Species found on soft sediment substrate include rose-sand anemones, giant red sea cucumbers, various flatfish, and brittle stars. (CDFW/MARE photo)

Species found on soft sediment substrate include rose-sand anemones, giant red sea cucumbers, various flatfish, and brittle stars. (CDFW/MARE photo)

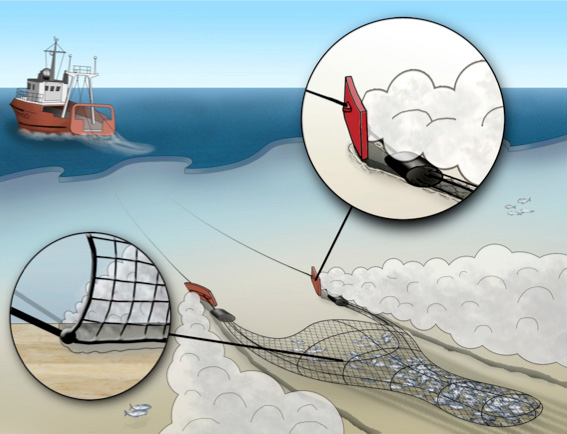

Conceptual drawing of bottom trawling impacts on seafloor habitats. The net and metal plates drag along the seafloor. (USGS image by Ferdinand Oberle)

Conceptual drawing of bottom trawling impacts on seafloor habitats. The net and metal plates drag along the seafloor. (USGS image by Ferdinand Oberle)

Conserving ecosystem health and diversity

The MLMA highlights the connection between healthy fisheries and healthy ecosystems and underscores the importance of considering the impact of a fishery on the ecosystem. To preserve the function of an ecosystem, impacts from non-fishery factors such as climate and environmental change should be considered. This reflects a broader recognition worldwide of the need for holistic approaches to fisheries management. However, ecosystems are complex and in constant flux, and the specifics of how they function are not well understood. Making management decisions in this context can be challenging, even in data-rich environments.

Fluctuations in environmental or ecological conditions can have significant impacts on the abundance of target species. The development of ecosystem indicators can be a valuable tool to help ensure that management measures can track and respond to such changing conditions. The discussion of HCRs in Chapter 5 and Appendix J addresses the development and use of ecosystem indicators.

The section below focuses on the impacts of fishing on the ecosystem and provides guidance on ecosystem information to integrate into ESRs and FMPs and how EBFM approaches can be applied using available information and tools.

An ecosystem-based approach to managing fisheries

EBFM requires that ecosystem impacts be considered broadly and consistently in fisheries management. It is a departure from traditional single-species management, in which management decisions consider each species in isolation and do not account for ecosystem dynamics, such as interactions with other species, effects of environmental changes or pollution, and impacts of other stresses on habitat and water quality. While there is widespread recognition of the importance of taking a holistic approach to fisheries management, implementing such an approach has proven difficult. As with other aspects of fisheries management, a lack of data and information can limit understanding of biological and human dynamics, but need not prevent taking action based on general principles and use of available data and knowledge. It is possible to apply the principles of EBFM when making management decisions even in the absence of the data underpinning complex models of entire ecosystems.

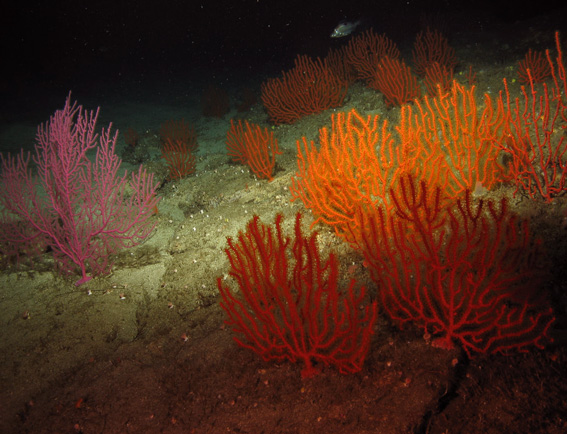

Gorgonians are delicate soft corals that grow on the seafloor, providing important habitat for fish and other marine life. (CDFW/MARE photo)

Gorgonians are delicate soft corals that grow on the seafloor, providing important habitat for fish and other marine life. (CDFW/MARE photo)

Kelp bass in a kelp forest. (Greg Amptman/Shutterstock photo)

Kelp bass in a kelp forest. (Greg Amptman/Shutterstock photo)

Identification of species that play key roles in the ecosystem

One of the goals of the MLMA is to preserve the ecosystem functions that are essential for sustaining commercial and recreational fishery species over the short- and long-term (§7050(opens in new tab)). While the literature on ecosystem function continues to evolve, one practical approach to preserving these functions has been to identify the species that play key roles within the ecosystem and their trophic levels, and to ensure that these species are managed sustainably. Conserving the species that play these key roles provides a way to protect the ecosystem functions and services these species play, both directly and indirectly.

Types of key species and their ecosystem roles include the following:

- Keystone species are those that have been shown or are expected to have community-level effects that are disproportionate to their biomass.

- Foundational, structural, or biogenic species are habitat-forming species (e.g., oyster beds, sponges, corals).

- Basal prey species include small pelagic(opens in new tab) forage species such as krill, Pink Shrimp, Pacific Herring, squid, anchovies, and sardines. The high natural variability in the dynamics of these species can have large impacts on their predators and prey.

- Top (or apex) predators are predators for which the removal of a small number of the species could have large or disparate ecosystem effects.

Changes to the structure of these species’ populations, which may include changes to the abundance, size structure, genetic structure, or distribution, should be monitored, and management measures should strive to maintain appropriate population structures for species in these roles to the extent possible. For example, the Commission has adopted a policy specifically for the management of forage fish(opens in new tab), which play a major role in the California Current Ecosystem (CCE)(opens in new tab) (Commission 2012). Forage fish are small pelagic organisms, such as Northern Anchovy, Pacific Sardine, Market Squid, and Pacific Herring that provide an important food source for larger marine organisms. They fill the critical ecosystem role of transferring energy from planktonic plant and animal life to larger fishes, marine mammals, and seabirds. Environmental conditions and climate regimes can have major effects on forage fish distribution and abundance.

Forage fish serve an important ecosystem role as food for seabirds, marine mammals, and larger fish. (Kojihirano/Shutterstock photo)

Forage fish serve an important ecosystem role as food for seabirds, marine mammals, and larger fish. (Kojihirano/Shutterstock photo)

Consider management strategies with multiple control measures

Recent studies have found that an integrated management strategy, which is defined as one that involves a combination of management measures (such as size limits, gear restrictions(opens in new tab), spatial restrictions, effort restrictions, and quotas) to control fishing, is more likely to achieve EBFM objectives than those strategies that rely on a single restriction (Fulton et al. 2014). This is because while a single management measure may maximize catch in a single-species management context, different management controls may provide protection to different aspects of ecosystem function. For example, size limits or restrictions on mesh sizes might help to preserve more natural size and age structures in a population, so that the target species can continue to fulfill its ecological role (i.e., as predator or prey for other species in the ecosystem). Gear and spatial restrictions may reduce habitat and bycatch impacts. Seasonal restrictions may not only allow the target species to spawn, but also reduce bycatch of the species that feed on spawn during that time period. In this way, strategically employing a wider range of management measures may have benefits to the ecosystem as a whole.

Conduct Ecological Risk Assessments to understand which ecological links are most critical

The inherent variability, complexity, and uncertainty in ecological systems makes a complete understanding of ecosystem dynamics impossible. Nevertheless, the MLMA requires that management be based on the best available scientific information (§7050(b)(6)(opens in new tab)). Some experts have suggested that even a qualitative understanding of these relationships, such as an understanding of “who eats whom”, can be used to make decisions that account for ecosystem interactions (Patrick and Link 2015). In addition, there are analytical tools available, such as the ERA (described in Chapter 2), that can help identify which processes are most likely to impact ecological function, even when only qualitative or semi-quantitative information is available. Understanding the main drivers and major uncertainties of a system is important. This allows precautionary approaches to be applied only where needed, and can help to identify areas for future research.

Inquiries and recommended actions:

- Has the ecological role of the target species been identified? Does the target species play a key ecosystem role as defined above?

- Describe what is known about the trophic level, predators, and prey of the target stock throughout its life cycle.

- If the ecological role of the target species has not been identified, consider prioritizing the collection of this information as a research need in ESRs and FMPs.

- Is the target species a basal prey species?

- If so, additional consideration may be necessary to comply with the Commission’s Policy on Forage Species (Commission 2012(opens in new tab)).

- Has an ERA been conducted for the target species?

- If so, identify any major ecological threats, and consider applying management measures to mitigate those threats.

- If not, consider conducting an ERA for the fishery.

- Have the major areas of uncertainty in ecosystem dynamics been identified?

- If not, seek to identify the areas of uncertainty.

- If not, consider additional precaution to reflect the level of uncertainty.

- Are multiple control measures in place that may help to achieve EBFM objectives?

- If not, consider what, if any, additional measures may be needed to create an integrated management strategy as defined above.

- Has there been an assessment of how the target stock is likely to be impacted by changing environmental or ecological conditions?

- If not, consider the collection of EFI that can inform the development of environmental or ecological indicators.

- As indicators are developed, integrate into MSE analyses and HCRs as appropriate.

Photo at top of page: Schooling fish. (NOAA photo by Adam Obaza)