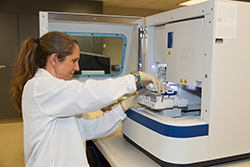

Erin loads evidence samples onto the Applied Biosystems 3500xl Genetic Analyzer in order to visualize their DNA profiles.

Erin and her husband, Jeff Rodzen, a fisheries geneticist for CDFW, have two children, 4-year-old Ryan and 9-month-old Reagan.

Erin and her husband, Jeff Rodzen, a fisheries geneticist for CDFW, have two children, 4-year-old Ryan and 9-month-old Reagan.

Erin competes in dressage aboard her horse Grande.

Erin Meredith is a senior wildlife forensic specialist. With 18 years at CDFW’s Wildlife Forensics Laboratory (WFL), Erin is the senior member of the four-person scientific team that conducts DNA analysis, species identification and other evidence processing to support CDFW’s criminal cases and protect California’s fish and wildlife from poaching, exploitation and abuse.

CDFW’s lab is just one of approximately 10 wildlife forensic laboratories in the nation. It works on approximately 100 criminal cases every year and plays a key public safety role by helping to identify the correct species and offending animals in attacks that may involve mountain lions, black bears, coyotes, and even great white sharks.

Born in San Jose and raised in Placer County, Erin holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in genetics from UC Davis.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

From a young age, I always enjoyed math and science. I liked the definitive answers and learning about how things worked. In high school, I had a wonderful biology teacher, and I specifically remember him teaching a unit on DNA. At that time, DNA and genetics were just starting to become more mainstream, and I was just so intrigued with how the DNA bases were essentially translated into the “language” of different functions within the body. I think that was the turning point when I knew specifically what I wanted to study in college.

How did you get to CDFW?

While I was at UC Davis, I started working as an intern and undergraduate researcher with a group that did fish genetics. It turned out that they had a long history of contracts for genetic work with CDFW’s Fisheries Branch, so I had my first exposure to the department there. I was not necessarily interested in sticking with fish genetics as I was becoming more interested in the law enforcement and forensic aspects of DNA. I thought I’d end up working in human forensics at the time.

It was my uncle who worked as one of the hatchery coordinators in the department who connected me with wildlife forensics -- kind of by accident. He told me, “Hey, there are these two guys in Region 2 who walk around in lab coats all the time. I’m not exactly sure what they do, but they have something to do with forensics. You should really look into it.” And so I did.

I ended up meeting Jim Banks, who was a senior wildlife forensic specialist and had been with the department for nearly 20 years. He invited me to come in and learn about the techniques they were using and what some of their investigations looked like. Little did I know he was testing me as a replacement for his scientific aid who was about to go off to graduate school. When she left, I got a scientific aid position at the lab. I guess you could say the rest is history.

Unfortunately, the lab has always been very small. For the majority of its existence, it was run by only two full-time staff and scientific aids, so I was actually a scientific aide from 2000 to 2007. It was a long ride. I obtained a full-time position in 2007 when Jim Banks retired.

Let’s say you’re in a social setting without any CDFW colleagues around. How do you explain what you do for a living?

I usually ask them, “Do you ever watch ‘CSI?’ ” Most of the time they say, “Of course, that’s such a cool show.” And then I say, “Just imagine instead of humans, it’s crimes involving wildlife.” My joke is always that human forensics is boring – you only work on one species. With wildlife, the possibilities are essentially endless.

How many species do you typically work on?

We currently have extensive DNA databases and can do individual matching like they do in human forensics on California deer, elk, mountain lion, black bear, coyotes and wolves. We can also use DNA to identify virtually any animal to the species level. The lab has done cases involving everything from abalone to zebra.

Beyond processing criminal evidence, can you explain the lab’s public safety role?

The lab is called in to assist with DNA analyses on many public safety incidents – especially when there is the potential of physical contact between a person and an animal and the department needs to confirm the species or identity the offending animal. Typically, these incidents involve black bear, mountain lion or coyotes, though we’ve also analyzed attacks by other species – deer, river otter, and great white sharks to name a few. By analyzing the DNA left in the form of saliva around bite wounds or even so-called “touch” DNA from claw wounds, we can verify an attack actually happened, confirm the species involved, and, depending on the species, obtain the genetic profile and sex of the offending animal. This genetic information allows us to compare the DNA profiles of trapped suspect animals with the offending animal’s DNA collected directly from the human victim. When these genetic profiles are a match, we can confirm with statistical certainty that the trapped suspect is indeed the offender. If the profiles do not match, we can free the innocent – which has happened a good number of times.

What do you like best about your job?

I like that we can use DNA to tell the story of what actually happened or what is actually present in each case. Many times, the suspected poachers’ stories or even accounts from people involved in possible wildlife attacks just don’t add up. Sometimes even what our wildlife officers believe to be true from their investigation is different than what the DNA shows. DNA doesn’t lie so letting the science speak and tell the true story is a wonderful tool.

If you had free rein and unlimited funding, what scientific project would you most like to take on?

This is a very difficult question as there are so many projects to choose from. As a forensic lab, we try to watch what the human forensic labs are doing and mimic their methods to the best of our abilities. We are currently watching what is happening with Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) and how this technology will evolve in the forensic community. We are interested in the potential to utilize this to combat issues such as “zone poaching” – killing a deer out of a zone for which the hunter doesn’t have a tag -- or possibly issues regarding hybridization.

With the passage of AB 96 and the resulting new ivory laws in 2015, we are doing more work with wildlife that is trafficked internationally. The demands placed on the WFL have already expanded beyond what we envisioned, resulting in new collaborative efforts and non-DNA-based analyses. I don’t know exactly where any of these paths will lead, but I do know that the WFL will continue to do its best to answer any legal questions through the use of thorough and principled scientific methods.

Tell us something about yourself people would be surprised to learn.

Many people know that I am a lifelong equestrian. I still love to ride and compete, but my secret goal in life is to be on “American Ninja Warrior.” I do a lot of physical fitness type activities, but nowhere near the training needed for that show – yet!

CDFW Photos. Top Photo: Erin Meredith.