Uvas Creek watershed, southern Santa Clara County

Species / Location

Figure 1. Adult steelhead previously documented in Uvas Creek on March 15, 2012. (Photo: NOAA Fisheries)

Figure 1. Adult steelhead previously documented in Uvas Creek on March 15, 2012. (Photo: NOAA Fisheries)

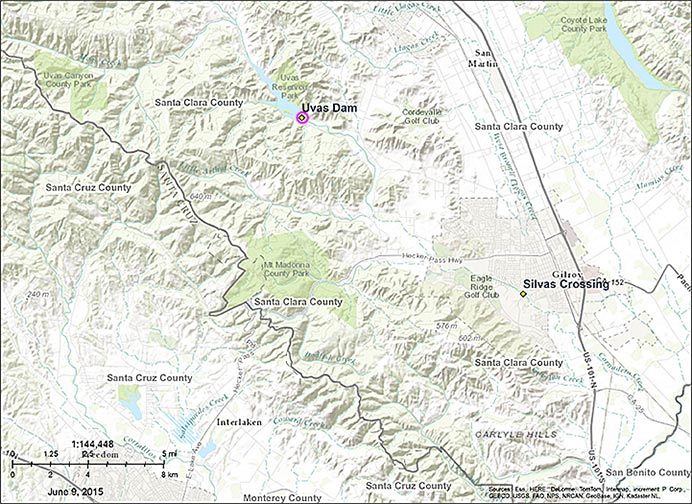

Figure 2. Map of Uvas Creek in Gilroy where monitoring occurred.(click/tap to enlarge)

Figure 2. Map of Uvas Creek in Gilroy where monitoring occurred.(click/tap to enlarge)

Uvas Creek, tributary to the Pajaro River in southern Santa Clara County, has supported a run of South Central California Coast steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss), a federally threatened species and state Species of Special Concern. Steelhead are “anadromous,” meaning they spawn and rear in fresh water for 1-2 years, then the young fish migrate to the ocean where they reach adulthood before returning to their natal streams to spawn (Figure 1).

Need for Drought Stressor Monitoring

Monitoring of juvenile steelhead has been conducted in Uvas Creek by U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries and San Jose State University biologists since 2005 (Figure 2). Results from past surveys indicated overall juvenile numbers had decreased considerably since the early 1970s. Since the start of the current drought in 2012, steelhead numbers have dropped sharply, and this year have all but disappeared. Once funded, implementation of the California Coastal Monitoring Plan would add to localized monitoring efforts to provide more resolution to population status and trend statewide and in Santa Clara County streams.

Stressor Monitoring Efforts and Findings

The season began on a hopeful note at the end of this last year (2014). Between October 1 (the official start of the water year) and December 31, over 10 inches of rain was recorded in the Santa Clara Valley. The “pineapple express” storm of December 11, alone, brought nearly four inches of much-needed rain. Steelhead typically enter streams to spawn between December and March, so everyone geared up for the return of spawning adult fish to the Uvas Creek watershed. But despite the rainfall, Uvas Creek remained mostly dry, or flowed only briefly. The water table and surrounding landscape were so parched from the long, hot summer and the previous years of drought that the rain that fell soaked quickly into the ground and did not generate enough runoff to provide the sustained flows needed by migrating fish. Only one other substantial storm (on February 5) occurred this past winter. The two storms were enough to fill Uvas Reservoir to 75% capacity by February 10 (Figure 3). By contrast, the reservoir was only at 3% capacity on February 4, 2014 (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Uvas Reservoir on February 10, 2015.

Figure 3. Uvas Reservoir on February 10, 2015.

Figure 4. Uvas Reservoir on February 06, 2014.

Figure 4. Uvas Reservoir on February 06, 2014.

Silvas’ Crossing, a low water ford on Miller Avenue near Christmas Hill Park in Gilroy, is an easy spot to check stream flow and, typically, to see migrating steelhead in Uvas Creek. Within ten days of the December 11 storm, conditions appeared to be similar (dry) to what they had been for the previous ten months (Figure 5A and 5B).

Figure 5A. Silvas’ Crossing, Uvas Creek on December 16, 2014

Figure 5A. Silvas’ Crossing, Uvas Creek on December 16, 2014

Figure 5B. Silvas’ Crossing, Uvas Creek on January 12, 2015

Figure 5B. Silvas’ Crossing, Uvas Creek on January 12, 2015

CDFW and its local partners looked hard for any sign of fish that might have been able to make it upstream from the ocean through the Pajaro River and into Uvas Creek. Despite many long hours of searching, walking the creeks, and knocking on doors asking property owners along the stream for information, no steelhead were observed in 2014/2015 spawning season. For the third year in a row, minimal (if any) spawning occurred in Uvas Creek. Most yearling steelhead from the 2013 year class likely had been wiped out when Uvas Creek dried back in 2014. This year, we expect there to be very few juvenile steelhead produced in Uvas Creek because of the ongoing drought.

Rainfall Totals Only Slightly Below Average, So Why is The Stream Still Dry? According to the National Weather Service’s website, rainfall totals as of May 7, 2015 for the Santa Clara Valley were 90% of average. That sounds good, but the majority of the rain fell in only two big storms, without a series of smaller storms in between. This means the reservoirs could fill, capturing and storing potential flow in the upper watershed to later be used for water supply (ground water recharge) and the benefit of aquatic resources. The degree to which this has affected downstream groundwater recharge and flows has not been quantified. What is known is that after consecutive years of drought, badly needed soil saturation and groundwater recharge, which allows streams to flow through the dry season, did not occur. As a result, Uvas Creek very quickly went dry once skies cleared after each storm. This also means that it does not appear that there was sufficient flow in the creek to enable adult steelhead to migrate in from the ocean and spawn. After the December storms, no rain fell in January 2015; it was the warmest and driest January on record. Uvas Creek once again exhibited dryback patterns during the winter which are normally not seen until the summer months.

Future Efforts

Outlook for Uvas Creek Steelhead is Uncertain. The run of steelhead in Uvas Creek has been hit hard by this sequence of three years of drought. Even though precipitation as of March in water year 2015 stands at 90% of normal, pre-existing drought conditions resulted in rapid and severe dryback in Uvas Creek after each storm had passed. Long stretches of very thirsty, dry stream bed between the ocean and spawning grounds in Uvas Creek soaked up any rain that fell. This, coupled with very brief periods of time when flows were sufficient for fish to swim upstream, prevented adult steelhead from migrating upstream to spawn.

Droughts are not unheard of in California, although some researchers have stated that the length and severity of the current drought has not been seen in 1,200 years (Griffin and Anchukaitis 2014). Nevertheless, steelhead, compared to other species in the salmon family, have very flexible life history strategies. CDFW biologists are hopeful that once sufficient rainfall has returned to the watershed, groundwater tables will be replenished, and the stream will have sufficient flow once again to re-establish the steelhead population in Uvas Creek to healthy levels.

References

- Griffin, D., and K. J. Anchukaitis. (2014), How unusual is the 2012–2014 California drought?, Geophys. Res. Lett., 41, 9017–9023, doi:10.1002/2014GL062433

CDFW

NOAA Fisheries

Coastal Habitat Education and Environmental Restoration