small clusters of oysters rising above the mudflats.

“I want this place to look like it did 200 or even 2,000 years ago,” she said.

Top photo: A huge influx of fresh water during winter 2017 resulted in an Olympia oyster die-off and spurred biologists into action.