Purple urchins grazing a desolate kelp forest, Fort Ross, 2015. (Photo credit: A. Weltz)

Purple urchins consuming bull kelp fronds and stipes and crowding out native red urchins and abalone.

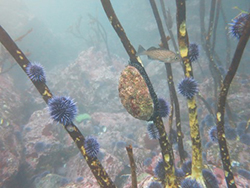

Unusual photo of abalone and purple urchins consuming bull kelp stipes. (Photo credit: A. Maguire)

Large aggregations of purple urchins are wiping out kelp forests, creating pink barrens and out-competing other species, such as abalone, for food. (Photo credit: A. Maguire)

Aftermath of the harmful algal bloom: dead abalone and other invertebrates washed up on shore at Fort Ross in 2011. (Photo by N. Buck)

Shrunken abalone due to lack of food, October 2015. The foot (meat) of the abalone should be roughly the same size as its shell. (Photo credit: S. Holmes)

The view of northern California’s beautiful coastline has historically been pristine and breathtaking. With dense kelp forest canopies blanketing the surface of the nearshore areas and protecting the abundant rockfishes, red abalone, sea stars and red urchins that lived below, it was a healthy, natural ecosystem rich with thriving inhabitants. Unfortunately, the ocean is now changing, and this idyllic scene is no more. But California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) marine scientists, citizen scientists and grassroots groups are all coming together to help turn back time.Their immediate focus is to eradicate the ever-increasing purple urchins.

For thousands of years, canopies of thick bull kelp (Nereocytis luetkeana) could be found along the coast of northern California, creating a rich subtidal home for the many fishes and invertebrates that lived and thrived in this region of the state. Today, bull kelp forests should be the foundation of our nearshore coastal ecosystem. The floating canopy of this brown algae gives shelter to young fish and sea stars, and the kelp itself provides food for valuable species, such as red abalone and red sea urchin.

Unfortunately, with the warming and changing ocean conditions in the last few years, scientists have noticed an alarming decline in these once prolific kelp forests. Though annually variable, in the just past five years, California’s kelp forests have declined by 93%.

In 2013, a mysterious wasting disease wiped out a large portion of the local sea stars in northern and central California. As a result, purple urchin populations exploded in the absence of the sea star, their main predator.

By 2014, a large patch of warm water developed off the coast, creating a catalyst that has further changed this underwater environment. The persistent warmer sea temperatures stress the kelp forests to the point that growth and reproduction have slowed dramatically and caused damage to remaining fronds and tissue.

But perhaps the most critical effect is that the purple urchin populations now thrive without their primary predators, and are left to graze the kelp unchecked. Purple urchins feed mostly on algae (like bull kelp) with beaks so strong that they can chew on everything from barnacles to calcified algae.

Along the north coast, purple urchins are now successfully outcompeting red urchins and abalone. The purple urchin population is now 60 times higher than normal. The areas that are now overrun by sea urchins with hardly any kelp left are referred to as “urchin barrens,” a type of ecosystem largely devoid of the biodiversity that used to flourish there. Due to this abrupt change, the seafloor now looks more like an underwater desert dominated by sea urchins, with little else alive.

“To address the impacts of the massive marine heat wave and kelp deforestation on the north coast we are going to need to shift our priorities and resources and come up with creative solutions,” says Dr. Laura Rogers-Bennett, a CDFW senior environmental scientist specialist based out of the Bodega Bay field office in Sonoma County. “I am encouraged that so many people and organizations are coming together in the Kelp Ecosystem and Landscape Partnership for Research on Resilience (KELPRR) collaborative and the "Help the Kelp" Campaign to promote kelp restoration in support of our kelp forest ecosystems and the human communities that make their living from the ocean.”

These negative effects reach from the ocean to the shore. Red abalone have been severely impacted by the loss of kelp and thus lack of food, causing the abalone fishery to close until at least 2021. Sea birds and marine mammals are also feeling the effects. With fewer fish available, the birds do not have enough food to feed their chicks. Reports indicate that 80% of black oystercatcher chicks and 90% of the local cormorant chicks are failing to survive. Harbor seals and sea lions are also hungry and feeling the effects.

In an all-out effort to address this devastating ecosystem change, scientists, management agencies and citizen scientists are all joining together to do everything they can to help. Their strategy is to harvest the purple sea urchins by hand to remove them from invading all of the substrate where bull kelp resides. By doing this they hope to create a network of healthy kelp patches along the coast.

Work is underway to create kelp refuge sites in North Caspar Bay, Noyo Harbor and Albion. This urchin removal project is a massive undertaking. Scientists hope also to try to develop commercial uses of the purple urchins, thus ensuring long-term sustainable harvesting.

Watermen's Alliance, a union of spearfishing clubs throughout the state, is coordinating urchin removal events this summer along the Sonoma and Mendocino coast using recreational divers wishing to assist with the purple sea urchin removals.

Next up will be the July 27-28 Purple Urchin Removal Event on Noyo Beach in Fort Bragg. They will need as many free divers and scuba divers as possible to participate, as well as kayakers to ferry full collection bags from the divers to boats and empty bags back to the divers. Just bring your dive gear or kayak gear and a valid California fishing license if you will be a diver removing urchins.

If you dive, boat, kayak or are just interested in helping, please contact the Noyo Center for Marine Science or Josh Russo with Waterman’s Alliance at (707) 333-9575 for details.

For more information about how to get involved, and stay up to date on kelp recovery efforts, please visit the following links. There are many opportunities for involvement, whether you are a scuba diver, freediver or just a concerned community member!

- ReefcheckCA - volunteer to help monitor coastal ecosystems

- “Help the Kelp” Program - Noyo Center for Marine Science

- Watermen’s Alliance - advocates for clean, productive and sustainable fisheries.

- Urchinomics: Focused on development of a commercial market for the purple urchin

Please join us for the next installment of the Conservation Lecture Series, “The Perfect Storm: Multiple Climate Stressors Push Kelp Forest Beyond Tipping Point in Northern California” by Dr. Laura Rogers-Bennett on Thursday, July 18 from 1:00 – 2:30 p.m. Dr. Rogers-Bennett will talk about the catastrophic decline of the kelp forests and the ecosystem it supports, including the red abalone and sea urchin fisheries, and the effects of climate stressors on northern California kelp forests. Register at www.wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Lectures.

This lecture will be held by webcast only. Members of the public can sign up using this registration link. For more information, please contact Whitney.Albright@wildlife.ca.gov or visit the Conservation Lecture Series website.

CDFW Photos. Top Photo: Unusual foraging behavior near Elk in Mendocino County: a large red abalone climbing a bare kelp stalk trying to reach fronds that are not there. (K. Joe)

Media Contact:

Carrie Wilson, (831) 649-7191