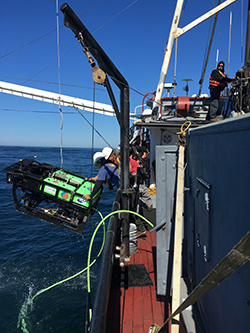

The ROV Beagle (CDFW photo)

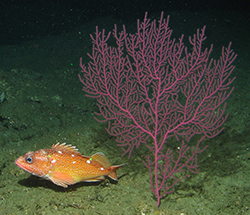

Starry Rockfish from the Channel Islands (CDFW photo)

Yelloweye and Vermilion rockfishes from the North Coast (CDFW photo)

Canary Rockfish from the North Coast (CDFW photo)

Lingcod, white-plumed anemones, female kelp greenling (CDFW photo)

Quillback Rockfish and Basket Stars from the North Coast (CDFW photo)

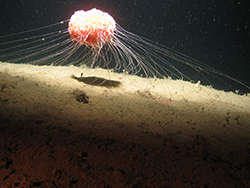

Benthic siphophores use threads to walk and anchor to the seafloor (CDFW photo)

ROV Beagle (CDFW photo by Michael Prall)

Marine scientists from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) and Marine Applied Research and Exploration (MARE) recently completed an unprecedented three-year survey of deep-water habitats off the California coast using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV). Beginning in 2014, MARE’s ROV Beagle was deployed throughout the state to survey and record the species and types of habitats associated with marine protected areas (MPAs) and nearby, comparable rocky habitats.

Surveys were video-based and provided a first look at the many recently established MPAs throughout the state and generated much needed data on abundance and distribution of fish species harvested from rocky habitats.

According to Marine Environmental Scientist Mike Prall, “Many of the areas visited by the ROV Beagle during the surveys had probably never been directly observed by human eyes before our surveys. And all data gathered from video and still imagery collected during the expeditions have provided much needed information about California’s vast deep-water habitats.”

This statewide survey was funded by a $1.9 million research grant awarded to CDFW in 2013 to survey underwater habitats from Mexico to the Oregon border using state-of-the-art underwater technology operated by MARE. In all, five deployments visited over 130 locations and collected hundreds of hours of video in standard and high definition formats, as well as over 50,000 digital still photographs.

Working through MARE’s video processing laboratory in Eureka, trained technicians methodically characterized habitat and identified hundreds of species of fish and invertebrates from high definition video and still photography. Detailed information was also collected from the ROV’s path across the seafloor, which was then used to accurately identify the location of each observation. CDFW scientists used that data for future analysis of abundance, size estimates and patterns of distribution for important species, among other applications.

Preliminary examination of observations from the first ROV deployments have already uncovered interesting findings about species and habitats. In Southern California, small reef patches surrounded by soft sediments showed a high abundance of rockfish in many locations. These habitats are sparsely scattered throughout Southern California’s nearshore waters and may be important to overall fish abundance in areas lacking prominent rocky reefs.

Not surprisingly, the northern California surveys uncovered different findings from those in southern California. Rocky reefs in northern California had patchy distributions of fish, with some areas surprisingly devoid of common species. Strong ocean currents, large waves, and increased sedimentation from rivers created complex dynamics on the north coast and may have influenced the patchy distribution. One striking observation throughout all areas visited statewide was the high abundance of the predatory lingcod.

“Participating in this survey has been a high point of my career at CDFW,” Prall said. “As we continue to work with the massive amount of data gathered, I am excited to see what new results emerge and to see how this work will inform our understanding of California’s amazing underwater resources.”

CDFW scientists and MARE have been collaborating and have explored underwater habitats together throughout California waters since 2003 and have developed highly refined ROV survey methods and processing techniques. Since completion of this endeavor in 2016, this project has provided the most comprehensive and most thorough visual survey of California’s deep water rocky habitats ever attempted.

Information gathered from the data will provide insights into how species may be benefiting from protections afforded by MPAs and give resource managers greater knowledge of managed marine species. CDFW and MARE are currently partnering to survey warty sea cucumber populations in and around Anacapa Island State Marine Reserve. Two deployments funded by the Resources Legacy Fund were completed in 2018. Thanks to this work, scientists now better understand the biology of this important harvested invertebrate species, and in addition, the role of MPAs in the sustainability of the fishery.

Photos taken from the ROV Beagle during the project surveys can be seen on  CDFW's Flickr site. For more information about marine protected area monitoring efforts, visit the CDFW website.

CDFW's Flickr site. For more information about marine protected area monitoring efforts, visit the CDFW website.

Top photo: The ROV Beagle (CDFW photo by Michael Prall)

Media contact:

Carrie Wilson, CDFW Communications, (831) 649-7191