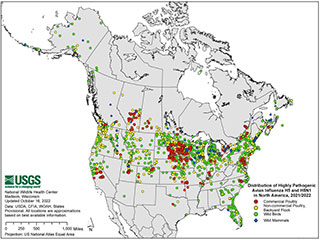

Map: Distribution of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5 and H5N1. (click/tap to enlarge)

Map: Distribution of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5 and H5N1. (click/tap to enlarge)

Avian influenza is an infectious disease of birds caused by type A influenza viruses. These viruses naturally circulate among waterfowl and other waterbirds. Viruses are classified based on two surface proteins, Hemagglutinin (H) and Neuraminidase (N), which combine to form different subtypes (e.g., H5N1, H5N2, H7N3). Virus subtypes can be further broken down into different strains which generally circulate within a migratory flyway or geographic area. Signs of infection in wild birds may range from none to severe, and is in part, dependent upon the species of wild bird and virus subtype and strain. Avian influenza viruses are further classified as highly pathogenic (HP) or low pathogenic (LP) based on their ability to cause disease in domestic poultry. Historically, viruses of H5 and H7 subtypes have been more likely to become highly pathogenic.

In December 2021, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 of Eurasian-lineage was detected in domestic poultry and wild birds along the Atlantic coast of Canada. In January and February 2022, detections were made for the first time in wild birds and domestic poultry in the eastern United States. Following its initial detection, the virus has spread to nearly every state with numerous detections in both domestic poultry and wild birds. Prior to its detection along the Atlantic coast, Eurasian HPAI H5N1 activity had been on the rise across Europe in domestic poultry and wild birds since October 2021. In the U.S., detections have been made during surveillance in apparently healthy hunter-harvested and live-sampled waterfowl, as well as in sick and dead waterfowl and other wild birds found individually or during mortality events. Although avian influenza viruses naturally circulate among waterbirds, the strain of H5N1 currently in circulation in the U.S. and Canada has been causing illness and death in a higher diversity of wild bird species than during previous avian influenza outbreaks. The virus also remains highly contagious for domestic poultry. Avian predators and scavengers may be exposed to avian influenza viruses when feeding on infected waterfowl or foraging in areas heavy contaminated with virus shed by waterfowl. Infection with avian influenza viruses among songbirds, including many common backyard birds, appears to be relatively uncommon but more study is needed.

The Wildlife Health Lab in coordination with regional staff and other partners are monitoring wild bird populations for signs of illness. The Wildlife Health Lab continues to investigate mortality events, especially those involving 5 or more wild birds, and conduct surveillance testing for avian influenza. Additionally, CDFW supports the national HPAI surveillance plan for avian influenza testing in hunter-harvested waterfowl and live-birds led by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. For more information please see CDFW's HPAI Information Sheet (PDF).

Report a Dead Bird