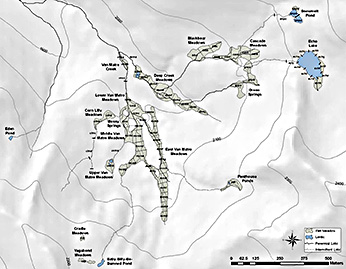

Echo Lake Basin, Trinity Alps Wilderness Area, Shasta-Trinity National Forest, Trinity County

Species / Location

(click/tap to enlarge)

(click/tap to enlarge)

Echo Lake basin is located in the Trinity Alps Wilderness Area, Trinity County, CA (see map). The basin is a medium, 342 hectare (ha) sized glacial cirque encompassed by steep jagged peaks reaching elevations up to 2497 m, among the highest in the Klamath Province. Prior to trout stocking as early as the 1800's, this area was fishless. Native fauna have few permanent habitats that are free of non-native fish in the Trinity Alps Wilderness Area. Previous Cascades frogs studies have shown that removal of introduced non-native trout from high-mountain lakes resulted in an increase in native frog population densities (Pope 2008). Similar research in this area also demonstrated that trout introductions facilitated the expansion of the Aquatic Gartersnake (Thamnophis atratus), an opportunistic fish specialist predator that will also prey upon amphibians.

Drought funding was used to expand the area and intensity of this project to facilitate the removal of non-native Eastern Brook Trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) and to monitor the response of native fauna to the habitat restoration efforts. The restoration project is expected to increase the availability of fishless aquatic habitats by a minimum of 77% of the total available perennial waters within the Echo Lake basin. The resulting increase of fishless perennial habitats will restore wetland resilience for native aquatic fauna facing a drier climate future.

Echo Lake basin has multiple seasonal wetland patches, which are vulnerable to drought and climate change-induced drying due to decreasing snowpack trends. Echo Lake is small (1.3 he), shallow (<6 m deep), has simple bathymetry, and very little spawning habitat. These conditions make it an ideal location for fish removal with a high likelihood of success in a rapid timeframe. The 1.3 kilometers streams containing non-native trout are also small, shallow, and become isolated during the fall making them ideal for electrofishing which has proved to be a very effective method for fish removal in similar restoration projects in high-elevation basins of the Sierra Nevada range such as the Stella Lake Restoration for the Sierra Nevada Yellow-legged Frog. Restored perennial wetlands will provide refugia for at least three native Species of Special Concern amphibians that are highly susceptible to non-native fish predation: the Cascades Frog (Rana cascadae; Figure 1), also a species petitioned for federal listing under the Endangered Species Act, the Coastal Tailed Frog (Ascaphus truei), and the Southern Long-toed Salamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum sigillatum).

Need for Drought Stressor Monitoring

Snowpack data from the California Department of Water Resources for the month of April, 2015 in the Echo Lake basin area show the study area has undergone significant snowpack reduction in recent years: 72% (2012), 16% (2013), 9% (2014), and 3% (2015). Amphibians with aquatic life stages, such as the ones targeted for this project, are susceptible to drought-related premature drying of aquatic breeding habitats that desiccate tadpoles before they can metamorphose into adult forms that can survive on land (Figure 2). The amphibian, reptile, and fish populations in Echo Lake basin have been intensively monitored over the past 12 years, creating a unique opportunity to assess the impacts of restoration in this ecosystem as non-native fish are removed. This project is the first of its kind in the Klamath Bioregion wilderness areas and will provide a model for future habitat restoration of local imperiled amphibians based on management recommendations from CDFW’s approved Aquatic Biodiversity Management Plans. Land managers have current interest in regional sub-alpine wetland restoration and will be able to refer to this model project as a tool for future restoration of key amphibian habitats in the Klamath Bioregion which presently contains hundreds of lakes and streams with non-native predatory trout.

Figure 1: Adult Cascades Frog at Echo Lake. Photo J. Garwood.

Figure 1: Adult Cascades Frog at Echo Lake. Photo J. Garwood.

Figure 2: Dry Cascades Frog breeding pond. Photo Michael van Hattem.

Figure 2: Dry Cascades Frog breeding pond. Photo Michael van Hattem.

Restoration and Stressor Monitoring Efforts

The addition of two Scientific Aids was necessary to complete summer surveys. Beginning in July 2015, California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) personnel began the removal of introduced Eastern Brook Trout populations from upper Echo Lake using a combination of gill nets, electrofishing and seines (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3: Removing Eastern Brook trout from gill nets at Echo Lake. Photo J. Garwood.

Figure 3: Removing Eastern Brook trout from gill nets at Echo Lake. Photo J. Garwood.

Figure 4: Electro-fishing non-native trout. Photo J. Garwood.

Figure 4: Electro-fishing non-native trout. Photo J. Garwood.

To compare population estimates, survival rates, and site fidelity relative to an existing long-term dataset collected prior to fish removal, CDFW conducted visual encounter surveys for all amphibian and reptile species throughout the restoration area and employed mark-recapture methods of Cascades Frogs (Figure 5) and Common and Aquatic Gartersnakes (Figure 6).

Figure 5: PIT tagging Cascades frog for long-term population monitoring. Photo A. Macedo.

Figure 5: PIT tagging Cascades frog for long-term population monitoring. Photo A. Macedo.

Figure 6: Aquatic Gartersnake population monitoring. Photo A. Macedo.

Figure 6: Aquatic Gartersnake population monitoring. Photo A. Macedo.

Findings

CDFW removed a total of 674 Eastern Brook Trout from Echo Lake basin including 331 from Echo Lake and 342 from over a mile of stream channels during the summer of 2015. The vast majority of the adult fish population was removed with only trout fry being captured by the end of the summer. Five amphibian and garter snake censuses were completed throughout the summer across five habitat patches. We captured and marked a total 522 Cascades Frogs and counted 258 larvae. However, other amphibian species sightings were rare, including only one observation of a Southern Long-toed Salamander egg mass and only two larvae. Additionally we observed one Coastal Tailed Frog, four adult Western Toads (Anaxyrus boreas), and one Western Toad egg mass. Given this was the first summer of this fish removal restoration project, we predict observations of rare amphibians to increase, especially in habitats formally occupied by trout.

In addition to amphibians, we captured a total of 26 Aquatic Gartersnakes and 21 Common Gartersnakes (Thamnophis sirtalis). All Aquatic Gartersnakes were found in habitats containing fish, and we predict once fish are removed these snakes will either switch to eating frogs or move entirely out of the area since they are a fish foraging specialist.

Future Efforts

CDFW staff will maintain the database and analyze data during the winter and spring of 2016, in which time a subsequent progress report will be issued. We will also be preparing for the 2016 summer field season.

References

-

Pope, K.L. 2008. Assessing changes in Amphibian Population Dynamics Following Experimental Manipulations of Introduced Fish. Conservation Biology 22(6):1572-1581.