With less competition from non-native species, native Lahontan cutthroat trout are growing larger in Silver Creek.

Amid the intense, physically demanding native trout restoration work taking place in the fall of 2022 on Silver Creek, Mono County, Nick Buckmaster allowed himself a momentary indulgence.

A senior environmental scientist supervisor with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), Buckmaster paused long enough to imagine himself camped on the banks of Silver Creek within the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest, perhaps on vacation, maybe in retirement. It was a warm, summer evening in his mind’s eye, and Buckmaster was casting a dry fly to rising wild and native Lahontan cutthroat trout in the 14- to 16-inch size class.

Such a scenario would have been unthinkable just a couple of years ago. Silver Creek has been closed to fishing of any kind for almost 30 years to protect the remnant population of native trout. Overrun with more aggressive, non-native brook trout despite attempt after attempt to remove them, Silver Creek’s Lahontan cutthroat trout (“LCT” in fisheries parlance) have been clinging to a marginal existence within their home waters.

Today, however, Buckmaster’s dream is closer to reality than it has been in a generation. The Lahontan cutthroat trout recovery work taking place in Silver Creek the last few years represents one of the largest and most ambitious wild and native trout restoration efforts in California history. And nowhere else throughout the Great Basin where Lahontan cutthroat trout were once so abundant is this recovery work happening more quickly, more innovatively and more successfully than in little Silver Creek.

And many eyes are on Silver Creek, a tributary of the West Walker River located about 20 miles northwest of Bridgeport in the hills above the Marine Corps’ Mountain Warfare Training Center. The recovery work there, which will resume in the summer of 2023 as snowmelt allows, is taking place at a moment when federal and state wildlife officials are seeking to accelerate Lahontan cutthroat trout recovery throughout the West. The fish have languished as a listed species under the federal Endangered Species Act for more than 50 years.

Buckmaster and his supervisor, Environmental Program Manager Russell Black from CDFW’s Inland Deserts Region, took on the Silver Creek recovery project in 2020 during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic when social distancing and stay-at-home mandates shut down a lot of other field work. New to the project and passionate about wild trout, the two were either unburdened by decades of past failures at Silver Creek or simply naïve to conventional thinking that Silver Creek and its genetically pure strain of Walker River Basin Lahontan cutthroat trout were a lost cause.

The two supervising fisheries biologists were also on something of a roll having led CDFW’s successful, five-year effort to rescue the federally endangered Owens pupfish, a species so rare it was once declared extinct. That undertaking opened up several square miles of additional pupfish habitat after the removal of non-native, predatory species and helped improve genetic diversity, capturing the imagination of The New York Times in the process.

The same dewatering techniques Buckmaster and Black deployed in the lowlands of the Owens Valley to eliminate non-natives and help pupfish are proving equally effective in the mountains of Mono County to help Lahontan cutthroat trout. Applying those techniques to a small stream environment was a first. For CDFW staff new to the project, training was held last spring at nearby Slinkard Creek (YouTube).

By mid-September, Buckmaster was leading a 10-person crew of fellow fisheries biologists and scientific aids over eight consecutive days of intense field work that involved temporarily lowering flows in portions of Silver Creek (sometimes for a mile or so at a time) to remove the brook trout and relocate the Lahontan cutthroat trout to higher, previously treated reaches upstream that are now brook-trout free. It was Buckmaster’s sixth trip and treatment of Silver Creek of the eight he and his CDFW colleagues would conduct in 2022.

Last year was also a milestone in that CDFW was able to treat all 11 miles of Silver Creek and its tributaries targeted for brook trout removal. The work began at the meadowed, headwaters section and extended 9 miles to rocky, pocket water downstream where a steep waterfall prevents brook trout from moving up into Silver Creek’s higher reaches and best trout habitat.

The goal is not suppression but total removal of the non-native trout within those 11 miles of prime habitat.

“If you leave two brook trout in the system and one happens to be male and the other happens to be female, you’ve lost,” Buckmaster said. “The brook trout will repopulate and take over the creek. And in that case, we might have just as well stayed home and watched football.”

Dewatering Silver Creek begins with installing a temporary sandbag dam. Large, flexible poly pipe not much thicker than a heavy-duty trash bag is attached to the dam, rerouting most of the creek flow more than a mile downstream. Below the dam, the creek is subdivided into quarter-mile sections with barriers installed to block fish movement.

With Silver Creek’s flow significantly reduced and the trout concentrated in the remaining water, electrofishing teams move in, stunning the fish with electrical current and netting those that float toward the surface. The Lahontan cutthroat trout, outnumbered by brook trout 10 to one in Silver Creek’s lower reaches where the September work occurred, are collected and separated from the brook trout. They are measured, recorded and moved upstream of the sandbag dam and released into previously treated sections of the creek. The brook trout are set aside in buckets for later stocking into nearby Kirman Lake for recreational fishing.

Following the initial electrofishing, separate CDFW teams move in with portable pumps to dry up any last remaining pools and puddles that may still be harboring fish. The crews continue to electrofish, move rocks, look under tree roots and probe crevices for fish. A third “clean-up crew” follows behind the pump teams to triple-check the work as water slowly begins to return. The process is repeated over multiple days and over multiple trips.

“No matter how many passes you do with the electrofishing equipment, you keep finding fish until you completely dewater the creek,” Buckmaster said.

While painstaking and physically demanding, dewatering has proven more efficient, less costly and more environmentally friendly than alternative recovery measures used in the past.

CDFW treated Silver Creek with Rotenone in 1994, 1995 and 1996 only to see brook trout return in the early 2000s. Over the past 20 years or so, a variety of government agencies, conservation organizations, fly-fishing clubs and other permitted volunteer groups have also contributed to recovery efforts with periodic brook trout removal. And yet the non-natives persisted.

“Dewatering is an amazing tool,” explained CDFW’s Black. “We’re able to both remove the invasive species and at the same time put that native species right back into the system the same day. That’s having a real positive benefit for LCT while not impacting the creek or the invertebrate community.”

Restoring Silver Creek for Lahontan cutthroat trout has positive ramifications for other native species. As the brook trout population is eliminated, CDFW scientists are encountering more Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frogs. As Silver Creek becomes more hospitable to Lahontan cutthroat trout, it paves the way for the potential reintroduction of other native fish such as speckled dace, mountain whitefish and mountain sucker.

“It’s an all-around win for all native species in what’s a climate-resilient habitat,” Buckmaster said.

Among the end goals, said Black, is to reopen Silver Creek once again to recreational fishing, most likely as part of CDFW’s Heritage and Wild Trout Program, giving anglers a chance to catch wild Lahontan cutthroat trout in their native habitat in a spectacular setting. That prospect may still be a few years away. Black estimates Silver Creek will need two or three additional seasons of dewatering treatments to confirm the complete absence of brook trout. Subsequent monitoring could also be accomplished through eDNA, which can detect brook trout presence simply by testing water samples.

Since 2020, about 15,000 brook trout have been removed from the system, and Lahontan cutthroat trout appear to be thriving in Silver Creek’s upper reaches that are now mostly brook-trout free after multiple dewatering treatments.

“We’re seeing young-of-the year LCT in the headwaters, which we’ve never really seen before, and we’re getting large numbers of adult fish in the system in the 1- to 2-year-old age class,” Black said.

Last fall, some of those adult trout measured 12- to 14-inches in length. It’s the stuff of fly-fishing dreams.

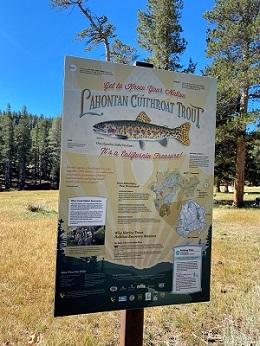

CDFW Photos: Wild trout experts Allison Scott and Gabriel Singer probe for brook trout as a portion of Silver Creek is pumped dry. Signage along Silver Creek proclaims Lahontan cutthroat trout a "California Treasure" and directs anglers to nearby waters that are open to fishing for the native species. Large, flexible poly pipe reroutes most of Silver Creek's water flow around the work zone targeted for brook trout removal. Nick Buckmaster surveys the work taking place at Silver Creek in the fall of 2022.

###

Media Contact:

Peter Tira, CDFW Communications, (916) 215-3858