(Pescadero Creek lagoon, coastal San Mateo County)

Species / Location

Figure 1. CDFW staff measure juvenile steelhead at Pescadero Creek Lagoon on July 15, 2015. CDFW photo.

Figure 1. CDFW staff measure juvenile steelhead at Pescadero Creek Lagoon on July 15, 2015. CDFW photo.

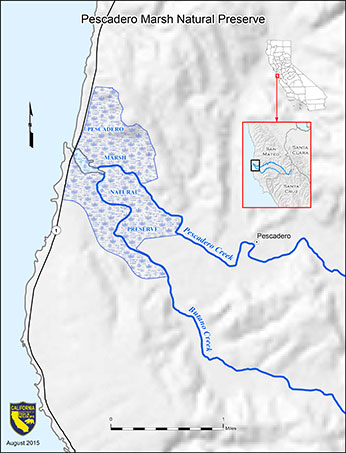

Figure 2. Pescadero Marsh Natural Preserve and Lagoon Complex located in San Mateo County, California. CDFW photo (click/tap to enlarge).

Figure 2. Pescadero Marsh Natural Preserve and Lagoon Complex located in San Mateo County, California. CDFW photo (click/tap to enlarge).

The Central Coast of California, in Santa Cruz and San Mateo Counties, supports federally threatened steelhead trout (Figure 1) and state and federally endangered coho Salmon. Both salmonid species are anadromous, meaning juvenile fish rear in freshwater, then migrate out to sea as smolts to mature to adult size before returning to freshwater streams to spawn and repeat the cycle.

Pescadero Creek forms a large watershed in coastal San Mateo County, located approximately 50 miles south of San Francisco (Figure 2). The watershed supports a large bar built estuary, or lagoon, and marsh complex at the tidal interface in the lower watershed. The lagoon develops when a sandbar forms at the creek mouth, closing the system to significant ocean influence (Figures 3A and 3B). Once the sandbar is fully formed, high tidal events or wave surges bring salt water into the lagoon, either through the sandbar or as ocean over-wash. Lagoons are well-known to be highly productive and useful habitat for migrating and rearing steelhead, as juvenile steelhead rearing in lagoons grow quickly to a large size and contribute disproportionally to the number of returning adults.

Since humans altered the hydrodynamics of the lagoon / march complex in the early 1990’s, fish kills associated with the breaching of the sandbar at Pescadero Creek lagoon have been reported 14 (out of 19) years, including 11 years in a row (1995, 1997, 2001-2011, 2013)(Figure 4). With the changed hydrodynamics, degraded water quality in the fall appears to be associated with the amount of time the lagoon is closed, the amount of time the Delta-Butano Marsh complex is inundated, and low freshwater inflow to the lagoon. Rapid mixing of water upon sandbar breach further degrades water quality by re-suspending sediment, which increases chemical oxygen demand and stirs hydrogen sulfide into water column (Sloan 2006; Smith 2009).

Recently, monitoring has shown that drought conditions on top of the altered hydrodynamics has created worse water quality conditions, inadequate for rearing salmonids, driven by low freshwater inflow from Pescadero and Butano creeks.

Figure 3A. The mouth of Pescadero Creek when it is open to the ocean. CDFW photo.

Figure 3A. The mouth of Pescadero Creek when it is open to the ocean. CDFW photo.

Figure 3B. The mouth of Pescadero Creek when it is closed, forming a bar-built lagoon. CDFW photo.

Figure 3B. The mouth of Pescadero Creek when it is closed, forming a bar-built lagoon. CDFW photo.

Figure 4. Dead juvenile steelhead observed at Pescadero Creek lagoon after breach on February 9, 2014. CDFW photo.

Figure 4. Dead juvenile steelhead observed at Pescadero Creek lagoon after breach on February 9, 2014. CDFW photo.

Need for Drought Stressor Monitoring

Typically, during years of average to above-average amount of rainfall, after sandbar closure in Central California coastal lagoons, the water column converts entirely to freshwater and water quality improves. However, without sufficient freshwater inflow from streams, water quality degrades over time. Therefore, important lagoon nursery habitat for juvenile steelhead may not function during periods of excessive drought conditions. In 2014, monitoring showed that the drought conditions also greatly limited salmonid access in and out of the Pescadero Creek watershed from the ocean because the sandbar closed the river mouth too soon. This reduced the time that juvenile salmon and juvenile and adult steelhead could outmigrate to the ocean. In order to determine the effects of drought on lagoon-rearing of juvenile steelhead, water quality monitoring and fish sampling was conducted during the summer and fall 2014.

Stressor Monitoring Efforts

CDFW measured water quality (salinity, dissolved oxygen, and temperature) throughout the water column of the lagoon/marsh complex at least once per week. This was done to provide an understanding of changes in water quality in relation to layering of freshwater (from stream inflow) on top of saltwater. Visibility in the water column varies over time due to changes in sediment and phytoplankton and was measured with a secchi disk. Additionally, water quality conditions were recorded continuously by deploying meters at the surface in five locations. Continuous monitoring provides a more detailed understanding of the rapidly changing conditions associated with sandbar breaching. Using a 100 x 6 foot beach seine, CDFW captured fish three times during the spring, summer, and fall of 2014 (Figure 5). To understand the community in the lagoon, all captured fish were identified. However, steelhead were the focus of monitoring, and data was collected to better understand their age and growth (by analyzing patterns in their scales) as well as stage in development. Catch-rates were analyzed to generally understand the population dynamics of rearing steelhead; however, these rates are known to vary with lagoon volume and schooling of fish. Other specialized survey techniques (eg mark / recapture) can provide improved view of population dynamics.

Figure 5A. CDFW staff and partners use beach seine technique to capture steelhead at Pescadero Creek lagoon on July 15, 2015. CDFW photo.

Figure 5A. CDFW staff and partners use beach seine technique to capture steelhead at Pescadero Creek lagoon on July 15, 2015. CDFW photo.

Figure 5B. CDFW staff and partners use beach seine technique to capture steelhead at Pescadero Creek lagoon on July 15, 2015. CDFW photo.

Figure 5B. CDFW staff and partners use beach seine technique to capture steelhead at Pescadero Creek lagoon on July 15, 2015. CDFW photo.

Findings

The sandbar formed early in spring 2014, the time of year when juvenile steelhead and spawned-out adults migrate to the ocean. Because the sandbar formed early, many fish were blocked from entering the ocean and stayed in the lagoon. Making matters worse for the fish in the summer, low streamflow conditions due to the drought did not allow the water column of the lagoon to convert to healthy freshwater conditions, and CDFW documented poor habitat conditions (very low dissolved oxygen concentrations and high temperatures). Algae blooms in the summer depleted oxygen levels in the lagoon during the night, making conditions in the morning difficult for fish (Figure 6). As water quality degraded, catch rates of juvenile steelhead declined throughout the closed lagoon phase.

A beach seining effort on June 19, 2014 captured 124 juvenile steelhead ranging from 4 to 10 inches in length. Scale analysis showed a high proportion of 2 year old steelhead that likely would have outmigrated to the ocean had the sandbar remained open later into spring. In addition, one spawned-out adult female steelhead blocked by the sandbar on her way to the ocean was captured. Other species observed during this sampling event included prickly sculpin, staghorn sculpin, starry flounder, threespine stickleback and tidewater goby.

On July 25, 2014, a repeat beach seining effort was conducted throughout the lagoon complex. The July sampling event only captured one steelhead. Scale analysis showed the steelhead was a 2 year old fish that had recently stopped growing likely due to stressful water quality conditions. In addition, the following other species were captured: threespine stickleback were abundant, tidewater goby were common, and prickly sculpin were present.

On October 21, 2014 another beach seining effort was conducted in the Pescadero Creek lagoon complex. This sampling effort did not capture any steelhead; however, threespine stickleback, tidewater goby, prickly sculpin, starry flounder, and topsmelt were captured during this survey.

Due to insufficient freshwater inflow or tidal mixing, the lagoon water quality degraded over the summer of 2014. The degraded water quality appeared to be driven by an excess of phytoplankton that, during periods of dark or overcast, acted to deplete the dissolved oxygen in the water column. Furthermore, low flow conditions did not supply refuge from poor water quality upstream into suitable riverine habitat. All steelhead trapped in the lagoon during summer 2014 likely perished due to stressful to lethal water quality throughout the lagoon complex. The findings in Pescadero Creek lagoon during the 2014 drought are similar to those at nearby bar built estuaries in summer 2014, San Gregorio and San Lorenzo lagoons.

Figure 6. Algae bloom in Pescadero Creek lagoon in the summer of 2014. CDFW photo.

Figure 6. Algae bloom in Pescadero Creek lagoon in the summer of 2014. CDFW photo.

Future Efforts

The sandbar conditions at the mouth of Pescadero Creek will be monitored weekly to gage salmonid access out of the lagoon during spring 2015. If the sandbar closes prematurely in future seasons (prior to a majority of smolt and adult outmigration) a fish rescue will be implemented to save trapped steelhead which likely will perish from drought conditions. A continued effort to monitor water quality throughout the dry season will be completed in summer and fall 2015 in the Pescadero Creek Lagoon Complex in order to better understand the lagoon habitat conditions for rearing salmonids during the closed period.

Regardless of a potential fish rescue, the lagoon will be sampled via a beach seine in summer and fall 2015 to answer how many steelhead utilize the lagoon habitat and how the population shifts over the dry season. The number of steelhead in the lagoon will be estimated with specialized survey techniques..

References

- Sloan, R. M. 2006. Ecological investigations of a fish kill in Pescadero Lagoon, California. Master’s Thesis. San Jose State University, San Jose, California.

- Smith, K. A. 2009. Inorganic chemical oxygen demand of re-suspended sediments in a bar-built lagoon. Master’s Thesis. San Jose State University, San Jose, California.