Kelly McCulloh loads evidence samples onto a DNA extraction robot.

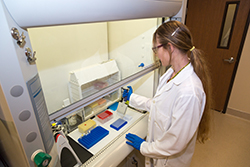

Jillian Adkins prepares samples for DNA extraction.

Erin Meredith uses a dissecting microscope to isolate hair roots for nuclear DNA extraction.

Ashley Spicer prepares a Polymerase chain reaction used in DNA sequencing.

If they weren’t so busy or their work wasn’t so mission-critical, you might find CDFW’s Wildlife Forensics Laboratory team on loan to the California Department of Education.

The four-person scientific team is all women with undergraduate and advanced degrees in biochemistry, genetics, molecular biology and forensic science.

Jillian Adkins, Kelly McCulloh, Erin Meredith and Ashley Spicer would be stars of state education initiatives to attract more girls to STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) fields. They would be celebrated at school tours, asked to provide their personal stories at education conferences and inspirational messages in science classrooms across the state.

Instead, this team works mostly out of the spotlight, their scientific analysis critical to CDFW’s law enforcement mission to protect California’s natural resources and provide public safety. Increasingly, CDFW’s Wildlife Forensics Laboratory is being counted on to protect some of the most sensitive animal species on the planet.

“We just don’t lose these cases supported by forensic evidence. It’s amazing,” said Tony Warrington, a recently retired assistant chief who has managed CDFW’s crime lab for more than a decade. “Our forensic specialists do a fantastic job utilizing advanced scientific methods to support wildlife officers with poaching investigations and public safety wildlife incidents.”

Meredith, a senior wildlife forensic specialist with nearly 20 years at the lab, said the mere suggestion by a wildlife officer of sending evidence in for DNA analysis will sometimes prompt poachers to confess to their crimes. The lab is one of only about 10 wildlife forensic labs in the nation, giving CDFW wildlife officers a major crime-fighting assist. Every CDFW wildlife officer can access the lab, which processes evidence in about 100 criminal cases every year.

The white lab coats, antiseptic setting, high-tech equipment and talk of DNA sequencing invite comparisons to “CSI” – Crime Scene Investigations – the long-running night-time television drama that firmly implanted forensics in the public consciousness.

“My joke is always that human forensics is boring – you only work on one species,” Meredith said. “With wildlife, the possibilities are essentially endless.”

First established in the 1970s, CDFW’s Wildlife Forensics Laboratory has taken on a more prominent role with advances in genetic research and technology and the widespread acceptance of forensic evidence in the court system.

“If there’s blood on a knife, not only can we tell whether it’s from a deer, we can also tell whether it’s from a doe or a buck,” Meredith said. “We can tell if the blood on the knife originated from the same deer or evidence taken from a kill site or meat in a suspect’s freezer.”

Said Adkins, “DNA evidence has been a game-changer in determining guilt or innocence – in both people and wildlife.” Adkins’ work in providing quick turnaround of DNA samples allows wildlife officers to use the results to make critical enforcement decisions.

CDFW’s Wildlife Forensics Lab plays a key role in public safety and animal attacks that may involve great white sharks, coyotes, bears or mountain lions. With even minimal DNA evidence, offending species and animals can be identified with certainty in most instances.

“We literally free the innocent – and it’s happened a number of times,” Meredith said. “Our wildlife officers may trap what they think is the guilty bear, draw its blood and bring it to the lab for comparison with saliva from a bite wound or even a scratch mark on the victim. And if that DNA is not a match, that bear gets released.”

Retired assistant chief Warrington said, “This lab completely changed the way we deal with public safety wildlife. DNA matching has allowed CDFW to protect the innocent and positively identify the offending animal in these cases – a big step forward in protecting California’s wildlife.”

The lab marked another milestone in 2015 with the adoption of Assembly Bill 96, which closed a loophole in the state’s ban on ivory and made it illegal to purchase, sell, possess with intent to sell or import with intent to sell ivory or rhinoceros horn – with limited exceptions.

The legislation tasked a state wildlife agency with helping to combat the global ivory trade in order to protect ivory bearing species from poaching, exploitation and extinction worldwide. AB 96 provided funding for CDFW’s Wildlife Forensics Lab to add a fourth scientist in McCulloh.

McCulloh arrived with a master’s degree in forensic science from UC Davis. She has pioneered California’s genetics test for ivory products. It’s so accurate, it can distinguish African elephant ivory from Asian elephant ivory and even ivory from a long-extinct woolly mammoth.

Spicer, a native of British Columbia with degrees in biochemistry and forensic science, specializes in the physical characteristics of ivory that distinguish it among the many different ivory-bearing species – from elephant and hippopotamus to sperm whale and warthog – and also from non-ivory products such as synthetic ivory or plastics made to look like ivory.

Spicer personally has worked on 17 of the 18 criminal ivory cases that have come through the lab since AB 96 was enacted. Her work has included serving as an expert witness and testifying at trial.

The lab’s contributions were  heralded recently in the conviction of a Los Angeles County business owner on charges of selling two ivory tusks from Arctic narwhal whales. The tusks measured 79 and 89 inches long.

heralded recently in the conviction of a Los Angeles County business owner on charges of selling two ivory tusks from Arctic narwhal whales. The tusks measured 79 and 89 inches long.

CDFW’s forensic scientists don’t necessarily mind all the newfound recognition – as long as the focus remains on their work.

Said Spicer, “We are really committed to the highest standards and ideals of science.”

YouTube Video Link:  https://youtu.be/4KS4e3ILKOw

https://youtu.be/4KS4e3ILKOw

CDFW Photos. Top Photo: The four-woman forensics team.