Spirinchus thaleichthys

Background

Figure 1: Longfin Smelt Adult Male. © Renée Reyes, all rights reserved.

Figure 1: Longfin Smelt Adult Male. © Renée Reyes, all rights reserved.

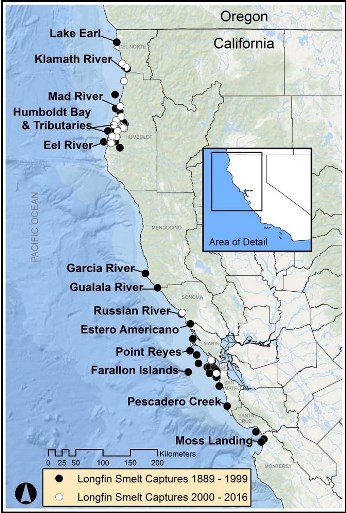

Figure 2: Historic (1999 or earlier) and current observations of Longfin Smelt north of the Bay-Delta. Garwood 2017.

Figure 2: Historic (1999 or earlier) and current observations of Longfin Smelt north of the Bay-Delta. Garwood 2017.

Longfin Smelt Spirinchus thaleichthys is a small fish in the family Osmeridae found along the Pacific coast of the United States from Alaska to California. In California, Longfin Smelt is historically found in the San Francisco Estuary and the Sacramento/San Joaquin Delta (Bay-Delta), Humboldt Bay, and the estuaries of the Eel River and Klamath River— and uses a variety of habitats from nearshore waters, to estuaries and lower portions of freshwater streams (Garwood 2017). The species is distinguished from other California smelt by the long pectoral fins that nearly reach the bases of the pelvic fins (Figure 1). Longfin Smelt are euryhaline, meaning they can tolerate a wide range of salinity from completely fresh to marine. Longfin Smelt is also anadromous, depending on fresh and marine waters for spawning and rearing.

Longfin Smelt typically live for two years, reaching lengths of about 90-124 mm fork length (FL) but can live a third year reaching maximum length of about 150 mm FL (Baxter 1999, Moyle 2002). Larvae move up and down in the water column to maintain position within the mixing zone of the Estuary where foraging on small shrimp-like crustaceans occurs.

Larval survey data from the Bay-Delta indicate spawning occurs from November through May, with a peak from February through April. Spawning in California is inferred from the presence of newly-hatched larvae. Eggs are thought to be released in freshwater over sandy, or gravel substrates, rocks and aquatic plants (Moyle 2002). Each female can lay between 5,000 and 24,000 adhesive eggs. Longfin Smelt is known to be a semelparous species, meaning they die after spawning.

Species Status

Longfin Smelt was listed as threatened under the California Endangered Species Act in 2009 (CDFG 2009). The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has found the San Francisco Bay-Delta Distinct Population Segment of Longfin Smelt warrants protection under the federal Endangered Species Act, but the listing was precluded.

Like Delta Smelt, scientists are seriously concerned about the decline of Longfin Smelt. It is part of the collective decline of pelagic fishes known as the Pelagic Organism Decline (POD) that also includes native Delta Smelt Hypomesus transpacificus, introduced Striped Bass Morone saxatillis, and introduced Threadfin Shad Dorosoma pentenense. The Pelagic Organism Decline Management Team (POD-MT) was formed by the Interagency Ecological Program (IEP) in 2005 to evaluate potential causes of the decline. The team developed several conceptual models to guide work plan development and integrate results. Work plans are updated as new information is learned (Baxter et al 2010 (PDF), IEP 2016 (PDF)).

Threats

Longfin Smelt was observed dating back to 1889, in diverse habitats north of the Bay-Delta such as coastal lagoons, bays, estuaries, sloughs, tidal freshwater streams and offshore (Garwood 2017). The causes of decline from northern estuaries are not clearly known, but they are probably similar to those of the Bay-Delta, which are multiple and synergistic. Some single causes outlined in Moyle (2002) include:

- Reduction in freshwater outflows

- Entrainment losses to water diversion

- Changes in food organisms

- Toxic substances

- Disease, competition, introduced species, and predation

- Loss of genetic integrity

In the Bay-Delta, the abundance of young-of-the-year Longfin Smelt increases with the amount of freshwater outflow. The fish seems to have a low tolerance to warm waters, with adults rarely found in water warmer than 64º F and young-of-the-year rarely found in water above 73º F (Hobbs and Moyle 2015). Warm water and decrease in flows are associated with drought conditions. Even though it appears the drought has ended, Longfin Smelt numbers may be so low that recovery could be difficult and slow. Hobbs (2017) warns these fish are so sensitive to temperature; any more warming is going to "be the end of them".

Loss of estuarine wetland and slough habitat may be an ongoing issue for the species. Longfin Smelt use these highly productive areas as adults before migrating up rivers to spawn, and as juveniles to rear and feed prior to entering the ocean (Garwood 2017). In addition, in the Bay-Delta, the reduction in Delta outflow due to water exports threatens survival and recovery. Delta outlflow refers to all of the water that is coming from the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers minus the water that is exported. Increased outflow increases the rate of fish transport into suitable rearing habitat in Suisun and San Pablo bays and reduces the probability of larvae spending too much time in the Delta where they are exposed to entrainment, pesticides, and other hazards.

Research, Conservation, and Management

Within California, much of what we know currently about the species is within the Bay-Delta and its tributaries, although Longfin Smelt is still found in north of the Bay-Delta (Figure 2). To help recover populations of this threatened species in the northern regions, restoration of former wetlands is needed in areas such as Humboldt Bay and the estuary of the Eel River, as these areas include both available habitat and existing populations (Garwood 2017). Garwood also recommends a systematic effort (that includes new methods such as environmental DNA) designed specifically for detecting Longfin Smelt to determine the current presence of the species in watersheds along the coast.

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife monitors the distribution and abundance of Longfin Smelt in the Bay-Delta using long-term monitoring surveys (see Related Information). This work is conducted as part of the IEP, the group of state and federal agency scientists dedicated to the collaborative monitoring, researching, modeling, and synthesizing of critical information for planning and regulatory purposes relative to endangered fishes and the aquatic ecosystem of the Bay-Delta.

References

- Baxter, R. D. 1999. Osmeridae. Pages 179-216 in J. Orsi, editor. Report on the 1980-1995 fish, shrimp and crab sampling in the San Francisco estuary. Interagency Ecological Program for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Estuary Technical Report 63.

- Baxter, R., R. Breuer, L. Brown, L. Conrad, F. Feyrer, S. Fong, K. Gehrts, L. Grimaldo, B. Herbold, P. Hrodey, A. Mueller-Solger, T. Sommer, and K. Souza. 2010. Interagency Ecological Program 2010 Pelagic organism decline work plan and synthesis of results through August 2010. Interagency Ecological Program for the San Francisco Estuary.

- CDFG. 2009. California Department of Fish and Game report to the Fish and Game Commission: A Status Review of the Longfin Smelt Spirinchus thaleichthys in California, January 23, 2009.

- CDWR. 2017. California Department of Water Resources IEP web page.

- Garwood, R. S. 2017. Historic and contemporary distribution of Longfin Smelt (Spirinchus thaleichthys) along the California coast. California Fish and Game Journal, Vol 103, Num 3.

- Hobbs, J. A. 2017. Little Fish in Big Trouble: The Bay Delta’s Longfin Smelt, an article as part of KCET and Link TV’s “Summer of the Environment” by Alastair Bland, May 17, 2017.

- Hobbs, J. A. and P. B. Moyle. 2015. Last Days of the Longfin? News Deeply-Water Deeply, September 8. 2015.

- Interagency Ecological Program (IEP). 2016. Annual Work Plan, April 4, 2016.

- Moyle, P. B. 2002. Inland Fishes of California. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

CDFW

USFWS

IEP

Delta Stewardship Council

Prepared by: Mary Olswang

Last updated: January 3, 2018