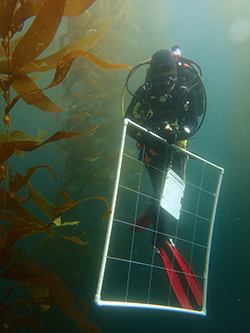

WARC diver Shelby Kawana assesses habitat at one of the CDFW red abalone stocking sites located off the coast of southern California.

WARC diver Armand Barilotti assesses habitat at one of the CDFW red abalone stocking sites located off the coast of southern California.

Octopus are a top abalone predator and therefor pose a threat to newly stocked juvenile red abalone populations. Researchers catch and relocate octopus when they are found hiding in crevasses near stocking sites.

A rediscovered stocked red abalone was found clinging to the underside of a rock during a one year post stocking survey.

Harvesting abalone for dinner used to be as fundamental to a Southern California lifestyle as fish tacos and flip-flops. But by 1998, a combination of overfishing and disease led to the closure of all abalone fishery south of San Francisco. By 2001, the white abalone was listed as an endangered species because populations continued to decline despite protection from fishing pressure. Population numbers are so low today that the only option for recovery is believed to be through a robust captive breeding and stocking program.

Scientists from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) White Abalone Recovery Project and their partners in the White Abalone Recovery Consortium (WARC) are working to bring back the iconic white abalone from the brink of extinction. Since 2016, CDFW and partners have been working to actively restore abalone populations through stocking of young captive-reared abalone. Successful stocking is the critical next step to reestablishing self-sustaining wild populations of this culturally and ecologically important mollusk. The early stocking studies have aimed to perfect the methods that will be used to restore wild white abalone populations in the future by using red abalone as a test case. Red abalone, a sister species of the white abalone, lives in the same deep kelp forest habitats, and their populations in Southern California have also been very slow to recover.

Every few months, scientific divers on board the CDFW research vessel Garibaldi wrestle into thick neoprene wetsuits and load heavy steel tanks onto their backs in order to check on the stocked abalone. As the divers descend deeper into the kelp forest, they enter the world of the white abalone. Sunlight streams through the towering giant kelp, briefly illuminating the shiny sides of the small fish taking cover in the kelp blades. Lobsters and octopuses are tucked into the crevices of rocks, and abalone and urchins shelter in the shadows. Many of those abalone are adorned with small brightly-colored numbered tags that identify them as the new additions to the neighborhood. After a few months in the wild, the stocked abalone can show an extensive amount of growth which speaks to the quality and abundance of resources in their new habitat.

Since restoration stocking began in 2016, the partnership has stocked close to 10,000 red abalone off the coast of southern California. These studies are helping scientists understand how stocked abalone interact with their new environment in the wild. Researchers are increasing the effectiveness of future stocking work by teasing out the risk factors that abalone face in their new environment. For multiple years after releasing the abalone, divers track the number and identity of each abalone, and assess the ecosystem health and predator abundances at each site. The divers also collect any abalone shells encountered to determine the effects of different predators at each site through time.

Octopuses, lobsters, sea stars and fish are all major predators of the young abalone, and care is taken to introduce the abalone during times of the year when the predators will be least abundant. All of the data from these early studies are aimed at lessening the risks that stocked abalone face, and to improve long-term growth and survival.

The WARC understands that abalone are at the heart of coastal California’s identity and culture. The return of red and white abalone to the wild marks the beginning of a new chapter in the love story between California and this amazing mollusk. This is true for the ecosystems that rely on them as well as for the humans that cherish them. Please stay tuned for updates on the lessons learned from these studies, and plans for upcoming white abalone stocking work!

For more information, please visit the following pages:

CDFW Photos. Top Photo: Newly tagged red abalone that are ready to be released into the ocean during a WARC stocking study in 2016.