Vicky Monroe is an environmental scientist with the Wildlife Management Branch in CDFW’s Central Region. Based in Bakersfield, she is the unit wildlife biologist for Kern County. Her work has included resource assessment surveys of deer, elk, pronghorn, upland game birds and San Joaquin kit foxes by vehicle, fixed-wing airplane and helicopter. She has captured black bears, elk and kit foxes and assisted with deer captures. Other critical aspects of her work include addressing the human-dimensions of wildlife management and wildlife conflicts, providing technical expertise and assistance and educating the public.

Vicky earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Psychology with an emphasis in Animal Behavior and a Minor in Biology from Colorado State University. She also earned a Master’s degree in Zoology from James Cook University in Queensland, Australia and is currently pursuing a graduate certificate in Environmental Conflict Resolution and Collaboration from George Mason University in Virginia.

What is a typical day like for you at work?

That depends on the time of year. During the spring, summer and fall, I have a steadily increasing volume of resource assessments, wildlife conflicts, phone calls, emails, meetings, office work, field responses, and sometimes extensive travel throughout the county. Kern County, at 8,100 square miles, is larger than many states. When I am in the field, the diversity of calls that I may respond to never ceases to amaze and thrill me.

In one week in my first year, I provided field responses from the Mojave to Maricopa, agricultural to oil fields, and throughout the Sierra Nevada and Transverse mountain ranges. I responded to calls regarding an injured condor, human-black bear conflicts, mountain lion depredation, urban kit foxes and desert tortoises, and conducted an elk calf capture. I also work closely with our wildlife officers, Natural Resources Volunteer Program participants, non-governmental organizations and local, state and federal government staff.

My relative slow season lasts about two to three months each winter. During that time I respond to emails and phone calls from the public, work to better organize file documents and reports and update data files. It is a good time to strategically assess wildlife management and conservation priorities, provide outreach to stakeholders and maintain and strengthen working relationships.

What is the most rewarding project that you’ve worked on for CDFW?

One of the most challenging, rewarding and unexpected “projects” that I’ve worked on for CDFW occurred my first year (2014) managing Kern County, and it was not so much a project as a call to action! Kern was experiencing an unprecedented increase in reported black bear activity, sightings, depredation and wildlife conflicts due in part to extreme drought. Some of us jokingly called it “Bearmageddon” and it certainly made for an intense year or two. Department wildlife officers and I captured and relocated numerous bears from Bakersfield and other areas. My two most unusual field responses were for multiple bears wandering into Bakersfield city limits in a single 12-hour period, and the night capture of a sow and cub stuck in a solar panel facility in Boron.

Providing increased public information, community outreach, media response and “Bear Aware” public meetings were a critical component of our strategy to mitigate human-wildlife conflicts and to educate and serve the public. CDFW’s Office of Communications, Education and Outreach staff was instrumental in supporting this effort. It was rewarding to collaborate so effectively to transform human-bear conflicts into an opportunity to empower residents with greater knowledge about wildlife, our department’s mission and values, responsible stewardship and co-existence.

What is most challenging about working with wildlife?

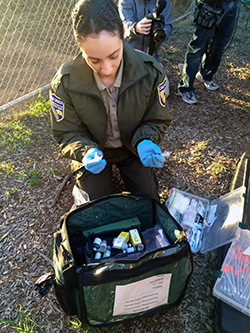

Probably the knowledge of the profound responsibility we have to each animal with which we come into contact. With each field response or capture effort, we become stewards of that individual animal. Its life is literally in our hands and it is difficult knowing that we cannot control every condition in the field. Whether capturing black bears in the desert, kit foxes in the city, elk in an enclosure or deer in the mountains, the focus, intensity and level of preparation remain the same. As biologists, we are armed with the expertise and experience to respond where others may not. That responsibility is not to be taken lightly. Another major challenge is balancing people’s expectations about when a field response, intervention or capture effort is necessary versus inappropriate.

What is the most challenging aspect of your career as an environmental scientist?

Trying “to do it all” in a 40-hour work week. As a unit wildlife biologist, I am on the front line and often in the public eye. It can be challenging to address everything that comes my way in the order and manner in which I would like to address things. Another challenging aspect is serving members of the public through education and outreach in a manner that empowers them to co-exist with wildlife, drives science-based management and conservation and balances the expectations people may have about how wildlife “should” act or behave.

If you had free reign and unlimited funding, what scientific project would you most like to do?

There are almost too many areas of scientific interest, management and conservation to narrow the scope. Kern County has the most diverse range of habitats of any county in the state; it is a remarkable place. I would love to conduct a study to assess genetics, disease, predation, fecundity (reproductive rates and success) and recruitment (fawn survival) of migratory and resident deer herds. I would love to conduct a study to assess genetics, survival, mortality and disease impacts on mountain lions and black bears. A study on the abundance, fecundity, and mortality of lesser studied species or species of special concern in Kern, such as fishers, would also be valuable. In particular, conducting a study to further assess genetics, disease impacts and mortality of the urban kit fox population in Bakersfield would be incredible. Really, I would love to do it all… I guess I would need a whole stable of research scientists on my team!

Any advice for people considering careers in science or natural resources?

Be bold, be serious, be focused, and never lose faith that you can end up exactly where you were meant to be with a career in science or natural resources. Serving as a professional scientist (such as a wildlife biologist) is a true calling, and the path is not always direct or clear. Do not limit yourself -- be open to pursuing different opportunities and unique experiences and never stop trying to gain new skills, diversify your skill set and cultivate deeper expertise. Remember that a college degree is critical and an advanced degree is valuable, although not vital. And finally, taking initiative is non-negotiable. Do not be passive. Show a willingness to acquire experience (either paid or volunteer) as readily as you attain your education, rather than waiting to graduate with a degree and then hoping to find career-relevant work. Building a career is a lifetime process, a journey, and no one can start it for you except you.