New research by CDFW Wildlife Ecologist Dr. Brett Furnas shows that Neotropical migrant songbirds are shifting their summer ranges to higher elevations in response to climate change.

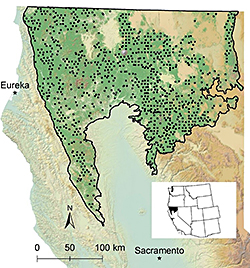

Locations of bird surveys throughout Northern California in a region representing more than 40 percent of all California’s coniferous forests. CDFW has been monitoring wildlife at these locations since 2002 to help inform conservation efforts. Photo courtesy of Dr. Brett Furnas.

An automated sound recorder used to survey songbirds. These devices were programmed to make three 5-minute recordings before, at, and after sunrise –repeated over three consecutive mornings. The timing of the recordings is significant because different species tend to sing at different times in the morning. Photo courtesy of Dr. Brett Furnas.

An automated sound recorder used to survey songbirds. These devices were programmed to make three 5-minute recordings before, at, and after sunrise –repeated over three consecutive mornings. The timing of the recordings is significant because different species tend to sing at different times in the morning. Photo courtesy of Dr. Brett Furnas.

New research shows climate change may harm migratory songbirds. Saving their forest habitat may help.

Songbirds that travel to northern California each summer from winter ranges in Central and South America appear to be more sensitive to climate change than other types of songbirds, according to new research by CDFW Wildlife Ecologist Dr. Brett Furnas.

In a new paper published in the journal Biological Conservation, Dr. Furnas analyzes 14 years of data taken from the surveys of songbirds living in northern California conifer forests. The bird surveys were done in the Klamath Mountains, Southern Cascades and North Coast Ranges, a region representing 42 percent of all conifer forests in the state.

“The data is especially significant because it is representative of such a large region,” said Dr. Furnas.

Research was completed using automated sound recorders which captured the calls of songbirds at over 1,000 sites between 2002 and 2016. Birds were surveyed at their annual summer breeding grounds about a month after arriving from their winter homes.

Dr. Furnas studied three types of songbirds: year-round residents; short-distance, altitudinal migrants which winter at lower elevations and breed at higher-elevations; and long-distance, Neotropical migrants that winter in Mexico, Central America and South America and breed in California.

“The research alone is an amazing part of this story. Each of the 1,000-plus survey sites required someone to drive to the middle of the forest, hike for an hour or more and install survey equipment,” said Dr. Furnas.

The data shows that Neotropical migrant songbirds are shifting their summer ranges to higher elevations where the climate is cooler. But there’s a downside to the new migration pattern: The long journey reduces the Neotropicals’ flexibility when it comes to breeding behavior. Adjusting to changes in temperature and available food resources in California ultimately hurts their reproductive success.

“Neotropicals’ sensitivity to climate change makes them a conservation risk. It’s unclear if they can adapt as climate continues to warm,” said Dr. Furnas.

There was less evidence of elevational shifting for resident and altitudinal songbirds, indicating they might not be as vulnerable to increases in temperature. This is likely because species that migrate shorter distances – or don’t migrate at all – have more time to prepare for the breeding season. They also have more time to establish a territory, sing to attract a mate and gather food to help raise a brood.

The Neotropicals’ vulnerability is exacerbated by other factors as well. One consequence of the compressed breeding cycle is that the birds can’t afford to tone down singing on hot days when it becomes metabolically taxing. In contrast, resident birds tend to sing less on hot days.

Dr. Furnas sees conservation of mid-elevation conifer forests as part of the solution. Neotropicals are expanding their range to about 5,000 feet and above.

“Middle-elevation conifer forests appear to have features of natural climate refugia. Conserving these forests is crucial,” he said.

However, the natural climate refugia identified by Dr. Furnas have their own vulnerabilities. “If you think of mountains like a triangle, there’s less land area in the middle-elevation forests that Neotropicals are shifting to than in the lower elevation forests they’re abandoning. The availability of forest habitats at higher elevations could be limited in the future due to faster rates of warming at those elevations,” Dr. Furnas said.

For these reasons, the middle zone is a sweet spot for birds. “An increasing number of birds will be crowding into this sanctuary,” he said.

Dr. Furnas’ ultimate message is that research with an emphasis on biodiversity monitoring will be essential to future conservation efforts. Research based on biodiversity monitoring can help identify species and habitats that are most in need of conservation. It can also help conservationists and policy makers assess the effectiveness of conservation actions.

Read Dr. Furnas’ paper:  Rapid and Varied Responses of Songbirds of Climate Change in California Coniferous Forests

Rapid and Varied Responses of Songbirds of Climate Change in California Coniferous Forests

CDFW Photos. Top Photo: Long-distance Neotropical migrants like the Hermit Thrush may be more vulnerable to climate change than other types of songbirds.

Media Contact:

Ken Paglia, CDFW Communications, (916) 322-8958