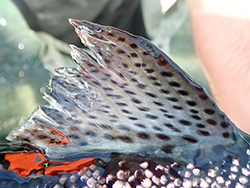

Close-up of adult spring-run Chinook salmon dorsal fin.

Adult spring-run Chinook salmon inform river restoration decisions by their habitat use and preferences.

Adult spring-run salmon are carefully selected for release based on their sexual maturity.

Spring-run Chinook salmon released into the San Joaquin River are outfitted with three tags including a colored T-bar tag for visual identification.

Fresno County may seem an unlikely setting for salmon restoration and research, but some of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (CDFW) most ambitious work with salmon anywhere is taking place in the heart of the parched Central Valley.

Since September, CDFW fisheries biologists have been spawning spring-run Chinook Salmon broodstock in the shadow of Friant Dam on the San Joaquin River. This season, CDFW staffers spawned 100 mature females that ranged in age from 3 to 6 years old producing about 290,000 eggs.

It’s all part of an unprecedented, multiagency effort to restore an extinct, spring-run Chinook Salmon run to the San Joaquin River that is happening alongside river restoration efforts to make the river more salmon-friendly for a fish listed as threatened under both the state and federal Endangered Species Act.

Historically, spring-run Chinook Salmon were the most abundant salmon species in the Central Valley. Today, there are so few fish broodstock used for spawning comes from eggs collected at CDFW’s Feather River Hatchery in northern California. Meanwhile, construction is underway on a spring-run Chinook Salmon hatchery at the base of Friant Dam to support future runs of San Joaquin River salmon. The hatchery is scheduled to be completed in 2019.

During spawning, each female is crossed with four males to maximize genetic diversity. Samples of ovarian fluid are collected and sent to the CDFW’s Fish Health Lab for virology and bacterial analyses. Any egg lots determined to be potentially infected with pathogens are excluded from CDFW’s captive rearing program.

In June and August, 179 captive-reared adult fish – 59 females and 120 males – were released into the San Joaquin River to monitor what parts of the river the salmon prefer for holding and natural spawning.

Prior to release, each fish was outfitted with three tracking devices – an electronic passive integrated transponder (PIT) tag for individual identification, a colored, T-bar tag for visual identification, and an acoustic transmitter so their movements in the river can be monitored and recorded. Their habitat use and preferences inform river restoration efforts.

Spring-run Chinook Salmon spawn in the fall from mid-August through early October. So far, biologists have found 37 constructed redds – or salmon nests – in the San Joaquin River indicating some of the released salmon found enough cool water in the heavily damned and diverted river system to survive the Central Valley’s furnace-like summer and are now actively spawning in the river.

CDFW Photos by Travis VanZant. Top Photo: Prior to their release into the San Joaquin River this past summer, adult spring-run Chinook salmon were outfitted with acoustic transmitters so their movements in the river can be monitored and recorded.