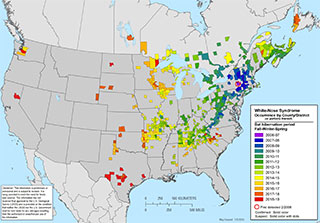

Map showing extent of WNS occurrences in North America. (click/tap to enlarge)

Map showing extent of WNS occurrences in North America. (click/tap to enlarge)

Bat with visible growth of Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd) fungus on muzzle and ears. USFWS Photo.

Bat with visible growth of Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd) fungus on muzzle and ears. USFWS Photo.

White-nose syndrome (WNS) is a disease caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd). The disease is estimated to have killed more than six million bats in the eastern United States since 2006 and can kill up to 100% of bats in a colony during hibernation. Until recently, the disease had been spreading slowly in eastern North America from its point of origin in upstate New York. However, in March 2016 a case of WNS was confirmed in a little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) in Washington near North Bend (30 miles east of Seattle). This is a jump of about 1,300 miles from the previous western-most known occurrence of the disease in Nebraska and Minnesota. WNS has continued to spread in Washington State since 2016.

In July 2019, CDFW and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) announced surveillance results suggesting the fungus that causes WNS is now present in California. As part of a national surveillance program for WNS and Pd, swab samples have been taken from Myotis bats at sites around the northern part of California. In 2018, a single sample from a bat in the town of Chester had a low-level detection of the fungal DNA, and in 2019, three bats sampled in Chester had positive, though low-level, results for the fungal DNA. In 2023, for the first time, two Myotis bats from Humboldt County tested unambiguously positive for the Pd fungus, and 11 bats from throughout the state returned low-level positive results. See CDFW's 2023 WNS Surveillance Summary Report (PDF) for more details. At this time, there is no indication the disease itself has taken hold in California bat populations. However, surveillance results like these elsewhere in the country have preceded WNS occurrence by one to a few years.

The fungus grows on and in the skin of bats during winter hibernation, in some cases giving them a white, fuzzy appearance on the muzzle, wings and ears. The fungus invades deep skin tissues and causes extensive damage. Affected bats arouse more often during hibernation causing them to burn up fat reserves needed to sustain them through winter, leading to starvation and death. Wing damage may also cause problems with physiological processes such as blood circulation, thermoregulation, water balance, and gas exchange. Impairment of any or all these processes may also lead to death.

Report a Sick or Dead Bat

WNS Key Findings

- White-nose syndrome causes very high mortality (up to 100%) in bat colonies during hibernation.

- The pathogen responsible for the disease is Pseudogymnoascus destructans (formerly Geomyces destructans).

- Bat-to-bat and infected environment-to-bat contact appear to be the primary transmission routes, although the fungus can also be carried on clothing and equipment to new locations and thereby spread the disease.

- The fungus and disease have been spreading across North America towards the West and into Canada. A new occurrence of WNS in the state of Washington was discovered in March 2016.

- Many species of bats in California are potentially susceptible; currently seven species are known to be affected.