Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep are an endangered species under Federal and California law. There is a real opportunity to recover Sierra bighorn because their habitat is intact and there is broad public and agency support for the effort. Sierra bighorn are one of only two only federal endangered species in Yosemite National Park and Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Parks (along with the mountain yellow-legged frog); these parks are excited to see this iconic mammal restored as part of the native fauna within their boundaries. Down-listing goals can be met in the next decade if recovery actions are implemented. Translocations to augment newly created herd units are still needed while the existing herds that serve as translocation stock must be protected. Recovery goals are outlined in the Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Recovery Plan (PDF).

Current Population Update

The population of Sierra bighorn experienced about 55% mortality during the extreme winter of 2022-2023. Snow water-equivalent in the southern Sierra Nevada exceeded 400% of normal in some locations. After accounting for lamb recruitment during the summer of 2023, we estimated that the population declined by 40% from the summer of 2022.

Two factors account for the severe mortality in 2022-23. Sierra bighorn who winter at high elevations to avoid predation were impacted by heavy snow that kills bighorn through avalanches and starvation; we really have no way to manage this type of mortality. Bighorn who winter at low elevations as they attempt to escape extreme weather are at much greater risk of predation, and during 2022 we documented at least 42 bighorn sheep that were killed by mountain lions.

Sierra bighorn, when protected from excessive predation, have shown a propensity to rebound from severe winters. They exhibit a remarkable ability to persist in an incredibly harsh environment.

The Recovery Program intensively monitors mountain lions to determine which lions prey on Sierra bighorn. The mountain lion population in the eastern Sierra Nevada is the largest documented in decades, and in 2023 we estimated there were 55 lions. We currently use translocation of lions as an alternative to lethal removal.

During 2022-2024, we translocated 14 female and subadult lions; the 88% survival rate of those translocated lions exceeds that typically observed in unmanaged populations. Moving lions that prey on Sierra bighorn, particularly on low elevation winter range, is essential for protecting translocation stock needed to augment small bighorn herds.

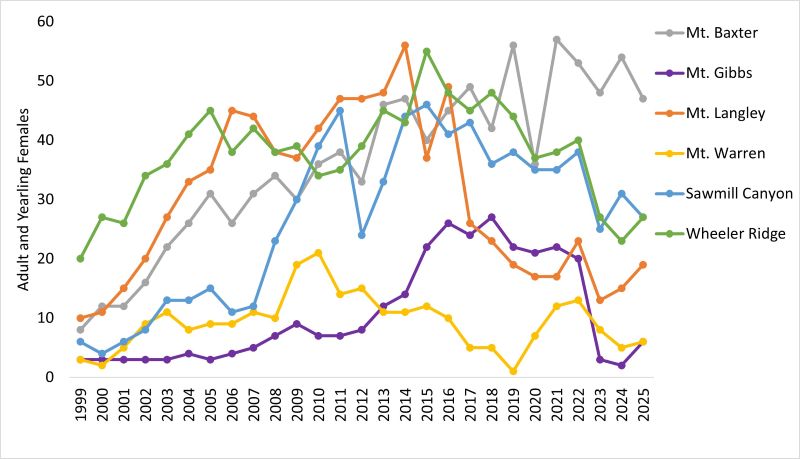

Population Growth for Each Herd Unit (Ewes)

In bighorn sheep, the number of adult ewes determines how quickly a population can grow or recover from losses. Because of this, the health of a population is often gauged by the number of ewes present. This graph shows population trajectories for adult and yearling females from 1999-2025 based on a combination of population estimates (marked resight and minimum counts) for 6 herds in the Sierra with annual population data.

Numerical Recovery Goals

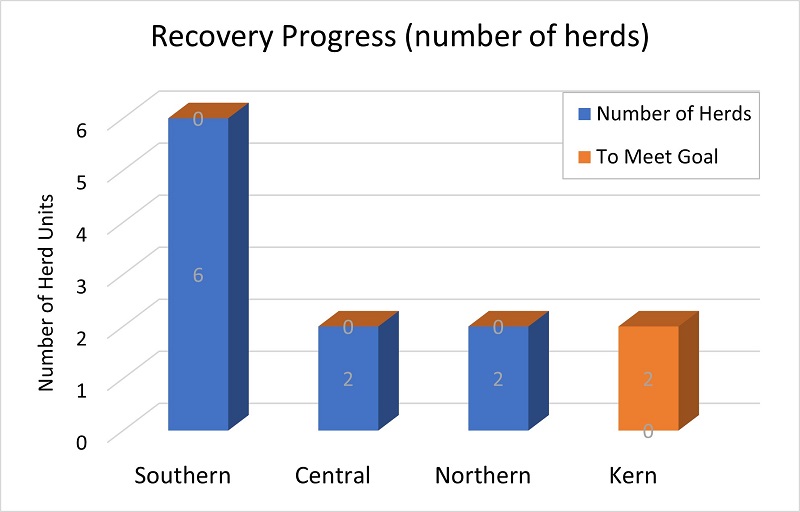

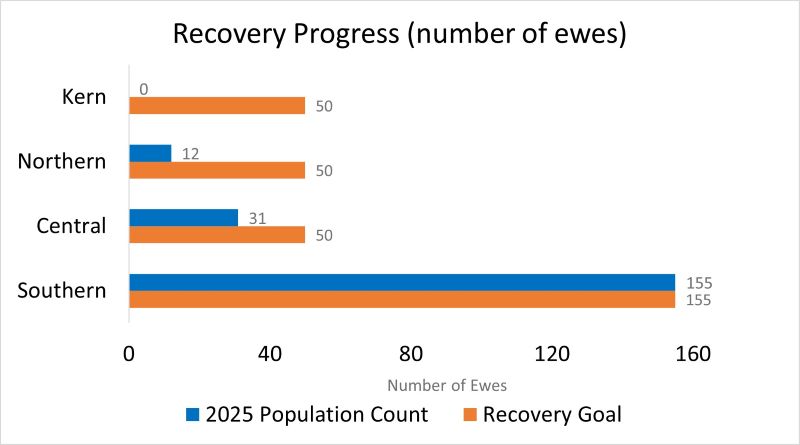

The population goal for downlisting to threatened status is 305 females (for >1 year).

The population must be distributed among 12 of 16 herd units within the 4 recovery units. For delisting the required number of bighorn sheep must persist for a minimum of 7 years without management intervention.

The numerical and herd unit / recovery unit occupation is tabularly summarized below. Achieving final recovery goals will require additional translocations and augmentations. These ewes may potentially be supplied by the Mt. Baxter, Sawmill Canyon, and Wheeler Ridge herds. Therefore, surplus animals must be available for removal from these herds (see map of herds (JPG)).

| Recovery Unit |

Herd Unit |

Downlisting / Delisting

Criteria

Recovery Unit #Ewes |

Current Population

Recovery Unit

(2025) |

Current Population

Herd Unit

(2025) |

Plan to Achieve

Numerical Goals |

| Kern |

Laurel Creek* |

50 |

0 |

0 |

Translocation |

| Big Arroyo* |

0 |

Translocation |

| Southern |

Olancha Peak* |

155 |

161 |

45 |

Natural growth |

| Mt. Langley* |

19 |

Natural growth |

| Mt. Williamson* |

8 |

Natural growth |

| Bubbs Creek** |

11 |

Natural growth |

| Mt. Baxter* |

47 |

Natural growth |

| Sawmill Canyon* |

27 |

Natural growth |

| Taboose Creek* |

4 |

Natural growth |

| Black Divide |

0 |

Translocation |

| Coyote Ridge |

0 |

Translocation |

| Central |

Wheeler Ridge* |

50 |

31 |

27 |

Natural growth |

| Convict Creek* |

4 |

Natural growth |

| Northern |

Mt. Gibbs* |

50 |

12 |

6 |

Natural growth |

| Mt. Warren* |

6 |

Natural growth |

| Green Creek |

0 |

|

| Twin Lakes |

0 |

|

| Cathedral Range** |

0 |

Translocation |

Key

| Symbol |

Description |

| * |

Required, currently occupied |

| ** |

Not Required, currently occupied |

Recovery Program Overview

The Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Recovery Program is specifically charged with implementing the recovery of Sierra bighorn, one of the rarest large mammals in North America. Additionally, CDFW is involved in the conservation and recovery of desert bighorn sheep in the Peninsular Ranges, another population listed under the Endangered Species Act. CDFW also manages the remaining desert bighorn sheep in California, allowing hunting where populations are healthy and can tolerate some harvest.

Historically, bighorn were distributed along the crest of the Sierra Nevada in California from Sonora Pass in the north to Olancha Peak in the south. Prior to European settlement, it has been estimated that there were more than 1,000 bighorn in the Sierra Nevada. However, the Sierra bighorn population was severely reduced during the 19th and 20th centuries because of diseases contracted from domestic sheep, forage competition with domestic livestock, and market hunting. By the late 1970s, there were only two geographic areas where bighorn were found (near Mt. Baxter and Mt. Williamson), with a combined population of 250. Between 1979 and 1988, CDFW translocated bighorn from the Mt. Baxter area to Wheeler Ridge, Mt. Langley, and the Mono Basin to reestablish herds in historic ranges. These recovery efforts were thwarted by another major population decline during the 1990s, attributed primarily to mountain lion predation and drought. By 1995 only about 100 bighorn remained in the Sierra Nevada. Sierra bighorn have been listed under the California Endangered Species Act (CESA) since 1974, but were uplisted from threatened to endangered in 1999 by the California Fish and Game Commission. In the same year, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) temporarily listed the subspecies as endangered on emergency basis under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) (Emergency ESA Listing Sierra Bighorn Sheep 1999 (PDF)). Final listing as endangered occurred early in 2000. CDFW was identified as the lead agency for Sierra bighorn recovery implementation. A team of stakeholders was then assembled and drafted a recovery plan.

Federal endangered status was sought for these bighorn because of a dangerously low population size and the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms. Two concerns were identified: the negative effects of mountain lion predation and the threat of a major respiratory disease epizootic that could result from contact with domestic sheep grazed on public lands adjacent to bighorn ranges. The Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Recovery Plan (PDF) identified 16 historic herd units grouped into 4 recovery units. The plan specified herd units that needed to be occupied as well as minimum numbers of females by recovery unit necessary for downlisting and delisting. Issues identified for management actions included losses to predation, factors limiting use of low elevation winter ranges, domestic sheep grazing, and unoccupied herd units. The plan also called for the development of regular demographic data on bighorn herds and identified areas of desired research. Recovery goals required to downlist to threatened are a minimum of 305 females distributed among the recovery units and the occupancy of 12 herd units; these conditions must persist unaided for seven years in order for the subspecies to be removed from the ESA.

To meet delisting requirements, recovery activities focus on understanding and managing factors influencing population performance and expansion of the distribution of these bighorn. Factors known or suspected to limit Sierra bighorn are risk of disease from domestic sheep, predation by mountain lions, forest succession, genetic diversity, severe weather, climate change, and reduced geographic distribution.

Currently the CDFW Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Recovery Program conducts winter and summer population surveys of all bighorn herds, evaluates nutritional status, monitors survival and habitat use patterns of more than 100 individuals, collects data from more than 80 GPS collars, and identifies resource selection patterns across the Sierra Nevada. The program also determines patterns of genetic variation across the subspecies, models risk of disease transmission from domestic sheep and goats, quantifies the effects of natural and prescribed fire on bighorn forage and habitat use, monitors mountain lion movements, predation rates and population numbers, implements and monitors translocations, and models bighorn response to potential management actions. Information acquired during these investigations is used to direct recovery activities.

Since its listing under the ESA, the Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep population grew from about 125 individuals in 1999 to over 600 in 2015. Subsequently, the Sierra experienced several years of heavy snowfall combined with heightened levels of mountain lion predation, and the Sierra bighorn population dropped to below 300 in early 2023. Of the 16 herd units identified as suitable habitat for Sierra bighorn, we currently only consider 9 to be occupied, based on the presence of ewes as well as rams. Additionally, a new herd unit not identified in the Recovery Plan, the Cathedral Range, is occupied by rams, but it is currently unclear if any ewes remain there to consider it a viable herd.

Learn More

Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Program

787 N. Main Suite 220

Bishop CA 93514

(760) 872-1171

asksnbs@wildlife.ca.gov