(Tributary to San Joaquin River, Stanislaus County)

Species Status

(click/tap to enlarge)

(click/tap to enlarge)

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) recognizes five Evolutionary Significant Units of Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) in California based on life history and genetic similarities among nearby populations (Moyle 2002). The Central Valley Chinook salmon ESU covers fall-run and late fall-run salmon in the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers and tributaries. This ESU is considered a species of concern and a candidate for Threatened status by NMFS. Central Valley rivers and streams are also home to Central Valley Steelhead Trout (O. mykiss), listed as Threatened under the Federal ESA and non-anadromous rainbow trout (O.mykiss). In the Stanislaus River, spawning habitat for both species ranges from below Goodwin Dam to roughly 13 miles downstream (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Salmon carcasses, Stanislaus River

Figure 1. Salmon carcasses, Stanislaus River

Figure 2. O.mykiss spawning redd, Stanislaus River

Figure 2. O.mykiss spawning redd, Stanislaus River

Necessity of Rescue

Figure 3. Goodwin Dam, Stanislaus River, CA

Figure 3. Goodwin Dam, Stanislaus River, CA

The Stanislaus Operations Group (SOG) is composed of staff from the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), US Bureau of Reclamation (USBR), US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), California Department of Water Resources (DWR) and California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW). This group is tasked with managing flows via Goodwin Dam (Figure 3) on the Stanislaus River to protect native fish stocks. In March 2016, SOG agreed on a pulse flow schedule that included several high flow peaks to encourage juvenile salmon out-migration before river water temperatures would increase during the summer months. The first peak was scheduled to occur on April 3, 2016 and reach 800 cubic feet per second (cfs) and recede to 200 cfs on April 5, 2016. This abrupt decline in flow caused concern, because 800 cfs would activate flow through some otherwise dry side-channels, causing juvenile salmonids to become trapped when flows abruptly receded. Fish trapped in diminishing pools would be subject to low dissolved oxygen, high temperatures and predation. The CDFW chose to monitor known sites with stranding potential post- drop in flow.

Locations

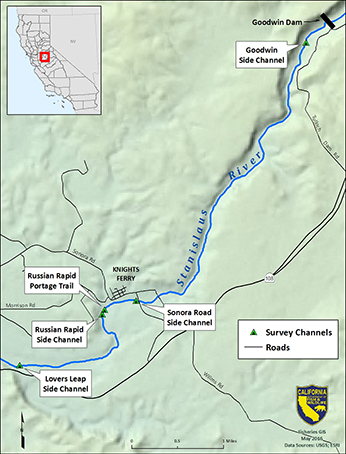

CDFW selected five survey sites in a 6 mile stretch downstream of Goodwin Dam. Goodwin Dam is located at river mile (RM) 58.4 (meaning this location is 58.4 miles upstream of the Stanislaus River confluence with the San Joaquin River). Site-1, known at the Goodwin Side Channel (GSC) is located at RM 58.1. GSC runs through a small riparian area into an exposed gravel pool before flowing back into the main channel. Site-2 is the Sonora Road Side Channel (SRSC) and is a heavily vegetated side channel that begins just downstream of the Sonora Road Bridge in Knights Ferry at RM 54.5. Site-3 and site-4 are both near Russian Rapids at RM 53.9. Site-3 is a portage trail (RRPT) that inundates and flows like a side channel. Site-4 is a natural side channel near Russian Rapids (RRSC) that flows through a heavily wooded area. Site-5 is the Lovers Leap Side Channel (LLSC) which is an engineered floodplain and side channel at RM 52.4 (see map).

Methods

Peak flows occurred as scheduled and CDFW conducted surveys at all five sites on April 6, 2016. The first step was to ascertain if channels were activated during the 800 cfs peak flow by visually inspecting each site for water lines, standing water and clues left by flowing water through the area. If it appeared that inundation occurred, the crew searched for areas of standing water and fish mortalities. When areas of standing water or isolated pools were found, crews probed the water with dip nets looking for live fish, and water quality (temperature and dissolved oxygen) was measured. When fish were found in a pool, the crew searched to see if the pool was connected to the main channel in any way. If there was no connectivity to the main channel and a chance for fish to move on their own volition, several passes were made with dip nets and seine nets to capture trapped fish. Captured fish were measured, checked for any marks and released back into the river into the nearest suitable habitat.

Results

Two of the five sites (site-1 and site-4) were inundated during the peak flow, and 48 salmonids were identified from both sites during the April 6, 2016 surveys (Figure 4). Fish observed in the pools were very small. Average fork length for O. mykiss and Chinook salmon was 30.5 millimeters (mm) and 43.7 mm, respectively. All rescued salmonids were released back to the Stanislaus River. There were three Chinook salmon mortalities (Figure 5) in a site-4 pool, likely due to low dissolved oxygen (2.80 mg/L).

The number of trapped fish caused by the sudden drop in flow is likely a low estimate of the total impact for two reasons. Some pools were deep and rocky and surrounded by dense vegetation, which made it difficult for crews to access and easy for fish to hide. The second reason was lack of time and resources. Only five sites were identified and surveyed, leaving potentially undiscovered isolated pools with fish.

Figure 4. Drying pool at RRSC site-4, Stanislaus River, CA

Figure 4. Drying pool at RRSC site-4, Stanislaus River, CA

Figure 5. Site-4 Chinook salmon mortality, Stanislaus River, CA

Figure 5. Site-4 Chinook salmon mortality, Stanislaus River, CA

Monitoring

In the following weeks more surveys should be conducted to visually inspect inundation and connectivity of side channels at various flows. Safe base flows (in between the peak flows) should be determined and included in future pulse flow recommendations.

Recommendations

To avoid stranding in the future, CDFW recommends maintaining higher flows in between peaks during pulse flows. For example, the sites where fish were rescued should remain connected to the river above 400 cfs.

References

- Moyle, P.B. 2002. Inland Fishes of California, University of California Press.

CDFW Region 4