Species and Location

Steelhead/Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) are a salmonid species inhabiting coastal streams from Alaska to Baja California. O. mykiss exhibit two life history forms: resident (Rainbow Trout) which live their entire lives in freshwater streams and anadromous (steelhead) which migrate to the ocean and return to freshwater to spawn. Due to persistent decline in southern O. mykiss populations, the Southern California steelhead distinct population segment is a federally listed endangered species and a candidate for California state listing.

Mission Creek and tributary Rattlesnake Creek run from the Santa Ynez mountains through the city of Santa Barbara, California. Southern California steelhead/Rainbow Trout have historically occupied the Mission Creek watershed, including a substantial migration of winter-run steelhead prior to construction of dams in the 1800s. Despite human alteration of Mission Creek, a small population of trout have persisted. In 1999, 70-80 O. mykiss (likely residents) were observed in a 1200m section of creek. Between 2000 and 2007, eighteen steelhead were observed in Mission Creek, as were several smolts, indicating successful anadromous spawning. Despite recent efforts to restore passage, habitat remains degraded after years of urbanization.

Mission Creek watershed is also home to Threespine Stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus), two-striped garter snake (Thamnophis hammondii), and California red-legged frog (Rana draytonii). Current O. mykiss presence in the watershed is limited to a small Rattlesnake Creek population and a few individuals residing above the limits of anadromy on Mission Creek. Mission and Rattlesnake Creeks are monitored regularly by California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) staff, with a focus on O. mykiss conservation.

Need for Drought Stressor Monitoring

Mission Creek and Rattlesnake Creek may go dry in the city of Santa Barbara even during normal water years. Reliable perennial habitat is limited to the foothills high in the watershed. In December 2019, road maintenance activities by a contractor working for Southern California Edison introduced a significant amount of rock and sediment into the upper reaches of the creek, upsetting crucial O. mykiss habitat downstream. Water demands within the basin have likely worsened this problem and ongoing drought conditions leave very little refugia habitat for trout to survive over summer. O. mykiss in this watershed are particularly vulnerable to drought, as the loss of even a few fish represents a large portion of the population. Preserving O. mykiss populations in the short term requires proactive monitoring and creative relocation solutions.

Stressor Monitoring Efforts

CDFW staff surveyed Mission Creek during winter and spring beginning at the estuary and moving upstream to a total natural barrier to anadromy, approximately six miles upstream. A 2.3 mile walking reach on Rattlesnake beginning at the Mission Creek confluence and ending at a total natural barrier to anadromy was surveyed year-round. During surveys, staff identify wetted sections, habitat availability and the presence of fish as well as identifying stranded trout in need of relocation. Flow and water quality were measured in 2022 at the Mission Creek confluence and just downstream of Las Canoas Rd (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CDFW monitoring sites and walking reaches (Mission Creek and Rattlesnake Creek) within the Mission Creek watershed (outlined in dark green). Both water quality sites on Rattlesnake had dried by June 2022, as had the lower water quality site on Mission Creek.

Figure 1. CDFW monitoring sites and walking reaches (Mission Creek and Rattlesnake Creek) within the Mission Creek watershed (outlined in dark green). Both water quality sites on Rattlesnake had dried by June 2022, as had the lower water quality site on Mission Creek.

To monitor changes in water temperature, a continuous temperature/dissolved oxygen logger was deployed in a habitat unit containing trout on Mission Creek. A temperature logger was deployed at the Old Mission Dam within the Santa Barbara Botanic Gardens. In summer of 2022, another temperature/dissolved oxygen logger was deployed approximately 0.75 miles upstream of the Santa Barbara Botanic Gardens in a potential relocation habitat unit.

Findings

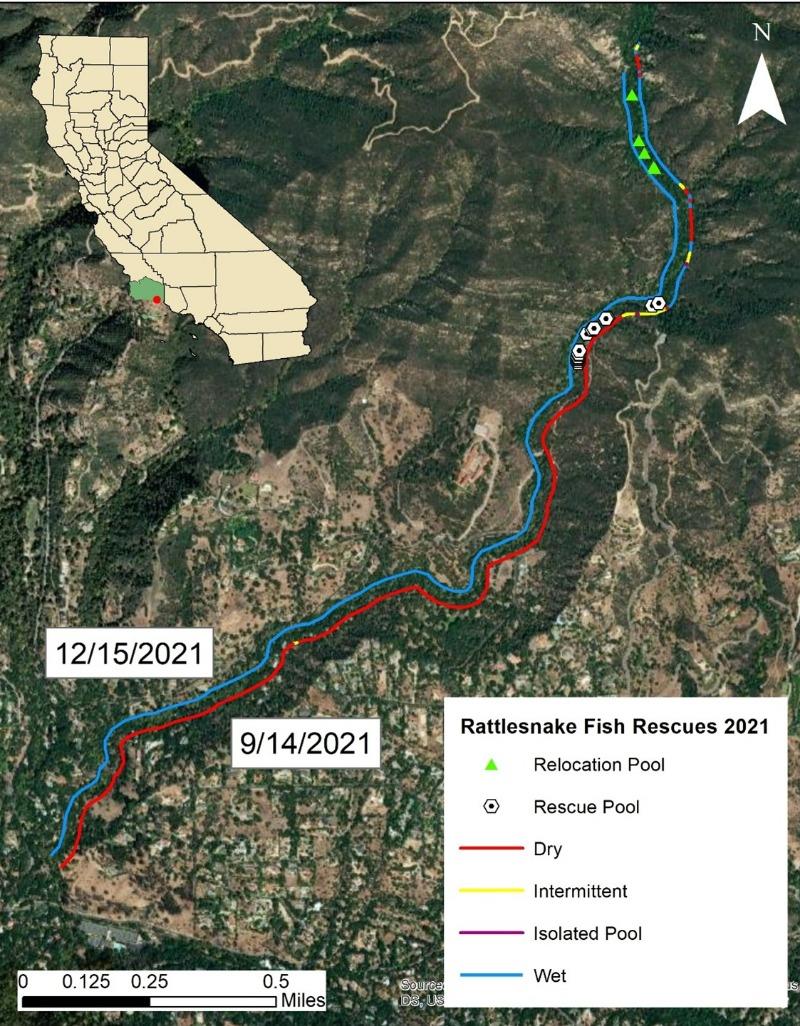

Rattlesnake Creek contains a small O. mykiss population (36 individuals were observed in a summer 2021 CDFW snorkel survey). The creek contracted severely under drought conditions in summer 2021 (Figure 2). Only 17.2% (0.39 miles) of the walking reach was wetted during September 2021, including several extended intermittent sections which provided little to no suitable fish habitat. To prevent the loss of biological resources as the creek contracted, three summer 2021 relocations were conducted by CDFW (Figure 3). Many of the units rescued in 2021 required rescue again in summer 2022 as fish upstream had moved downstream in winter and became stranded.

Figure 2. Rattlesnake Creek looking upstream from the Mission Creek confluence, 12/15/21 (left) and 6/23/22 (right).

Figure 2. Rattlesnake Creek looking upstream from the Mission Creek confluence, 12/15/21 (left) and 6/23/22 (right).

Figure 3. A map of the Rattlesnake Creek walking reach at its driest point during summer 2021 (9/14, lower line) and following rain (12/15, upper line). 2021 rescue and relocation units from fish relocations during summer 2021 are shown.

Figure 3. A map of the Rattlesnake Creek walking reach at its driest point during summer 2021 (9/14, lower line) and following rain (12/15, upper line). 2021 rescue and relocation units from fish relocations during summer 2021 are shown.

Of the lower 4 miles of Mission Creek, 2.4 miles had dried completely by April 2022. Although further drying occurred, this section of creek was not surveyed throughout summer due to its lack of suitable habitat. As this section of creek is urban and highly channelized, it does not provide ideal habitat even when wetted. However, the lengthy dry section disconnects upstream habitat from the ocean during summer.

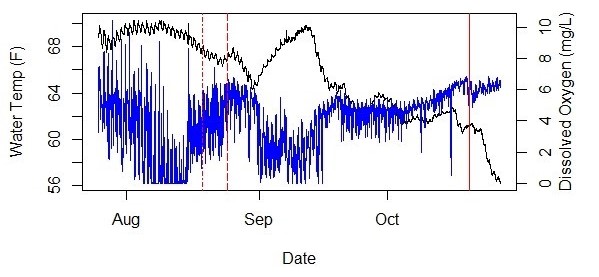

A summer 2021 snorkel survey of Mission Creek surveyed 4.6 miles of Mission Creek (48 habitat units) and found 2 O. mykiss. These individuals were believed to be the last trout living in Mission Creek. Monitoring of upper Mission Creek identified very few suitable habitat units and those containing trout recorded severely depressed levels of dissolved oxygen in summer, although water temperatures remained in the 60-70F range. With limited options for relocation within the watershed, the O. mykiss were forced to withstand these conditions until they were improved with a late October rain. Encouragingly, both fish survived summer 2021 despite incredibly poor conditions, including several nights when dissolved oxygen fell below 1 mg/L. The fact that both O. mykiss were confirmed to survive these conditions for several months indicates a hardiness in southern California O. mykiss that may be beneficial to surviving drought conditions.

In summer 2022, an O. mykiss was observed in a unit known as Fern Falls, upstream of the two previously identified fish, although water quality was poor. With CDFW input, several community members set up a water release directly into Fern Falls to maintain water volume in the unit. Water releases took place 12-5 am nightly, with the hope of raising dissolved oxygen and lowering water temperature. Water was sprayed at a rock wall upstream to aerate and dechlorinate it before it flowed to the pool. The water release was effective in raising the dissolved oxygen (DO) and decreasing water temperature while active, but dissolved oxygen in the unit crashed between sunset and the nightly start time of the water release. To prevent a temporary drop in DO, CDFW staff built a low-cost battery-operated aeration system to sustain DO levels between photosynthesis-driven oxygen production and the water release (Figure 4). The aerator was capable of circulating 500 gallons/hr by spraying water through the air to cool and aerate it. Logger data indicated that, while active, the aerator raised DO by approximately 2 mg/L (Figure 5). Due to the improvement in habitat quality, the fish located downstream were relocated to the aerated pool.

Figure 4. Deployable aerator operating in Fern Falls pool, Mission Creek, Santa Barbara.

Figure 4. Deployable aerator operating in Fern Falls pool, Mission Creek, Santa Barbara.

Figure 5. Water temperature (black) and dissolved oxygen (blue) in the Fern Falls Pool on Mission Creek where two O. mykiss were relocated in summer 2022. CDFW staff deployed an aerator to raise nighttime DO levels (left red line) and relocated fish (middle red line). The water release operated until 10/19/22 (right red line). Positive impacts of the aerator are illustrated between the left and middle lines – a drop in DO after deployment can be attributed to atmospheric conditions (heat wave) at the time.

Figure 5. Water temperature (black) and dissolved oxygen (blue) in the Fern Falls Pool on Mission Creek where two O. mykiss were relocated in summer 2022. CDFW staff deployed an aerator to raise nighttime DO levels (left red line) and relocated fish (middle red line). The water release operated until 10/19/22 (right red line). Positive impacts of the aerator are illustrated between the left and middle lines – a drop in DO after deployment can be attributed to atmospheric conditions (heat wave) at the time.

Future Efforts

In partnership with ongoing restoration projects and barrier removals in the basin, we hope that relocation and efforts to maintain refugia habitat on Mission and Rattlesnake creeks will result in survival and successful 2022-23 spawning in these small O. mykiss populations. Staff will continue to monitor these streams throughout winter and summer 2023. If drought conditions persist, additional relocations will likely be necessary to preserve these populations.