The MLMA emphasizes the importance of collaboration in achieving its objectives as well as the value of capitalizing on the expertise and resources that exist outside of the Department (§7056(k)(opens in new tab)). Collaboration involves working with interested parties on some aspect of the management process and can vary significantly with respect to responsibility-sharing, structure, and duration. Collaborations can operate across a broad spectrum. On one end of the spectrum is stakeholder engagement, which involves the Department soliciting targeted input on specific management actions. On the other end are partnerships that are more formal, structured, and often intended to be longer-lasting. This chapter focuses on partnerships, their benefits, and the conditions necessary for them to achieve their purposes. It draws from an overview of partnerships in California’s fisheries developed as part of the information gathering phase for the Master Plan amendment process (Wilson et al. 2016). See Appendix P for additional details.

To meet the MLMA’s objectives regarding collaboration, the MLMA encourages the Department to:

- Involve all interested parties in marine living resource management decisions (§7050(b)(7)(opens in new tab)).

- Manage fisheries in a way that is collaborative and cooperative (§7056(k)(opens in new tab)).

- Find creative new ways to involve outside experts with the necessary expertise at colleges, universities, private institutions, and other agencies (§7059(a)(2)(opens in new tab)).

- Use the collaborative process to develop FMPs, research plans, status reports, and other management documents (§7059(a)(3)(opens in new tab)).

- Periodically review marine life and fishery management operations with a view to improving communication, collaboration, and dispute resolution, seeking advice from interested parties as part of the review (§7059(b)(1)(opens in new tab)).

- Develop a process for the involvement of interested parties appropriate to each element in the fishery management process (§7059(b)(2)(opens in new tab)).

- Consider the appropriateness of various forms of fisheries co-management when developing and implementing FMPs (§7059(b)(3)(opens in new tab)).

- Consider the gear used, the involvement of different commercial, recreational, or processing sectors, and where the fishery is conducted to ensure adequate involvement of fishery participants (§7059(b)(4)(opens in new tab)).

- Use collaborative approaches to collect EFI (§7060(a)(opens in new tab)).

- Encourage the participation, collaboration, and cooperation of fishermen in research design and data collection (§7060(c)(opens in new tab)).

- Consider contracting with qualified individuals or organizations to assist in the preparation of FMPs (§7075(b)(opens in new tab)).

- Seek advice and assistance from participants in the affected fishery, marine scientists, and other interested parties when developing FMPs (§7076(a)(opens in new tab)).

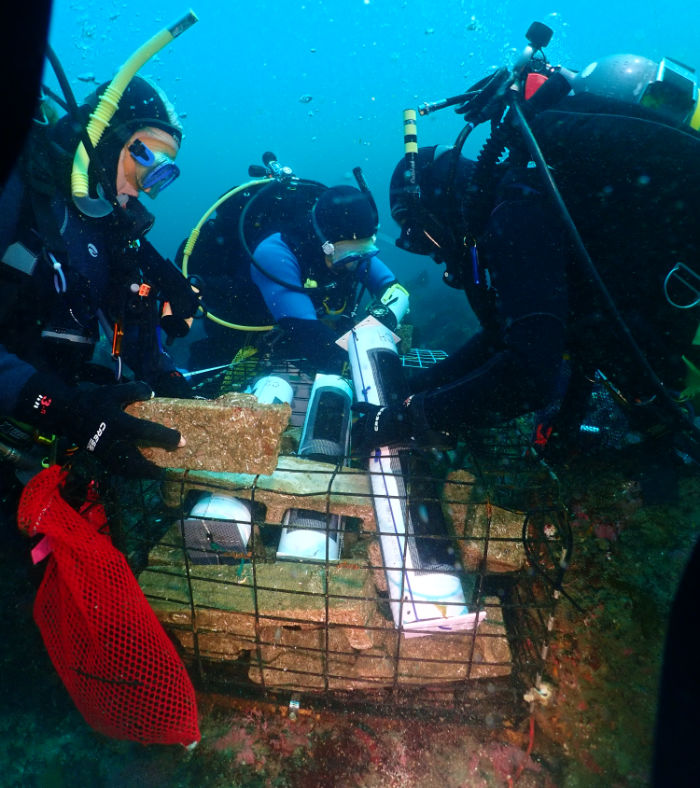

CDFW and NOAA Fisheries collaborative effort to outplant hatchery-raised white abalone. (CDFW photo by Ian Tanaguchi)

CDFW and NOAA Fisheries collaborative effort to outplant hatchery-raised white abalone. (CDFW photo by Ian Tanaguchi)

Benefits

California is home to engaged fishermen, active NGOs, a wide range of academic and research institutions, Tribes and tribal communities, and public and private funding institutions that are interested in responsible fisheries management and helping the Department and Commission advance the goals of the MLMA. Well-structured partnerships can help to support short- and long-term fishery management goals and enhance and increase the state’s capacity to effectively manage fisheries under the MLMA. In the face of increasingly variable ocean conditions, partnerships can provide an effective mechanism to promote ecological, social, and economic resilience. In addition, partnerships can consider and use varied skill sets as well as have direct benefits to fisheries managers. For example, Collaborative Fisheries Research (CFR)(opens in new tab) presents a valuable opportunity to engage stakeholders in the identification of research needs, design of research efforts, collection of data through field work, and interpretation of results.

The following are examples of potential benefits of fisheries partnerships (Wilson et al. 2016):

Ecological benefits

- Fisheries maintain sustainable stock levels with long-term stability in abundance and stock health.

- Improved conservation of sensitive habitats, nursery grounds, and spawning grounds.

Economic benefits

- Potential decrease in Department’s management cost.

- Potential increase or maintained revenue streams through stabilized landings, and reduced risk of fishery collapse by improving assessments and harvest levels that reflect actual stock sizes.

Political benefits

- A more democratic and participatory system where the interests of government, fishermen, and community members become better aligned.

- Reduced conflict in decision-making.

Benefits to the Department

- Increased support for cost and task sharing opportunities, creating the potential for more efficient and productive management over time.

- Support and buy-in for fisheries management regulations and policies leading to enhanced compliance and better working relationships with industry and NGOs.

Partnership continuum

Fisheries management consists of a wide variety of tasks, each presenting specific opportunities for partnership opportunities. Figure 5 shows categories of common management tasks ordered by the degree of capacity that is needed by partners to effectively engage in a partnership. For these purposes, partner capacity is proposed to consist of three characteristics: 1) how representative the group is of the broader community; 2) the resources the group has available to allocate to the partnership; and 3) how long-standing and durable the partner is.

Partnerships that involve sharing responsibility for more inherently agency-led functions will require more organizational capacity on the part of the partner. While situations will vary, tasks should be closely matched with the partner’s capacity to help to ensure a successful partnership. See

Appendix P for additional details.

Figure 5. A continuum of partnership-based approaches (adapted from Wilson et al. 2016). The management tasks and types of partnerships are arranged along this continuum in terms of how much organizational capacity, funding and longevity is required for successful partnerships to help meet management objectives or tasks.

Figure 5. A continuum of partnership-based approaches (adapted from Wilson et al. 2016). The management tasks and types of partnerships are arranged along this continuum in terms of how much organizational capacity, funding and longevity is required for successful partnerships to help meet management objectives or tasks.

Inquiries to assess prospective partnerships

If a partnership is well-designed, it can help to advance the objectives of the MLMA. If not, it can distract from other high-priority activities and frustrate partners. To assess a prospective partnership, the Department should consider the inquiries below. These are not intended to be prescriptive or formulaic; rather they are provided to help managers carefully consider prospective partnerships to help to ensure they advance the goals of the MLMA.

Regarding the partnership

- Will the partnership advance an identified research or management goal?

- Is there trust among partners or the ability to build trust through the partnership?

- Is there an identified source of funding or capacity to support the partnership?

- Will the partnership involve the exchange of knowledge and information necessary to accomplish the goals of the project?

- Will the partnership place a management burden on Department staff disproportionate to its benefits?

Regarding the partner

- What is the partner’s motivation to engage?

- Does the partner have effective leadership?

- What is the partner’s long-term relationship with the resource or stakeholders who target the resource?

- Does the partner have the necessary capacity to effectively collaborate on the proposed task?

- What unique knowledge or skills regarding the resources does the partner have?

- What is the partner’s historical or cultural connection to the resource?

- What is the partner’s economic or social reliance on the resource?

- How compatible are the partner’s interests and uses with those of other stakeholders?

Release of hatchery-raised white seabass. (CDFW photo)

Release of hatchery-raised white seabass. (CDFW photo)

Engaging in constructive partnerships

Once the decision to engage in a partnership has been made, there are number of best practices that can help to ensure the partnership is productive. These are informed by the Department’s own considerable experience with partnerships. Examples include the Department’s engagement with the steering committee developing the Pacific Herring FMP, and the efforts to address management needs of the Dungeness Crab fishery by the California Dungeness Crab Task Force.

Guidance

- Develop clear goals, roles, and objectives at the outset of the partnership.

- Ensure regular and effective communication among parties.

- Ensure transparency by informing stakeholders outside of the partnership of its goals.

- Provide stability and direction to partnerships involving multiple groups with diverse perspectives.

- Plan ahead for anticipated funding, resource requirements, and/or uncertainties regarding the partner’s longevity to remain engaged.

- Periodically evaluate if the partnership is meeting its goals and how it affects staff workload and the ability to meet other obligations.

The Master Plan was developed through an extensive suite of partnerships that contributed information, tools, and resources. Similarly, full implementation of the Master Plan will require additional capacity and well-designed partnerships to effecti

vely carry out its strategies and achieve its goals.