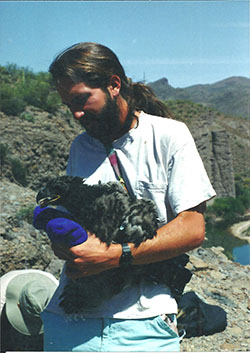

1994, Henkel performing work with Bald Eagles

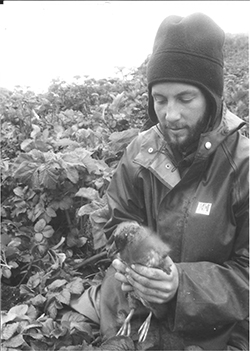

1995, Henkel performing work with Tufted Puffins

2010, Henkel performing research on Western Grebes

2010, Henkel works on Rhinoceros Auklet restoration project

Laird Henkel is a senior environmental scientist-supervisor with CDFW’s Office of Spill Prevention and Response (OSPR), where he serves as director of the department’s Marine Wildlife Veterinary Care and Research Center (MWVCRC) in Santa Cruz. Laird joined OSPR in 2007 as the statewide oiled wildlife response coordinator. He moved to his current job in 2010. The MWVCRC is the primary care facility for oiled sea otters and serves as a center for research on the health and pathology of sea otters and marine birds.

Laird grew up in Connecticut and moved to California to attend UC Santa Cruz, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in biology. He subsequently earned a master’s degree in marine science at Moss Landing Marine Labs, where he studied the spatial distribution of marine birds on Monterey Bay. Prior to working for CDFW, Laird worked on a variety of research projects with birds including marbled murrelets and snowy plovers.

Who or what inspired you to become a scientist?

I’ve always been inquisitive, and enjoyed science books as a kid. I also spent quite of bit of time with other kids checking out critters living under rocks, and – probably like most kids – thought Jacques Cousteau (a famous marine explorer in the 70s and 80s) was awesome. But when I left for UC Santa Cruz, I was not necessarily planning on studying science. A variety of factors led me to major in biology and once I was in, I was hooked.

What got you interested in working with wildlife?

In college, I took some great natural history classes, including one working with elephant seals at Año Nuevo State Reserve, and an ornithology class, which led me to become fascinated with the lives of animals. The summer before my senior year, I assisted on a project assessing mountain goat behavior related to population size in Idaho, and right after graduating I had a great volunteer job working on a remote island in Alaska monitoring diet and growth of tufted puffins. Field biology was fascinating and a great way to see some amazing places, from Alaska to Maine to Costa Rica.

Who or what brought you to CDFW? What inspires you to stay?

I first worked for CDFW as a scientific aid for Senior Environmental Scientist Rob Titus in 1995, working with winter-run Chinook salmon. That was a short-term position. Then I moved back to Santa Cruz and had a variety of other field jobs with birds, earned a master’s degree in marine science, and worked at an environmental consulting firm for several years. One of my other jobs included conducting aerial surveys for marine birds and mammals under a contract with OSPR. Through that work, OSPR seemed like a great place to work and was in the right place at the right time when my current dream job opened up. I feel lucky to have it. I am inspired to stay because of the great work we do!

What is a typical day like for you at work?

I typically deal with various logistical issues—I’m responsible for my staff and for a complicated (and aging) facility. The facility is set up for oiled wildlife response including pools plumbed with seawater and a state-of-the-art necropsy facility (necropsies are the equivalent of autopsies but on non-human animals—here mostly sea otters and seabirds, but we’ve had an occasional great white shark or leatherback sea turtle). But all this logistical work can be rewarding. Planning projects and providing strategic vision for staff allows our team to respond effectively to oil spills, and allows my staff to work on exciting scientific work investigating health of sea otters and seabirds.

What is the most rewarding project that you’ve worked on for CDFW?

Our primary role at OSPR is response to oil spills and although we never look forward to them, the experience can be rewarding (albeit stressful). Spill response allows an opportunity to put our training to use and have a positive influence, hopefully making a bad situation better. My first big spill response was the Cosco Busan incident in the San Francisco Bay in 2007, only a month after I started. That was a great learning experience for me. Since then there have only been a few spills affecting substantial numbers of animals, most recently the Refugio spill in Santa Barbara in 2015. All of this work on oil spills is rewarding, especially to see cleaned and rehabilitated wildlife released back into the wild.

If you had free rein and unlimited funding, what scientific project would you most like to do?

There are many projects that would be intellectually stimulating and fun, and also a lot of conservation projects in desperate need of funding. But I think one way to have a big influence on recovery of threatened species would be to put more funding into investigating ways to minimize the impacts of corvids (ravens, crows and jays) on threatened species. Through our work on oil spill restoration projects, I’ve seen corvid impacts (corvids eating eggs or young of threatened species) as a common theme limiting recovery of multiple species. Corvids are very smart birds and they’ve done a great job of adapting to and benefiting from humans. Because humans are responsible for huge population increases in corvids, it would be great if we could do something to minimize their impacts on other species. But this is not an easy issue to address – thus the need for more funding.

What is the best thing about being a wildlife scientist?

Discovery. There will always be new things to discover, and that is the whole point of science.

The world of science and managing natural resources is often confusing or mysterious for the average person. What is it about the work you do that you’d most like us to know?

The natural world is indeed so mysterious! But I guess one thing for non-scientists would be not to let numbers and mathematical formulas scare you. Ecology as a science has become more mathematical over the years, and even we scientists have a hard time keeping up with new statistical methods and fancy mathematical models. Scientific studies should still be done in a way that makes sense – if you can see past the formulas and understand how a study or an experiment was set up, it is usually not too difficult to understand the results.

Is there a preconception about scientists you would like to dispel?

I think one misconception might be that scientists have all the answers. Any good scientist will tell you there is still a lot to learn, and the better you are at science, the more likely you are to acknowledge that we are not sure about a lot of things. Uncertainty is a big part of science, and properly assessing that uncertainty is important. (To be clear: global climate change is NOT something with a lot of uncertainty).

Any advice for people considering careers in science or natural resources?

Be curious and have an open mind. Science is all about not having pre-conceived biases, and being willing to accept findings that may be surprising or even in conflict with previously-held beliefs.

Photos courtesy of Laird Henkel. Top Photo: In 2010, Laird Henkel participated in the Deepwater spill response.