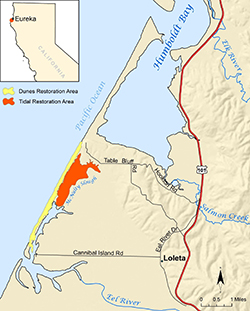

Restoration project area. CDFW photo by Andrew Hughan.

Yellow and orange indicate restoration areas at the Ocean Ranch Unit of CDFW's Eel River Wildlife Area.

How does one best go about making an already bountiful and bucolic part of the Golden State even better? Sometimes, perhaps paradoxically, it pays to look to the past in order to be forward thinking in the present.

CDFW, Ducks Unlimited, and many partners have undertaken the Ocean Ranch Unit of the Eel River Wildlife Area Integrative Ecosystem Restoration Project Planning Process to enhance the estuarine and coastal dune ecosystem of the Ocean Ranch Unit in Humboldt County

The approximately 2,600-acre Eel River Wildlife Area was acquired to protect and enhance coastal wetland habitat, and was designated as a wildlife area by the California Fish and Game Commission in 1968. The initial decision to undertake an estuary restoration-planning project began more than a decade ago. After several years of monitoring to gather necessary data, Ducks Unlimited completed a feasibility study, funded by CDFW’s Fisheries Restoration Grant Program and the California State Coastal Conservancy, in December 2015.

The primary goal is to restore and expand natural estuarine and dune ecosystem functions, including the recovery and enhancement of native species (including fish, invertebrates, wildlife and plants) and their habitats. These changes should also help mitigate current and future impacts of climate change. Sea level rise will likely result in saltwater inundation further upstream, which is expected to modify habitats (for example, the loss of tidal marsh migration inland) and the size and shape of the estuary.

The project has been a revelation for Michelle Gilroy, a CDFW district fisheries biologist who works primarily in Humboldt and Del Norte counties.

“For the first time in my 30-year fisheries career, which began in the Eel River watershed, I am achieving a long-time goal of mine: To envision, develop and work through to completion, or near completion, a large restoration project,” said Gilroy. “This exciting project and the extraordinary team I am so very fortunate to work with is making that dream a reality – and in the Eel River estuary, one of California’s largest estuaries. It is definitely one of the highlights of my career.”

Improving the connectivity of tidal and freshwater habitats, and controlling or eradicating invasive plants, are key goals of the restoration project.

A feasibility study guiding the project analyzed the potential for expanding tidal functions within 475 of the 933 acres of the unit to aide in the recovery and enhancement of estuarine habitat and native species. Restoration of these essential habitats is vital to the recovery of anadromous salmonid populations in the Eel River, as estuaries provide critical nursery and rearing conditions for juveniles prior to ocean entry.

The unit is located within the Eel River estuary, a mile and a half north of the mouth of the Eel River and approximately four miles northwest of Loleta. The unit is comprised of a diverse set of habitats, including coastal dunes, riparian woodlands, tidal mudflats, tidal slough channels, salt marshes and managed freshwater marshes.

Prior to second-wave human settlements, this portion of the estuary, then inhabited by Native Americans, consisted primarily of salt-marsh habitat dotted with areas of spruce and hardwood forest, and native grasslands. An abundant fishery, which included the prized salmon, along with native plants, provided sustenance for the Wiyot people who lived around Humboldt Bay and the estuary. As Euro-Americans settled this region, however, they largely drove the Wiyot people off their traditional lands and began to repurpose portions of the environment.

By the end of the 1800s, most of the salt marsh and forestlands were drained and converted to farm and grazing land. This conversion of tidal marshes to pastures was done with purpose – but such perceived progress carried an ecological cost.

The construction of levees and tide gates to drain salt marsh increased sedimentation, flooding, and the amount and diversity of habitat and food supply for fish and wildlife declined throughout the estuary. This degraded the prior functioning, highly productive estuary ecosystem. In addition, invasive species now threaten the diversity or abundance of native species through competition for resources, predation, parasitism, interbreeding with native populations, transmitting diseases, or causing physical or chemical changes to the invaded habitat.

Despite these declines, the Eel River delta, which includes the Eel River Wildlife Area, today continues to provide vital habitat for many aquatic and terrestrial organisms, including state and federally threatened and endangered fish, wildlife and plant species, and many state species of special concern. More than 40 species of mammals and 200 species of birds use the delta area and researchers have documented at least 45 fish species in the Eel River estuary alone.

The area provides essential spawning, nursery and feeding grounds to several commercially and recreationally important species, including Dungeness crab. Estuaries are among the most productive and diverse ecosystems in the world and are one of the preferred habitats for young Dungeness crabs.

Dungeness crabs use estuaries as critical nursery habitat in their juvenile stages, as not only a refuge from predation – particularly in estuaries with structural habitat such as eelgrass – but also because of the abundance and diversity of prey provided by estuaries. Dungeness crabs are opportunistic feeders – clams, fish, isopods and amphipods are their preferred food sources, as well as other Dungeness crabs. Their predators include those larger crabs, octopuses, and fish, including salmon, lingcod and various rockfishes.

Wildlife, of course, is not the only form of life to reap the benefits of this region, as humans enjoy a range of outdoor activities, including fishing, bird-watching, boating, hiking and hunting.

The project is expected to begin in the summer of 2019.

CDFW photos and map

Top photo: CDFW Senior Environmental Scientist Kirsten Ramey and Eric Ojerholm of the Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission.

Partners, Funding and Staff

Ducks Unlimited, in partnership with CDFW staff, has recently secured project planning funds from the California Wildlife Conservation Board, and initial project implementation funds from the NOAA Restoration Center. To complete the restoration design and environmental compliance process, this second phase of restoration planning will consist of a continued CDFW and Ducks Unlimited partnership, with additional assistance from several local consultants and a Technical Advisory Committee (TAC). The TAC includes representatives from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, National Marine Fisheries Service, California Coastal Commission, California State Coastal Conservancy, North Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board, California Sea Grant, California Trout, Humboldt County Resource Conservation District, Humboldt State University, Redwood Region Audubon Society, private landowners, and the Wiyot Tribe. Additional project partners include AmeriCorps, Tom Origer and Associates, Pacific Coast Fish, Wildlife and Wetlands Restoration Association, GHD Inc., H.T. Harvey and Associates, Moffatt and Nichol, Northern Hydrology Engineering, Pacific Coast Joint Venture, and the Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission.

CDFW staff who have served on the project management team include Michelle Gilroy, Allan Renger, Scott Monday, Kirsten Ramey, James Ray, Mark Smelser, Gordon Leppig, Michael van Hattem, Jennifer Olson, Linda Miller, Clare Golec, Charles Bartolotta, Robert Sullivan, Tony LaBanca, Mark Wheetley, Scott Downie, Adam Frimodig, Jeff Dayton, Mike Wallace, Vicki Frey, John Mello, and Karen Kovacs.