Entosphenus tridentatus

Species Description

Figure 1: Pacific lamprey. USFWS 2012.

Figure 1: Pacific lamprey. USFWS 2012.

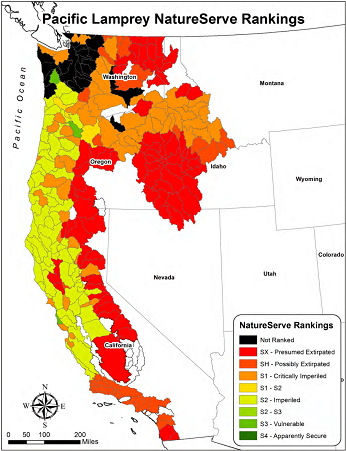

Figure 3: Calculated NatureServe risk rankings for Pacific Lamprey. USFWS 2019. (click/tap to enlarge

Figure 3: Calculated NatureServe risk rankings for Pacific Lamprey. USFWS 2019. (click/tap to enlarge

Lampreys are jawless fishes and considered part of an ancient assemblage of Agnathan fishes dating back to the Ordovician Period; about 450 million years ago. Of the Agnathans, only hagfishes and lampreys still remain today. Pacific Lamprey Entosphenus tridentatus is one of six species within this genus. Pacific Lampreys are eel-like in form and anadromous, using both fresh water and marine habitats to complete their life cycle. Adult Pacific Lampreys are parasitic and well-known for the sucker-like disc and three cuspid teeth used to cling to other animals to feed. Pacific Lampreys are unique from other fishes in that they lack paired fins, scales, bones, vertebrae, and a swim bladder. Swimming is performed by lateral undulations of the body from nose to tail (anguilliform) or by clinging on to surfaces and bursting forward (Figure 1).

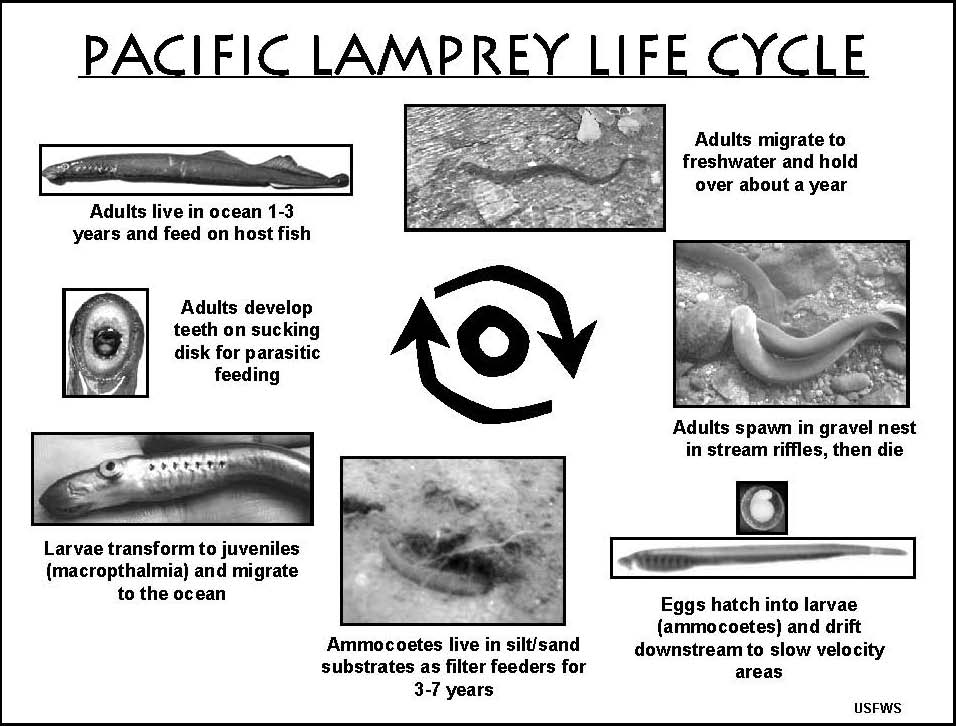

After about 1-3 years in the ocean, adult Pacific Lampreys migrate to freshwater to spawn. Like Pacific salmon, adult Pacific Lamprey are semelparous, meaning adults have one spawning event, then die to release marine nutrients into the stream. They also stop eating during migration and must rely on body fat reserves for energy. Some individuals migrate at a fairly steady rate over a period of two to four months, moving upstream in waves at night (Moyle et al. 2015). Adults can spawn right away; building a gravel nest by lifting and digging. Another life history strategy observed in the Klamath River watershed is to hold in freshwater for about a year until maturing, then spawn in the spring (Parker 2018). The best temperature range for embryonic development is between 10⁰ C and 18⁰ C. It has been observed that temperatures above 22⁰ C increase the risk for morphological abnormalities (Meeuwig et al. 2005). The eggs hatch into the ammocoete larvae in about 19 days, and drift downstream to slow velocity areas with sandy bottoms. Ammocoetes live in the silt, sand and detritus substrates as filter feeders for 3-7 years, then transform to juvenile macropthalmia. At this stage, the animal migrates downstream to the ocean and the cycle begins again (Figure 2).

Figure 2: General life cycle of Pacific Lamprey. USFWS 2019.

Figure 2: General life cycle of Pacific Lamprey. USFWS 2019.

Distribution

Pacific Lampreys Entosphenus tridentatus were historically abundant along the West Coast of North America, however, their abundance declined and distribution contracted throughout Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and California (Luzier et al 2009). The ecological and climatic characteristics of areas in California that support Pacific Lamprey populations vary considerably; "from cool mountain slopes to moist coastal drainages to arid southern chaparral" (Goodman and Reid 2012). The historical range extended throughout anadromous waters; into high elevation streams of the Sierras and tributaries, to the Sacramento River as well as coastal salmon and steelhead streams. Pacific Lamprey are extirpated in parts of Southern California and above dams and other passage barriers. Since the 2012 agreement and assessment, data availability has increased in California and a distribution database is maintained.

Species Status

Pacific Lamprey is a California State Species of Special Concern. Under this designation, the status was identified by (Moyle et al. 2015) as “moderate concern” since the species still occupies much of its native range, but at much smaller numbers. Evidence suggests that large declines may have occurred in the last 50 years. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has also designated Pacific Lamprey as a Species of Concern.

Threats

A modified NatureServe ranking model (Master et al. 2012) was used to rank a series of population demographic and threat factors to calculate the relative risk of extirpation of Pacific Lampreys at a specific geographic scale (USFWS 2019). In California, rankings range from presumed extirpated, to possibly extirpated, to critically imperiled, to imperiled, to vulnerable (Figure 3). The predominant threats identified and reported in the Pacific Lamprey Assessment (PDF) within the California region watersheds are dewatering and flow management, and passage barriers (USFWS 2019).

Conservation and Management

Native American tribes of the Pacific Northwest and California regard Pacific Lamprey as a highly valued resource, both for their ecological and cultural importance, and for food and spiritual sustenance. In July 2008 the four treaty tribes within the Columbia River basin released a draft of the Tribal Pacific Lamprey Restoration Plan (Tribal Plan) for the Columbia River Basin. In 2004 and 2008, the treaty tribes held summits with managers from federal agencies that hold the responsibility for managing fish and fish habitat. The tribal leaders expressed the urgency to begin implementing Pacific Lamprey restoration using their authority. The agencies agreed to implement the Tribal Plan and include the Tribal Plan into the USFWS’s Rangewide Plan and Best Management Practices for Pacific Lamprey. The Lamprey Technical Workgroup is a technical advisory committee of the Conservation Agreement for Pacific Lamprey in Alaska, Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and California.

Since the completion of the original Conservation Measures Assessment for California, California partners have accomplished many restoration projects to benefit Pacific Lamprey. For example, passage assessments and monitoring, large and small dam removals, and fish ladder modifications. But more work continues through outreach and education to further enhance protection measures during dewatering and dredging activities.

References

- Goodman, D.H. and S.B. Reid. 2012. Pacific Lamprey (Entosphenus tridentatus) Assessment and Template for Conservation Measures in California. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Arcata, CA. 117 pp.

- Master, L.,D. Faber-Langendoen, R. Bittman, G.A. Hammerson, B. Heidel, J. Nichols, L. Ramsay, and A. Tomaino. 2009. NatureServe conservation status assessments: factors for assessing extinction risk. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia.

- Meeuwig, M.H., J.M. Bayer, and J.G. Seelye. 2005. Effects of temperature on survival and development of early life stage Pacific and western brook lamprey. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 134:19-27.

- Moyle, P.B., R.M. Quinones, Katz, J.V, and J. Weaver. 2015. Fish species of special concern in California, Sacramento: California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

- Parker, K.A. 2018. Evidence for the genetic basis and inheritance of ocean and river-maturing ecotypes of Pacific Lamprey (Entosphenus tridentatus) in the Klamath River, California. Thesis and projects 179.

- USFWS. 2019. Pacific Lamprey Entosphenus tridentatus Assessment, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, February 1, 2019.

Other Agency Information

News