(Monterey and San Luis Obispo counties)

Species / Location

Figure 1. Adult steelhead in San Luis Obispo Creek (San Luis Obispo County). CDFW photo.

Figure 1. Adult steelhead in San Luis Obispo Creek (San Luis Obispo County). CDFW photo.

Central California coastal rivers and streams are typically smaller than those in northern California and the Central Valley, due to their smaller watersheds and varied flow patterns. South-Central California Coast steelhead, present in many of these streams, are listed as threatened under the Federal Endangered Species Act (Figure 1). Historically, these fish were more abundant but over the last several decades, populations have decreased due to a variety of impacts (e.g. dam construction, water management, habitat degradation due to land use practices, and stream diversions). These impacts occurred during a time when this region of the state was being settled and when California experienced a wetter climate. The normal climate pattern for California is drier than what occurred for the last 150 years (Ingram 2013).

Need for Drought Stressor Monitoring

Water Year 2014 [WY 2014 (October 1, 2013 to September 30, 2014)] was one of the driest years on record in California and followed two drought years. Due to the severity of the drought, the Governor declared a state of emergency and established water conservation and monitoring measures.

Stressor Monitoring Efforts

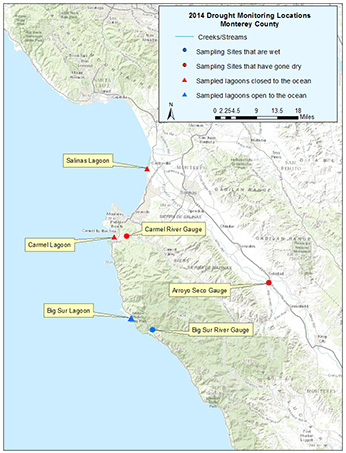

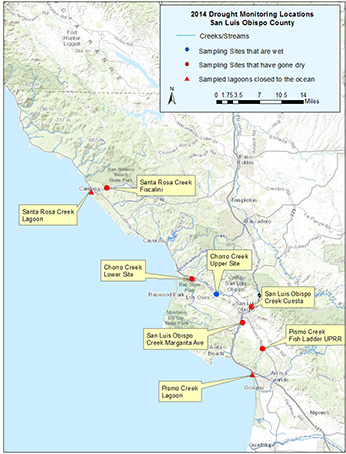

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) began conducting drought monitoring in Central California coastal streams of Monterey and San Luis Obispo County on a weekly basis starting on March 3, 2014. This summary captures monitoring through November 30, 2014. At each monitoring site, data collection included flow, dissolved oxygen, water temperature, stream condition, and connectivity to the lagoon (where appropriate). Visual observations at each site were also made to document water clarity and algae growth. In addition, USGS stream gauge readings were recorded for the Big Sur, Carmel, and Salinas rivers. In Monterey County, six sites on four rivers were monitored (see Figure 2). In San Luis Obispo County, eight sites on four streams were monitored (see Figure 3).

Figure 2. Drought monitoring locations in Monterey County in 2014

Figure 3. Drought monitoring locations in San Luis Obispo County in 2014.

Figure 3. Drought monitoring locations in San Luis Obispo County in 2014.

Findings

In Monterey County, the lagoons of the Salinas and Carmel rivers typically open to the ocean during the winter and spring. This year, they remained closed, preventing access for adult steelhead into these watersheds for spawning and blocking juvenile emigration to the ocean. It is worth noting that even the Big Sur River, which typically remains open throughout the year, became intermittently disconnected with the stream during low tide events. In addition, as the drought persisted, all of the rivers either dried up in at least one section or had significantly reduced flow upstream of the lagoons, blocking juvenile steelhead access to the lagoons for rearing.

In San Luis Obispo County, lagoons on each of the four monitored streams remained closed as well, preventing adult steelhead immigration and juvenile emigration. With the exception of the Upper Chorro Creek monitoring site, where flow persisted throughout the year, all other monitoring sites in the county either had no flow (disconnected pools) or dried up during the WY 2014 monitoring period. There was no flow recorded at the Pismo Creek site and the disconnected pool dried at the end of April. At both of the San Luis Obispo Creek sites, flow ceased in May; the Lower San Luis Obispo Creek site completely dried in May, and the upper site completely dried in June. The Lower Chorro Creek site’s flow ceased in July, leaving isolated pools until the end of November. Santa Rosa Creek stopped flowing at the end of July and completely dried in early October. Habitat availability was significantly reduced in the streams as flow ceased, likely resulting in some fish mortality and/or predation by birds and small mammals, thereby reducing population recruitment. There was no observation of dead fish as a result of stream flow becoming disconnected or completely drying up, so no mortality was documented. Seeing no dead fish as a result of a stream drying up is not unexpected as dead fish can be quickly eaten by scavengers.

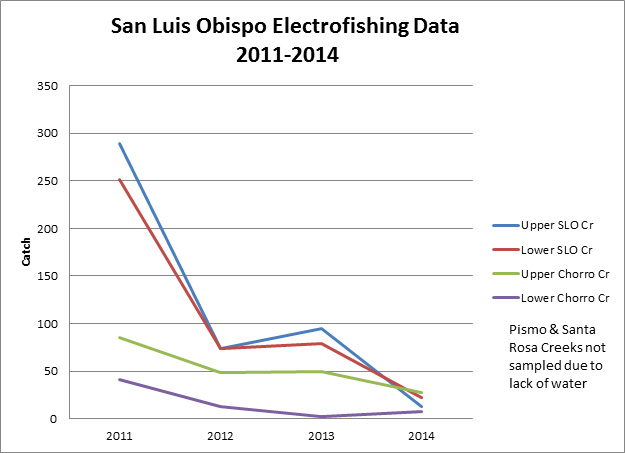

Annual electrofishing results for Chorro and San Luis Obispo Creeks, conducted since 2011 at established sites, show an overall decline in catch since the start of the drought (see figure 3). (There are no results for Santa Rosa and Pismo Creeks as designated electrofishing sites have not had water since 2011.) This decline is likely in response to drought conditions and signifies a potentially significant loss of recruitment into the population due to lack of successful spawning, reduced habitat though isolated and disconnected habitat, and significant dry back of streams.

Figure 3. Juvenile steelhead abundance information in creeks within San Luis Obispo County.

Figure 3. Juvenile steelhead abundance information in creeks within San Luis Obispo County.

Future Efforts

In these two counties, drought stressor monitoring has enabled the longest term data collection, documenting river and stream responses to severe climate conditions. These data are valuable in terms of not only documenting stream flow conditions during a severe drought, but also provide context for potential stream condition response as global warming affects a drier climate over time. This effort is also valuable in identifying stream flow as a critical limiting factor for steelhead, specifically as it relates to adult immigration, juvenile emigration, successful spawning and rearing, and population recruitment. Coupled with the competing human water demands, steelhead populations are not expected to persist overtime if all life stages of steelhead continue to be impacted by lack of flow, especially during drought conditions. There is a need to conduct instream flow studies on steelhead streams in Monterey and San Luis Obispo counties to quantify minimum instream flow thresholds that are needed to improve conditions for steelhead. Once revised instream flows are implemented by the State Water Resources Control Board, having a water master for each steelhead-bearing water would help to ensure that there is sufficient water for steelhead populations to persist into the future.

References

- Ingram, B.L. and B. L. Ingram. 2013. The West Without: Water What Past Floods, Droughts, and Other Climatic Clues Tells Us About Tomorrow. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.