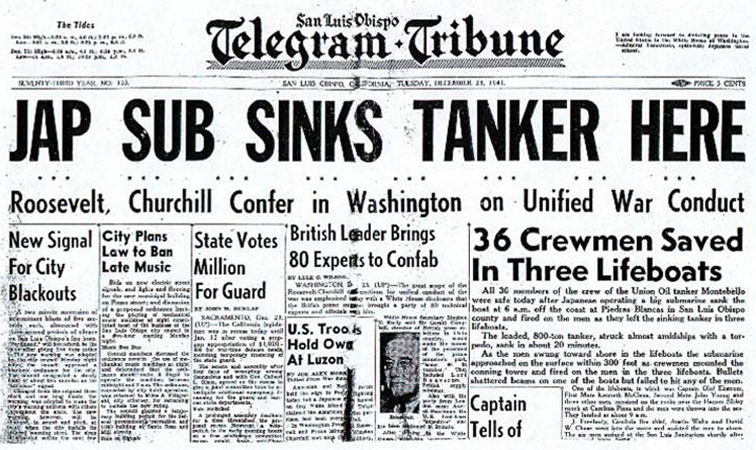

San Luis Obispo Telegram Tribune from December 24, 1941

San Luis Obispo Telegram Tribune from December 24, 1941

The San Luis Obispo Tribune, September 30, 2007

By Dan Krieger

The Untied Press teletype read: “The S.S. Story outran a torpedo attack off Point Arguello. The S.S. Larry Doheny was shelled by an enemy submarine but reached port safely. Press reports of the sinking of the S.S. Montebello are confirmed.”

Wartime reports for Dec. 24, 1941 appeared in the Port Arthur (Texas) News, the Sheboygan (Michigan) Press, and the San Francisco Call. Copies of the Call were quickly rounded up by federal agents.

A full report of the early morning sinking of the Union Oil tanker S.S. Montebello appeared in a special edition of this newspaper, then called the Telegram-Tribune, on Dec. 23, 1941, the afternoon the Montebello sank.

San Luis Obispo was sufficiently isolated, so no effort was made to confiscate the papers.

Union Oil Co. eventually sued the federal government for failing to protect maritime shipping in U.S. coastal waters.

Unocal lost the case before the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals when the government proved that the Montebello actually had hit the ocean bottom lightly more than three miles off the Cambria coast in international waters.

The reports of these attacks and more than a dozen others were denied by federal authorities. No mention of the attacks will be found in the Navy Department’s 15-volumne “History of the United States Naval Operations in World War II,” edited by Samuel Eliot Morison.

Morison was a Harvard history professor who won two Pulitzer Prizes, on for a two-volume history of the voyages of Christopher Columbus entitled “Admiral of the Ocean Sea,” and the other for a definitive biography of John Paul Jones. His students included members of the Roosevelt family and future President John F. Kennedy.

His naval histories have been praised by British historian Sir John Keegan as “the best history to come out of the Second World War.” Keegan is considered one of the greatest living military historians.

Morison was commissioned as a lieutenant commander in the Navy when he began the history project. He was promoted to the rank of rear admiral (reserve). The frigate USS Samuel Eliot Morison was named in his honor, and a bronze statue of Morison stands near commonwealth Avenue in Boston.

Morison was criticized for his insensitivity to the indigenous people of the Americas and to the incredible cruelty of slavery in his two-volume “Growth of the American Republic,” written with Henry Steele Commager.

This was the standard history textbook used during the 1950s and early ’60s at colleges throughout America.

Most historians would agree that Morison’s errors were products of his time and social status as a member of Boston’s elite. But they also would argue that Morison tried to present facts as honestly as he saw them.

Why, then, does he not mention the submarine attacks along the Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo county coast in the official naval history?

I asked this question to Arthur J. Marder, one of Morison’s students who himself became a famous naval historian of the British and Japanese navies during the early 20th century.

Marder, then retired from UC Irvine, was not my teacher but had become my mentor through associations in the Conference of British Studies and the American Historical Association.

Marder respected me but thought this then-brash associate professor could learn a thing or two. He replied, “My goodness, haven’t you hear of the ‘clear and present danger test’?” He meant that you do not shout, “Fire!” in a crowded theater.

He claimed that disclosing the information would have been similar even after Japan’s surrender, as America entered the Cold War, revealing American’s total vulnerability in 1941.

The unsuccessful torpedoing of the Standard Oil Co. tanker H.M. Story off Point Arguello on Dec. 22, 1941, the attempted torpedoing and shelling of the Atlantic-Richfield tanker Larry Doheny on the evening of Dec. 22, and the sinking of the Montebello the next morning were all the work of the Japanese Navy’s Submarine I-21, under the command of Captain Kanji Matsumura.

That sub and the I-17 that shelled a refinery, oil station and restaurant at Ellwood, 12 miles north of Santa Barbara, was part of the Japanese Navy’s 1st Submarine Squadron that waited off the entrance to Pearl Harbor the evening of Dec. 6, 1941. Its mission was to destroy any American ships that tried to escape the aerial attack.

After the attack, the squadron was dispatched to our mainland shores. Here it sank several vessels, including the Montebello, and inflicted psychological damage.

Marder felt this information was too inflammatory for the American public to know until the 1960s.