Regina working as a student assistant at the Pesticide Investigations Unit. © Regina Donohoe, all rights reserved.

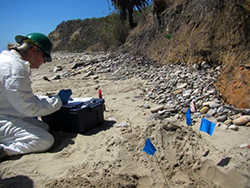

Regina collects grunion eggs at El Capitan State Beach after a major Santa Barbara oil spill. © Regina Donohoe, all rights reserved.

Crew sampling in Tyvek suits following the Santa Barbara oil spill. © Regina Donohoe, all rights reserved.

Regina Donohoe is an OSPR staff toxicologist working in the Resource Restoration Program. As an ecotoxicologist, she combines the methods of ecology and toxicology to evaluate the effects of pollutants on fish, wildlife and their habitats.

For the past 17 years, Regina has been involved in the remediation of hazardous waste sites, petroleum production facilities and military bases to ensure that chemical contamination is cleaned up to levels that are protective of our natural resources. Regina also provides ecotoxicology support for spill response and assesses the injuries resulting from spills as part of the natural resource damage assessment team.

Regina received a Ph.D. in toxicology from Oregon State University, a M.S. in ecology from San Diego State University and a B.S. in environmental toxicology from the University of California at Davis.

Who or what inspired you to become a scientist?

One summer day when I was a bored five-year-old, my mom asked me to roam our foothills property and bring back every different kind of leaf I could find. It was a clever mom move to keep me busy all afternoon but it is my earliest memory of being fascinated with nature. However, it wasn’t until I met my high school biology teacher that I knew I wanted to be a scientist. Her classroom was a museum filled with skeletons, shells, plants and aquaria of fish, and that class set me on the path to major in science in college. Later, my graduate school advisors shared their passion for science and kept me going.

What got you interested in working with fish and wildlife?

While trying to decide on an undergraduate major, I took an introduction to environmental toxicology class. The professor told the grisly story of the dancing cats of Minimata Bay, Japan during the 1950s. After mercury-laden wastewater was released into the Bay, the fish accumulated it and when the cats ate the fish, they began to walk erratically (or “dance”) because the mercury poisoned their nervous system. It was an “aha” moment. The fact that a single chemical could disrupt an entire ecosystem intrigued and saddened me at the same time, inspiring me to declare environmental toxicology as my major and the focus of my career.

What brought you to CDFW? What inspires you to stay?

It was 1982 when I took a year-long Student Assistant job at the Pesticide Investigation Unit Laboratory of the then-California Department of Fish and Game. The job duties included “creamer patrol,” picking up dead carp from agricultural drains in the Sacramento Valley for pesticide analysis. On a 100° F day, the fish decayed so quickly that when they were scooped up in the net they often exploded into a creamy mess. Another aspect of the job was to conduct bioassays with fish to determine what levels of pesticides in the water were safe. I left the position to study the effects of sewage discharges on the algal populations of Tijuana estuary, meeting my husband while knee-deep in mud. After that, I researched how chemicals could act like hormones, with environmental estrogens altering reproduction in fish. This led to an ecotoxicologist job at the California Environmental Protection Agency. A friend recommended I apply for a job at OSPR and 17 years later, I returned to where I had started.

What is a typical day like for you at work?

My work moves in a couple of different gears. On the slower gear, a ten-year timeframe, I work on remediation of military bases and hazardous waste sites. For each site, the nature and extent of chemical contamination is characterized, the method and level of cleanup is decided, cleanup occurs and then there is follow-up monitoring. For example, we have removed lead bullets from sand dune firing ranges, metal plating waste from salt marshes and crude oil from grasslands. Throughout the multi-year process for each site, I make many visits, read reports, attend meetings and provide comments related to ecotoxicology.

When spills happen, everything shifts into high gear. I pull together information about the spill, plan and conduct studies and assist wherever help is needed. After the spill response ends, the natural resource damage assessment process continues but at a less frenetic pace. I analyze data, prepare presentations and write up results.

In between, I am involved in training and planning, teaching classes on the effects of oil on ecosystems and reviewing literature to be better prepared for the next spill.

Over the course of your career, was there a discovery or an incident that surprised you?

When we were called to respond to the oil spill in Santa Barbara in 2015, we had to plan for fish sampling one day and carry it out the following day. Usually, it might take a couple of weeks to organize such a sampling event. But people from multiple agencies volunteered their gear and help, others quickly purchased needed supplies, experts flew in to collect tissue samples and folks drove many miles to be there on short notice. The sampling day began early, including gearing up in bulky protective clothing to fish on the beach, and ended with a late night of data intake. Everyone brought a positive attitude and worked hard to get the samples we needed to support the natural resource damage assessment. We achieved a near-impossible task because everyone gave it their all. The power of people working together truly surprised and amazed me.

What do you enjoy most about working in ecotoxicology?

California has incredibly diverse ecosystems – deserts, grasslands, chaparral, forests, rivers, wetlands, estuaries and marine habitat. Spills happen all over California, providing me opportunities to investigate impacts to many plant and animal species in a wide variety of habitats and spill scenarios. For example, I’ve been asked: How does diesel affect an old growth redwood tree? What levels of metals are of concern to California Tiger Salamanders? Is brine harmful to ephemeral streams? How does crude oil impact kelp forests? These questions make me scratch my head and think, and learn new things every day. That, to me, is the best thing about being a scientist.

If you had free reign and unlimited funding, what scientific project would you most like to do?

When scientists began to evaluate how oil spills affected ecosystems in the 1970s, they did some interesting laboratory and field studies, but they were limited by the analytical chemistry and assessment methods available at the time. In many cases, oil concentrations in water or tissues were not measured or were simply quantified as total hydrocarbons. Today, we know that oil is a mixture of hundreds to thousands of chemicals that we can quantify at very low levels in the environment. We also have new biochemical and genetic tools that can detect subtle changes in animals in response to oil exposure. It would be great to repeat many of those earlier studies using our current technologies to further our understanding of how oil affects ecosystems, improving our ability to respond to spills and restore habitats following spills.

Do you have any advice for people considering careers in science or natural resources?

Follow that innate scent trail. What makes work seem like play? What keeps you going when you lose the trail? What rewards you at the end of the day? If you have a passion for science or the natural resources, make it your career and be sure to stop and smell all those interesting scents along the way.

Photo © Regina Donohoe, all rights reserved

Top photo: Regina, conducting rocky intertidal monitoring on San Francisco Bay