Rocky Mountain elk in Modoc County taken during a CDFW survey in 2019.

Scientists at UC Davis analyzed scat to determine where the elk originated.

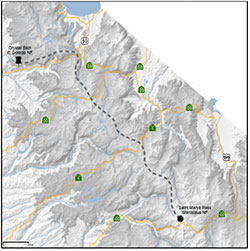

A map of the elk’s journey from Tahoe to Sonora Pass.

About a dozen years ago, California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) biologist Nathan Graveline heard rumors that a sole elk had been spotted in a highly unusual location – the Stanislaus National Forest, between the Clavey and Tuolumne rivers. At the time, scientists didn't have the technology to confirm the reports.

“Nobody knew where the elk came from. We weren't able to piece any of that together,” said Graveline.

Last September, scientists got word of another unexpected elk sighting, this time just south of Lake Tahoe in the Crystal Basin Recreation Area. “When I heard there was possibly an elk back in the area, I thought, ‘We’ve got to jump on this. If we can get a good DNA sample, we can figure out where the elk came from,’” said Graveline.

They set up trail cameras and were able to get a photograph of the elk. They also collected scat samples, which they sent to Dr. Benjamin Sacks, director of the Mammalian Ecology and Conservation Unit at the University of California, Davis’ Veterinary Genetics Lab. Through DNA analysis, Dr. Sacks and Ph.D. student Taylor Davis determined that the elk probably originated from a herd in the northeastern part of the state.

“We first estimated likelihoods of the observed genotype originating from each potential population based on the frequency of the alleles in those populations. We then obtained a probability or origin for each population by dividing its likelihood by the sum of all likelihoods for all populations,” said Dr. Sacks.

The report of an elk near Lake Tahoe was unusual in and of itself — but six weeks later the story got even more interesting. Scientists conducting a helicopter survey reported seeing a bull elk near Sonora Pass.

Scientists went to the location of the reported sighting and were able to collect scat samples, which they sent to Dr. Sacks’ lab for analysis.

“We did the genotyping and it turns out it was the exact same elk that was tracked south of Lake Tahoe,” said Tom Batter, a Ph.D. candidate in Dr. Sacks’ lab.

It appears scientists had on their hands a trailblazing elk — a Rocky Mountain elk that traveled 40 miles in six weeks and ended up farther south in the Sierra than had previously been reported.

“That boy was on quite a quest,” said Shelly Blair, a unit biologist in El Dorado County. “He likely traveled over some pretty rocky terrain, depending on which route he took. He probably had to cross over Interstate 80 or the 395 corridor at some point. Without the DNA, it would have been a total mystery as to where the elk came from.”

Kristin Denryter, coordinator of CDFW’s Elk and Pronghorn Antelope Program, said the bull’s journey is likely evidence of population growth among elk or herd densities that exceed the carrying capacity of the habitat.

“We know there’s great potential for expansion by bulls, and this means there could be recolonizations happening. We want our elk to be expanding and figuring out new habitats and going to new places. A bull elk like this might be figuring out new migratory routes and allowing for migration to persist. If he’s taking this route, then other elk and wildlife could be doing the same in the future,” said Denryter.

As to what motivated the bull elk to travel so far off the beaten path, Graveline says it may have been looking for a mate or new territory.

“He went farther south than he would need to for food, so I don’t think he was driven by that. This is a younger bull, and sometimes they get pushed out of a herd by a more mature bull,” he said.

Denryter added, “Younger males that are not competitive for mates are more likely to go off on their own or get pushed out of the herd. There’s absolutely a chance he could turn around and head back the way he came, but he’ll likely keep moving to find a mate.”

Although the elk is described by scientists as young, its exact age is unknown. Elk typically live 10-13 years in the wild. As far as threats in the wild – mountain lions hunt elk, but deer are their preferred prey. This elk’s biggest threat would likely be poaching, said Denryter.

Scientists are excited about the possibility that elk are expanding their range, but it’s also their job to prepare for corresponding conflicts.

“It’s kind of a double-edged sword,” said Denryter. “There’s risk of disease if elk come into contact with livestock while creating new migratory routes, and they can compete with livestock for forage. They can also cause vehicle accidents. Understanding the movements of elk and other wildlife is important so we can address these potential conflicts.”

CDFW would like help from the public in tracking the movements of elk populations statewide. Elk sightings can be reported online on the department’s website.

“If you see an elk — especially in places where you don’t normally see one — definitely take a photo with your smartphone and let us know,” said Denryter. “Smartphone photos are geotagged which will help us confirm the location. The online form allows you to upload photos and share any interesting observations. It’s really helpful to have this information so when there are conflicts or regulatory changes proposed we have data to help make informed decisions.”

CDFW Photos. Top Photo: A bull elk

###

Media Contact:

Ken Paglia, CDFW Communications, (916) 322-8958