Jennifer Hemmert, Biologist

Survey to assess native rainbow trout at Marion Creek (left to right: Russell Barabe, Tawny Hoemke, Kerwin Russell (Riverside-Corona Resource Conservation District), Paul Nutting, Jennifer in water)

Loading native rainbows rescued from West Fork San Gabriel Creek (Jennifer in truck, Yoselin Caliz, Lauren Hall)

Adult native rainbow trout from Marion Creek

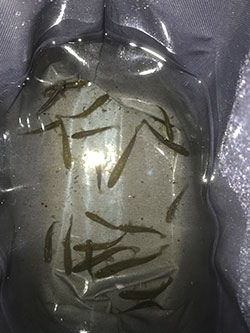

Offspring rainbow trout from Marion Creek

Jennifer Hemmert has taken an interesting route before landing with the Department of Fish and Wildlife as a wild trout biologist and experiencing a career highlight of saving a species of fire-threatened fish three different times. Born in Ohio and a graduate of Ohio State (yes, she is a huge fan of Ohio State football), she has worked in medical research and at a marine park in Hawaii called Dolphin Discovery. Later she worked for the environmental non-profit group Sierra Nevada Alliance as an AmeriCorps member, UC Davis and the state Department of Water Resources. With CDFW since 2012, Jennifer’s trout biology work is done in Riverside and San Bernardino counties.

When did you first know science was a possibility for your career?

Believe it or not, it goes back to grade school. I had an incredible science teacher in the fourth grade, and I knew that biology was my passion. It was his encouragement because he said any student can follow their passion, and if that passion is in math, science, or engineering, one could really shape the future. And so, it goes back to my grade school teacher, Mr. Seas. As a kid, I thought I was going to be either a marine biologist or a veterinarian; I always knew I wanted to work with animals. Also, my focus on fisheries is integrated with my childhood of spending time up on a small lake on the border of Ohio and Indiana. We would spend our summers there fishing, boating and swimming.

What’s a typical day for a wild trout biologist in California?

I work under the Heritage and Wild Trout Program and our mission is to protect the habitats and fish populations within our designated areas throughout the state. We also create recreational opportunities for anglers related to trout fishing. The work is weather-dependent, and in the winter months I am working on reports. There is a seven to eight month window that starts in the spring for field work and we go out in crews of four to six people to do fisheries and habitat assessments on streams in San Bernardino and Riverside counties. We have backpacks that use electric shock, to stun the fish in the streams, and crew members net the fish and place them into buckets. Then we take weight and length measurements on those fish before returning them to the waterway. We are checking on not just the size but also the health and condition of the fish. Through a larger survey, we block the stream with nets and we use the collected electrofishing data to arrive at population estimates.

People might think of those areas as being in the desert. How prevalent are trout and streams in those counties?

As we head south in the state, the quantity of water decreases due to the arid nature. But in the higher elevation streams, there once was historical connectivity for fish to the ocean before humans changed the landscape for the conveyance of water. There were native populations of trout in waters before humans began creating dams and concreting waterways. Some of those populations still exist here in the State and Southern California. The department also creates recreational opportunities by raising trout in two large hatcheries nearby and placing them into waters for anglers. We have two streams designated as wild trout streams. There is Bear Creek, a tributary out of Big Bear Lake, which connects with the Santa Ana River. The second wild trout stream is Deep Creek, which is in the San Bernardino National Mountains and meets up with the Mojave River.

What's the biggest challenge for fish being able to do well, grow and thrive in your region?

A lot of it has to with quantity and quality of water. For fish to thrive, they need cold water and enough water. In times of drought, they can survive extreme and severe habitat changes caused by climate change, but sometimes they need a little help from our staff. Fish are resilient to adapt. They often are challenged by habitat problems that are related to forest fires in fire affected areas.

Since you brought that up, can you talk about an amazing achievement following the Holy Fire in 2018?

The Holy Fire was located in Riverside and Orange counties. Although I’m a fish biologist, I watch forest fires intently and weather forecasts – things not necessarily related to fish, or the biology and species themselves. There had not been a fire in that area for 30 or 40 years, and a lot of vegetation had grown in and was extremely dry. Since the practice of keeping record of where fires burn, there is no information available that Coldwater Canyon had ever had a forest fire. We knew this was an area that would burn very hot and very fast. This fire moved from ridgeline to ridgeline throughout the stream corridor. We work closely with the Forest Service, which studies the amount of sediment that will move through a watershed during a large rain event. It was determined there would be up to hundreds of thousands of cubic yards that would move within most of the surrounding canyons burned by the fire in both Riverside and Orange counties. We needed to move fish from that corridor into our hatchery system.

Which stream did you need to move fish from?

The fish were moved from Coldwater Creek in the Cleveland National Forest, where there was a native trout population. Pre-drought, the population was estimated between 1,000-1,500 trout, and post drought about half of that number survived after four years of these dry conditions. The population estimate was between 400 and 500 fish post-fire, so it was determined we would remove half of the fish from the stream, taking everything we could safely electroshock, and move them into the Mojave River Hatchery.

Did that area have the displacement of debris they were anticipating?

Yes, there was a very large rain event that moved a lot of material into the waterway, as the canyon hillsides had no living vegetation to stabilize now exposed soils. That stream had a chocolate milk appearance after the heavy rain and these fish would have struggled to survive because they would be overwhelmed by the debris. Fish suffocate due insufficient oxygen passing across their gills and the floating sand particles in the water disorientate the fish.

These fish were moved more than once and that’s pretty unusual isn’t it?

Yes, it is unusual. A lot of times fish are taken to a nearby watershed that is not burned. In this case, due to the severity of this fire the nearby habitat was not suitable, so we moved them to the hatchery. Those fish stayed there for about six months before we had a few mechanical issues and had to do an emergency evacuation into Marion Creek in Riverside County, near the town of Idyllwild. We were monitoring the fish in Marion Creek, and were ecstatic to see that they had enough gravel for spawning and were able to naturally reproduce. But it was another dry year and we knew the stream water was significantly decreasing, so in early November we moved them back into Coldwater Creek. The habitat had improved and was suitable again for the fish to be moved back to their home.

How are they doing back at Coldwater Creek?

The habitat is repaired. We have aquatic invertebrates, and we have a lot of willows and vegetation that provide shade, so water temperatures are cold. This year we are looking forward to seeing if we have reproduction and we will assess what the population numbers look like. I want to add that this was done by an entire team of biologists and others from Fish and Wildlife, the Forest Service from both the Cleveland and San Bernardino National Forests, and Riverside Corona Resource Conservation District.

Changing gears a bit, if you weren’t a fisheries biologist what would you have done for a career?

I have always wanted to be a scuba instructor. In my personal life, I scuba dive off the coast of California, Mexico and Hawaii. I always thought I might live and work on an island, where I can have my toes in the sand, watch the sunrise and sunset, and swim with sea life. I have traveled to Honduras twice to scuba dive, plus have done dives in freshwater lakes since I was certified. Alternatively, I also wanted to be a boat captain on possibly a sailboat/dive vessel. After I retire, who knows what and where my next work adventure will take me, but I am sure it will involve water.

What’s the thrill that comes with scuba diving?

A lot of scuba divers like to see the big apex predators that are in the water. But for me, it is all the little fish and little invertebrates, and to be quite honest, seahorses are my favorite. I mean turtles are awesome to see as well as stingrays and sharks, but for me, it is all the little fish. I like seahorses the most.

What’s the attraction to sea horses?

As a child I would always draw seahorses, it was kind of an obsession. I would doodle them all over my notebooks. I am fascinated with how they sway with the currents. They attach themselves with their tails to grasses and their mate and just wave with the currents. They can be camouflaged, colorful and beautiful and are just intriguing to me. Fun facts are that they eat constantly, are horrible swimmers, and mate for life. While these points make seahorses more fascinating as a species, one more critical fact to remember is that ecosystems for all marine life need to be healthy and protected. Pressing threats, such as increasing ocean temperatures and trash as our global marine debris accelerates, continue to be growing problems.

CDFW Photos