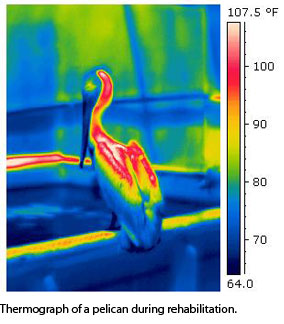

Thermograph of a pelican undergoing rehabilitation at International Bird Rescue. This image shows surface temperatures, with white/red indicating warm temperatures, and green/blue indicating cool temperatures.

Thermograph of a pelican undergoing rehabilitation at International Bird Rescue. This image shows surface temperatures, with white/red indicating warm temperatures, and green/blue indicating cool temperatures.

When MWVCRC staff members are not actively participating in an oil spill response, staff members pursue research projects aimed to help improve the care of oil-affected wildlife. Funded by an Oiled Wildlife Care Network (OWCN) research grant, researcher Hannah Nevins and others have been validating the use of thermography to assess body temperature and waterproofing of seabirds during rehabilitation.

Traditionally body temperature of seabirds is assessed by taking a cloacal temperature measurement. This method requires handling of the bird, which can induce stress, and is time consuming when multiple birds are in care. Similarly, traditional assessment of waterproofing in seabirds requires a handler to physically feel for wetness beneath the feathers, a process which is time consuming for handlers, stressful for birds, and requires physical re-alignment of feathers, which imposes additional energetic requirements. Thermographic assessment of these parameters has the potential to reduce handling time and stress.

Thermography is the use of a thermal camera to visualize surface temperatures. Traditional applications include firefighting (locating people in burning buildings), detection of electrical leaks, and assessing thermal insulation in buildings. More recently thermography also has been used for wound and injury assessment in captive and wild animals, and was even used to assess fur condition of sea otters after washing (see sea otter washing study)[link to tab 2 link 3]. To test the applicability of this technology in seabird rehabilitation, researchers worked with captive seabirds at the Monterey Bay Aquarium and wild seabirds undergoing rehabilitation at International Bird Rescue, two partner OWCN organizations.

Thermography also was useful in assessing waterproofing for seabirds undergoing rehabilitation. Assessing waterproofing is important because seabirds that are waterproof should be kept in pools to minimize cage-related injuries, whereas those that are not waterproof should be kept inside in pens where it is warm. When assessing waterproofing using an IR photo, areas that were completely waterproof appeared cool (blues), because the feathers are preventing penetration of cold water, keeping the water on the surface of the feathers. Areas that appeared warmer (reds, yellows, oranges, greens) were not waterproof, because these areas are not insulated and are giving off heat. Identifying areas of heat loss/poor waterproofing is important, because those birds with insufficient waterproofing could become hypothermic if left in a cold water pool.

A) Thermograph of the ventrum of a Pacific Loon (P337), showing no areas of heat loss (completely waterproof ). B) Paired digital photo of P337 being held for an IR waterproofing check.

The results of this study indicate that thermography is effective for assessing surface body temperatures of seabirds and for assessing ventral waterproofing. This method proved less invasive and less time consuming than traditional methods. The potential benefits of using thermography to assess thermal stability of large numbers of oiled birds during an oil spill are great, and further research in this field is ongoing.