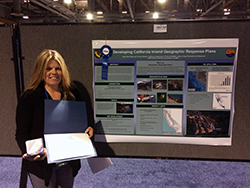

Anna Burkholder is a senior environmental scientist with the Preparedness Branch of CDFW’s Office of Spill Prevention and Response (OSPR) in Sacramento. She is the statewide Inland Geographic Response Plan Coordinator, working with fellow OSPR staff throughout the state to develop inland response plans for waterways at high risk for an oil spill. She has worked for CDFW for 20 years, most recently joining OSPR in 2016. In addition to her role as response plan coordinator, she is training for two oil spill emergency response positions: wildlife branch director (the position that oversees wildlife response efforts during a spill) and liaison officer (which works to address stakeholders’ concerns during a spill).

Anna earned her Bachelor of Science degree in biology, with an emphasis in zoology, from San Francisco State University. She prefers being outdoors, hiking with her dogs, snowshoeing, paddle boarding and horseback riding. She volunteers with the DOVES Guidance Program, a therapeutic horseback riding program for at-risk kids, as well as for NorCal German Shorthaired Pointer Rescue. She is improving her skills at upland bird hunting, including pheasant and turkey, and is still waiting to take a shot at her first tom.

Who or what inspired you to become a scientist?

When the movie Jaws came out, I was both terrified and fascinated. To this day, it is my favorite movie and I am more thrilled than ever with sharks. I briefly met Peter Benchley, the author of Jaws, several years back at the Monterey Bay Aquarium and that was exciting. He was promoting a new book trying to dispel the terrifying image of Great Whites, which he felt partially responsible for creating. I was also inspired by Dr. John McCosker, a Great White Shark expert that works for the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. McCosker had begun investigating why shark attacks occur, assessing their danger to humans in the grand scheme of things. He has worked to help understand the importance of sharks in the ecosystem and how they relate to the health of our oceans.

What got you interested in working with wildlife?

Clearly I would have loved to study sharks but didn’t follow that path. Along the way though, some of my classes at San Francisco State got me interested in some aspects of wildlife. Studying the behavior of snow leopards at the San Francisco Zoo (they sleep a lot!) for my Animal Behavior class, and doing some mark and recapture studies of mice and voles in Pacifica for an Ecology class, were fun experiences.

Who or what brought you to CDFW? What inspires you to stay?

Pure luck brought me to CDFW. After I graduated from college, I was working for a biotech company in Hercules and wasn’t terribly happy with the work. I used to go for walks during my break time and look out over San Pablo Bay and think to myself, “I need a job out there.” While taking an oceanography class at night at a junior college, I was looking at the job board one evening and saw a posting for a temporary scientific aid position with CDFW, working on the Bay Study Project. I got the job and lo and behold, there I was out on a boat every month, sampling fish throughout the Delta and San Francisco Bay (including San Pablo Bay!). I have never looked back.

Twenty years later, I guess it was a good move for me. I stay because I love this department, mostly the people I work with, and the dedication and passion we all have for the environment and the strong desire to protect the species and habitats in the state.

What is a typical day like for you at work?

When I am not traveling to participate in oil spill drills, oil spill workshops or Incident Command System training, I spend time working on the Geographic Response Plan template document that will be used to produce regional plans throughout the state for oil spill response. I coordinate with my OSPR colleagues, as well as other state and federal agencies, oil spill response organizations and industry folks on the development of these documents so they can provide a useful tool in responding to an incident. It’s been great to meet and work with an entirely new set of folks that I haven’t come across in my career until now, and to have a common goal of preparing for oil spills and working to protect the public, the environment and economic resources in our state.

What is the most memorable or rewarding project that you’ve worked on for CDFW?

I’ve spent a lot of time in the field working on boats. I worked on the 2007 Pike Eradication project at Lake Davis, and even got to spend a day escorting Delta and Dawn, the wayward humpback whale cow and calf that swam up the deep water channel to the Port of Sacramento in 2007. We escorted them on the last day they were observed inside the Golden Gate as they made their way through San Pablo Bay and finally back out to the Pacific Ocean.

I would have to say the most rewarding project is shaping up to be my new job with OSPR. The office was established 25 years ago and has a very comprehensive marine program in terms of preparedness and response to oil spills, but since OSPR’s jurisdiction expanded to include inland in 2015, I get to be on the forefront of establishing preparedness plans to protect all waters of the state.

What do you enjoy most about your job?

I work with an amazing group of folks in every part of our department, and we have a common goal of preserving and enhancing the natural environment. Being able to feel proud of the department you work for and cheering on the achievements of others in your field is a great feeling. Not to mention some of the great days in the field, which include flying along the California coast to record data on nesting seabirds, looking for nesting grebes in high mountain lakes and touring the state’s bird and marine mammal rescue and rehabilitation facilities.

Is there a preconception about scientists you would like to dispel?

The term “environmental scientist” encompasses a wide range of job duties within the State of California, including field biologists and environmental planning and permitting staff. We certainly have state scientists who conduct important laboratory research, including folks who work for OSPR and conduct water analysis and DNA fingerprinting on oil products. And what’s wrong with a periodic table? I loved general chemistry class!

Do you have advice for people considering careers in science or natural resources?

If it is what you love to do, then don’t shy away from following that path. You can try different aspects of working in the natural resources field and then focus on what you enjoy the most. I would volunteer or take shorter-term assignments to work with multiple organizations and get experience in different areas. Meet experts in their field and get a foot in the door through internships or part-time jobs. There are so many exciting directions you can go in this field.