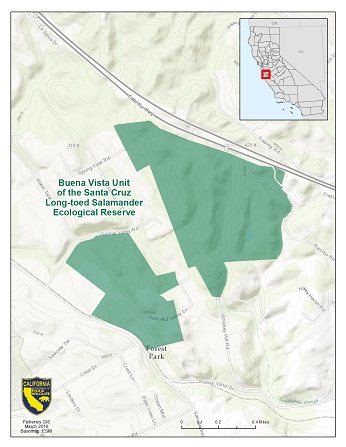

(Buena Vista Unit of the Santa Cruz Long-toed Salamander Ecological Reserve, Santa Cruz County)

Species / Location

(click/tap to enlarge)

(click/tap to enlarge)

The Santa Cruz Long-toed Salamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum croceum; SCLTS) is a federally and state-listed endangered species and a fully protected species. It has a very restricted range in southern Santa Cruz and northern Monterey counties and primarily occupies ephemeral wetlands and adjacent uplands. Most of their habitat has been lost to urban and agricultural development, and existing populations are highly fragmented and at risk of local extirpation.

The Buena Vista Unit of the Santa Cruz Long-toed Salamander Ecological Reserve, also part of the Ellicott Slough National Wildlife Refuge (see map), is located in the rolling hills on the coast of southern Santa Cruz County where the unique and increasingly rare interface of oak woodland, coastal chaparral, grassland, willow thickets and ephemeral, or temporary, ponds combine to create ideal habitat for the SCLTS. Due to the sensitivity of the species and its habitat, this area is closed to the public.

Need for Drought Stressor Monitoring

Monitoring of SCLTS breeding ponds has revealed that in over the past three years in most areas, ponds have dried before larvae could successfully metamorphose (Figure 1). CDFW, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Resource Conservation District of Santa Cruz County have been restoring habitat, including building new breeding ponds and deepening existing ones in an effort to improve reproductive success, but it may be too little, too late.

Figure 1. Drying conditions in Buena Vista pond, May 2015. (photo by Diane Kodama)

Figure 1. Drying conditions in Buena Vista pond, May 2015. (photo by Diane Kodama)

Figure 2. Emergency salvage effort, Spring 2015. (photo by Diane Kodama)

Figure 2. Emergency salvage effort, Spring 2015. (photo by Diane Kodama)

In 2015, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) emergency salvaged 450 SCLTS larvae (Figure 2) from the Buena Vista pond on the Ellicott Unit of the SCLTS Ecological Reserve, a property jointly managed by the two agencies. These animals were going to desiccate without intervention, and there was a concern that with multiple consecutive years of no successful breeding, the population may be at risk of extirpation. With the advice of amphibian husbandry experts, SCLTS larvae (Figure 3) were reared in outdoor mesocosms (Figure 4) at CDFW and FWS facilities, and 307 metamorphs were released back to the site this summer.

Figure 3. Captive reared emergency salvaged SCLTS larvae. (photo by Diane Kodama)

Figure 3. Captive reared emergency salvaged SCLTS larvae. (photo by Diane Kodama)

Figure 4. SCLTS rearing tanks. (Photo by Diane Kodama)

Figure 4. SCLTS rearing tanks. (Photo by Diane Kodama)

Because emergency salvage is expensive and time-consuming, it is a last resort, and there’s no guarantee it will increase survival. Follow-up monitoring to determine whether this kind of effort is successful is necessary to determine whether it’s a drought-strategy CDFW and USFWS should undertake again in the future. Drought funding was used to survey for juveniles this winter once the rains began and they became surface active. Because there had been no successful breeding for several years, the only juveniles on the landscape would have to have come from the emergency salvage effort, all other individuals would be adults.

Stressor Monitoring Efforts

CDFW and partners conducted visual encounter surveys and checked pitfall trap arrays and coverboards during rainy periods in November and December.

Findings

Figure 5. Juvenile SCLTS observed in winter 2015. (photo by Robyn Boothby)

Figure 5. Juvenile SCLTS observed in winter 2015. (photo by Robyn Boothby)

Two juveniles were captured in the pitfall traps, and one was found under a coverboard (Figure 5). Therefore, a minimum of approximately 1% of the released animals are known to have survived their first summer.

Future Efforts

No future efforts using currently available drought funding are proposed; however, recognizing that one season of surveys cannot tell us about long-term survival, genetic samples were collected from a subset of released animals. This will enable us to return to the site in 3-4 years to collect genetic samples again.

CDFW

USFWS

- Diane Kodame, Refuge Manager

Ellicott Slough NWR and Salinas River NWR

510-792-0222 ext. 130