Predator monitoring and management is an integral part of the Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Recovery Program (see the 2025 Predation Management Plan). For Sierra bighorn recovery, the primary focus of predator monitoring and management is mountain lions, but program personnel investigate Sierra bighorn mortalities from all causes. Mountain lions kill bighorn sheep but may have little or no impact on population trend if predation is infrequent. Some mountain lions learn to specialize on bighorn sheep. Consequently, in some of the small, isolated populations of Sierra bighorn that now exist, predation can have a major impact on the growth rate of the population. For this reason, mountain lions are removed or relocated if they are considered a significant threat to the recovery of a Sierra bighorn herd. The goals with respect to predators are to monitor predation risks to Sierra bighorn, provide Sierra bighorn herds enough protection to ensure recovery, and to collect information on the behavioral interactions of Sierra bighorn, deer, and predators to gain a complete understanding of the dynamics in this important ecological community.

In addition to monitoring predation events, we are also able to greatly increase the overall knowledge of mountain lion biology, and to contribute to the statewide mountain lion monitoring project.

Mountain Lion Monitoring

Adult mountain lion

Adult mountain lion

Mountain lion kittens in den.

Mountain lion kittens in den.

Bobcat on deer kill

Bobcat on deer kill

Mountain lion track

Mountain lion track

During 1991-2011, we captured, collared, and monitored 130 individual lions that used Sierra bighorn habitat. New advances in technology allowed more intensive monitoring via GPS collars that provide more accurate data at a higher frequency than the traditional VHF collars. GPS collars were used to identify clusters of locations that indicate kill sites, which were investigated to determine the prey species. These collars allowed recovery program personnel to identify individual mountain lions that posed a threat, quantify predation rates, and determine whether predation was limiting the recovery of Sierra bighorn. They also allowed personnel to learn more about the natural history of mountain lions in the eastern Sierra, such as their home range sizes and mortality causes.

During 2012-2015 lion monitoring efforts were largely discontinued, but in the fall of 2017 lion monitoring efforts resumed in earnest. During 2023, we documented a minimum of 55 lions in the eastern Sierra lion population. This was the greatest number of individual lions counted since the lion monitoring program for Sierra bighorn began.

Removing lions that are a legitimate threat to the recovery of Sierra bighorn is efficient and effective protection for the bighorn. Between 1999-2012, we documented a minimum of 71 Sierra bighorn killed by lion predation. We documented a minimum of 42 Sierra bighorn killed by lions in 2022. See recent research from this project: Predation impedes recovery of Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep (PDF).

About Mountain Lions

The names cougar, puma, panther, and catamount all refer to the same animal, the mountain lion (Puma concolor). The scientific name reflects the solid tawny color of the mountain lion along its upper body. The belly is white and there are black markings at the base of the whiskers, the backs of the ears, and the tip of the tail.

Young mountain lions are born with spots that fade by six months of age. Mountain lions are sexually dimorphic (there is a physical difference between males and females). Adult females in the eastern Sierra average 88 lbs (40 kg), while adult males average 128 lbs (58 kg). Despite this, it can be difficult to tell a male and female apart unless the animals are in hand.

Juvenile mountain lions will remain with their mother (adult males do not participate with offspring) until they are 18-24 months old, at which point they will generally disperse, sometimes substantial distances, and establish their own home ranges. In the eastern Sierra, adult female home ranges average 39 mi2 (100 km2) and adult male home ranges are typically 2-3 times larger. Beginning around 3 years of age, females will produce litters of 2-4 cubs every 2 years. A female may produce upwards of a dozen offspring in her lifetime.

Mountain lions are obligate carnivores, meaning they must kill prey to survive. In the eastern Sierra, mule deer comprise the vast majority of prey, although many other species are consumed as well, such as other ungulates (e.g., tule elk, Sierra bighorn), smaller predators (e.g., bobcats and coyotes), lagomorphs (cottontails and jackrabbits), rodents, and birds. Mountain lions may occasionally kill livestock and domestic pets, but this can be mitigated through husbandry practices.

Some mountain lion populations in southern California have experienced substantial habitat fragmentation and are vulnerable to the effects of inbreeding. However, recent genetic work indicates that the eastern Sierra lion population, along with populations in the western Sierra Nevada and north coast, are large, genetically diverse, and well connected with each other (Gustafson et al. 2019).

Mountain Lion Observations

Predator monitoring personnel with the Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Recovery Program investigate mountain lion sightings reported by the public, many of which turn out to be cases of mistaken identity. Bobcats in particular are often mistaken for mountain lions, but bobcats in the eastern Sierra rarely exceed 35 lbs (16 kg), generally have numerous markings about the body, and have a much shorter tail than mountain lions. Reports of livestock depredation assumed to have been caused by mountain lions are also often mistaken; other predators such as bobcats, coyotes, foxes, and even feral dogs may be responsible.

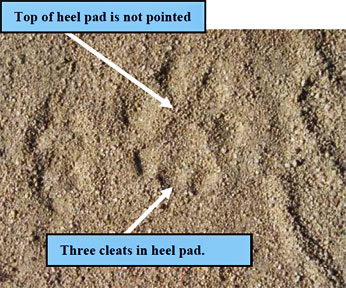

Mountain lion tracks are frequently misidentified, being especially confused with canine (i.e., dog, coyote) tracks. However feline tracks (i.e., mountain lions and bobcats) have unique features in the heel pad that distinguish them from canine tracks. The base of the heel pad in feline tracks have three cleats and the top is flat, whereas usually canine tracks only have 2 lobes at the base of the heel pad and the top is more angular. Very rarely a dog may have a similar track, in which case the presence of claw marks and other factors may eliminate it as a cat track. Size is not useful in distinguishing mountain lion tracks from domestic dog tracks, but it is useful for distinguishing mountain lion from bobcat tracks, which are much smaller.

Black mountain lions are occasionally reported, but in the history of mountain lion hunting, which includes hundreds of thousands of specimens from North and South America dating back for over a century, a black mountain lion has never been definitively observed. The black panthers seen in movies are either black jaguars or black leopards, both species which can commonly produce melanistic (black) offspring.