Ian holds a wild hen pheasant trapped at night at the Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area as part of his extensive research into California’s wild pheasant populations.

Ian with his wife and son.

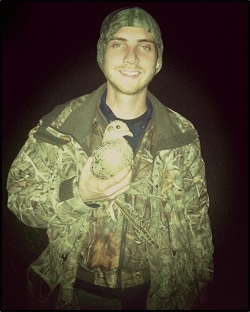

Ian holds a wild duck trapped at the Grizzly Island Wildlife Area so the bird can be outfitted with a radio transmitter to better understand migration patterns and habitat usage.

A greater sage grouse captured in Nevada in 2017 carries a radio collar as part of a research project looking at how certain landscape uses such as grazing and energy development impact sage grouse populations.

California’s wild pheasant season opens the second Saturday in November every year. For many hunters, however, pheasant season is something of a phantom opportunity on the hunting calendar as wild ring-necked pheasants (Phasianus colchicus), a farmland species once omnipresent throughout the Central Valley’s agricultural regions and rural backroads, have largely disappeared from the California landscape. Remnant, huntable populations of wild birds remain on some state wildlife areas, federal wildlife refuges and on pockets of private property but many pheasant hunters in California today pursue pen-raised birds released on licensed game bird clubs and other private ground or travel out-of-state to destinations in the Midwest where wild pheasants are still abundant.

Ian Dwight, an environmental scientist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (CDFW) Upland Game Unit, has spent the bulk of his professional career researching California’s wild pheasants, beginning with his graduate studies at UC Davis, from which he earned a bachelor’s degree in wildlife, fisheries and conservation biology and a master’s degree in avian sciences. Prior to joining CDFW in 2022, Ian spent nine years with the U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) Western Ecological Research Center in Dixon, where he collaborated with CDFW scientists and other researchers in studying the long-term decline in California’s pheasant populations (PDF) and explored greater sage-grouse population dynamics in Nevada.

A native of Elk Grove in Sacramento County, Ian grew up hunting wild pheasants, waterfowl and other game bird species in the Sacramento Valley. Today, he is responsible for supporting upland game bird management in California, including improving habitat for upland game birds and waterfowl, and pursuing efforts to reverse the state’s wild pheasant decline.

Ring-necked pheasants are a nonnative species. Should we really care that much about them?

Although pheasants are nonnative, they share a lot of the same life history needs as other native species. They’re fairly easy to monitor because they vocalize during the breeding season, so we can track their calls and gain information on relative abundance and how that changes year-to-year. So, pheasants really are good candidates in terms of being indicators or surrogates for other upland and grassland birds in California.

Beyond an indicator species, there is just a lot of care, love and passion surrounding the tradition of pheasant hunting. They’re charismatic – beautiful birds, especially in hand. We have small towns in California that sprouted up years ago along the I-5 corridor and elsewhere as a direct result of pheasant hunting. We don’t see that kind of thing happening anymore, but both in terms of their value as an indicator species and as a hunting resource, pheasants are important.

Every California hunter, it seems, has a different theory behind the decline of wild pheasants. Some blame an increase in predators, others mosquito abatement, some West Nile virus and still others say clean farming. As a scientist who has researched this topic perhaps more than anyone else in California, what’s really to blame?

I’d say they’re all right, in a way. It’s the cumulative, long-term effects of many different things that have impacted pheasants as time has gone on.

The main phenomenon I’d point to is the changes in farming practices that occurred in the 1980s and 1990s, namely clean farming practices, the elimination of hedgerows, the burning of canals and ditches, the use of herbicides to the point where the amount of cover and visual obstruction pheasants need to escape predation are no longer there. Not only that, but there have also been changes in the types of crops planted in California that are no longer advantageous to pheasants. The decrease in the planting of wheat, barley and cereal grains – sugar beets, too – has coincided with these clean farming practices. At the same time, you have increases in other crops that aren’t as advantageous such as rice and orchards across the Central Valley. As we decrease the amount of available cover and as we decrease the advantageous crops, you really decrease the carrying capacity for pheasants on the landscape.

Additionally, the fact that burning rice stubble is no longer allowed on the same scale it was in the 1990s is also a factor as is the increase in pesticides that eliminates potential food resources for chicks. The same argument has been made for mosquito abatement applications. So, there’s just a myriad of factors that have all culminated more or less at the same time over the last 30 years or more to impact populations.

How do you explain the pheasant decline on state wildlife areas and federal refuges that don’t see that same kind of intensive agriculture use? The Gray Lodge Wildlife Area today still provides more than 9,000 acres of wildlife habitat just as it did 20, 30, 40 and 50 years ago when wild pheasants there were super abundant. As recently as 1998, hunters harvested almost 2,000 pheasants at Gray Lodge (PDF).

Well, I think if you were to look at satellite imagery of Gray Lodge over time, even from 1998 to today, you’d notice a pretty big difference. And that’s primarily the loss of upland habitat, the division of upland units, and the increase in seasonal wetlands and tree canopy.

Pheasants at Gray Lodge have declined for several reasons: They are cut off from other self-sustaining populations and lack contiguous blocks of upland habitat. They are surrounded by orchards and rice on neighboring properties. They get pounded by mosquito abatement during the summer when chicks have hatched and the area floods up certain units for moist-soil management or for grazing during the breeding season, which knocks out active nests on the ground. Not to mention there has been an increase in avian predators such as ravens and raptor species that take advantage of that mature tree canopy Gray Lodge offers.

When I was at USGS, we made a considerable effort trying to trap and radio monitor pheasants at Gray Lodge to try to understand nest and brood survival. The bottom line is that we had so much trouble finding and catching female pheasants at Gray Lodge that it was really hard to get a lot of information from such low sample sizes.

Is there any hope for wild pheasants in California?

Absolutely. If we as an agency are willing to continue our work providing habitat incentives to private landowners that will help reverse the trend. I’m speaking specifically about our incentive programs like the California Waterfowl Habitat Program, also known as the Presley Program, the Nesting Bird Habitat Incentive Program, the Permanent Wetland Easement Program and the California Winter Rice Habitat Incentive Program. Working with private landowners surrounding our wildlife areas and refuges to increase the overall amount of habitat on the landscape is key. If we can get to the point where we are putting habitat on the ground, not only at our public hunting areas but also on private lands, then we can really increase the carrying capacity of the landscape. It’s a matter of providing what pheasants need to carry out their life history.

What about all the recent interest in pollinators and pollinator habitat? Isn’t that another encouraging development for upland game birds? Don’t bees and butterflies share some of the same habitat needs as quail and pheasants?

Great question. One of the important components of pollinator habitat is flowering forbs and the diversity of flowering forbs you have in a given field. Well, that benefits pheasants in two ways. First, there are bugs of all kinds for pheasant chicks, which depend on insects for the first few weeks of their lives. That pollinator habitat also provides cover -- and escape cover from predators as well. When you have a mosaic of grassland habitat for nesting and forbs and pollinator habitat for brood-rearing, I think you have a really good mix. It’s an important composition to have for breeding ducks as well as pheasants.

A great example of this is at the Grizzly Island Wildlife Area. There’s a pretty big restoration effort happening in the northwest corner of the wildlife area. More than 1,000 acres of upland habitat is being restored or enhanced that at one time was chopped up into little fields. We are in the process of removing levees and irrigation ditches to create contiguous blocks of pollinator habitat and upland habitat for nesting ducks and pheasants. The project will be completed over the next several years.

Is CDFW conducting any current research on pheasants?

We piloted a study this year in which we deployed a number of autonomous recording units – what we call ARUs – at several different state wildlife areas and federal refuges to detect pheasant abundance. We had these ARUs listening for upland birds vocalizing during the breeding season before and after sunrise. What we do is take these recordings and upload them to a detector for bird sounds called BirdNET. It works similar to the Merlin Bird ID app you can download to your phone. Ours was developed by Cornell University, and we can very quickly feed hours and hours of sound files into this detector and it can tell us the species of bird being detected, the time of detection and the confidence that the detection is true. I deployed eight units in total at the Upper Butte Basin Wildlife Area at both Little Dry Creek and at Howard Slough and I’d like to double that number next year. We had four recording units at Gray Lodge, 10 at Lower Klamath and another 10 at the Honey Lake Wildlife Area.

The detectors worked pretty well in terms of correctly identifying pheasants, turkeys, quail and dove. I think ARUs can be a cost-effective tool for monitoring bird populations without physically having to be present to detect these animals. We can bring that data into a monitoring framework and learn something about relative abundance by looking at the number of individuals vocalizing during a given time interval. It could at some point be a complement or perhaps an alternative to traditional surveys driving around and counting birds or listening for calls. It’s not just valuable for pheasants and game birds but other species as well. The Upper Butte Basin Wildlife Area is particularly interested in detecting the occupancy of western yellow-billed cuckoo, which is a state- and federally listed species. So, I think there is a lot of potential for these autonomous recording units and leveraging technology so we can be in more places at the same time.

Would CDFW ever consider reaching out to states such as South Dakota or North Dakota to acquire some of their wild pheasants to bolster California’s populations or improve the genetic diversity of the populations we have here?

I’d like to see a lot more habitat creation and improvement before we take birds from somewhere else and put them on the landscape. I think some of our wildlife areas have a better chance at creating and maintaining healthy pheasant populations than others. The Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area is a great example because of the size of the area and their uplands. Currently, hunters at the Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area harvest 50 percent of all the publicly taken wild pheasants in California. I think Grizzly Island, potentially, will be another great pheasant area with all the restoration efforts and infrastructure improvements under way.

One of the places that we’re eyeing as a source for translocations is the Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex. It’s probably one of the few places in the state that still have wild pheasants consistently every year. But the habitat up there has suffered greatly because of the lack of water, so now there is a really big concern that those pheasants will begin to decline if the complex doesn’t get more water. I’m hopeful that the situation will change for the better. If the Klamath complex can get water again, we potentially could have a great source population of wild pheasants in northeastern California to translocate to public wildlife areas in the Central Valley. Right now, however, we are monitoring those populations and evaluating our next move.

Photos courtesy of Ian Dwight