Market Squid Reproducing. Photo credit: Mark Conlin Photography

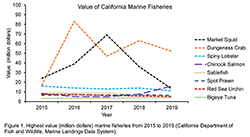

Highest value marine fisheries, 2015-2019 - click to enlarge

Squid fishing fleet near Monterey. CDFW photo by Carrie Wilson - click to enlarge

Squid fishing fleet at night. CDFW photo by Carrie Wilson - click to enlarge

Arriving on the heels of the farm to fork movement, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted supply chains and altered product demand, which has inspired businesses to restructure and Californians to pay particular attention to where their food comes from. Many understand that almonds, artichokes or lettuce are grown in their own backyard, mostly in the Central or Salinas Valleys. But when residents are asked about wild-caught food sources coming from the ocean, tuna, salmon or perhaps rockfish might immediately come to mind. While those are indeed popular fisheries, the largest of California’s commercial fisheries actually target invertebrates, not fish!

Invertebrates are animals without a backbone, such as the tidepool favorites, sea stars and anemones. But there are many more invertebrates around the world, both swimming and sedentary, that are highly sought after for food – and their popularity is on the rise. California’s largest marine commercial fisheries in terms of volume and value are market squid and Dungeness crab, with well over 100 million pounds landed and more than $30 million in revenue in a typical year for the squid fishery.

Market squid, the invertebrate known to diners as the popular dish calamari, use ocean currents, jet propulsion and prehistoric instincts to travel up and down the continental shelf of California. These slippery siblings of octopuses live very short lives (less than nine months) and produce heaps of eggs, somewhere on the order of 2,000 to 7,000 per female!

When conditions are right, squid show up in droves to reproduce in coastal waters. After reproducing for just a few short days, they die as a natural part of their life cycle. This means the entire population replaces itself in less than a year. These qualities lend to a high volume of squid available for fishermen, cost-effective management and a sustainable fishery. Squid are also used as bait to catch a wide variety of fish species and can be found at many coastal tackle shops or on live bait barges, mostly in Southern California.

If you see very bright lights from groups of boats on the water at night, it is likely the squid fishing fleet in action. Fishermen have used this technique for more than a century because squid are attracted to the lights, which mimic the moonlight. As described in an historic Fish Bulletin from 1965, the market squid fishery began in Monterey around 1863. The early fishing methods involved rowing a skiff with a lit torch at the bow to aggregate the squid. Then, two other skiffs would maneuver a large net around the school.

In today’s fishery, squid are typically caught using a purse seine, a large circular net which is “pursed” at the bottom to contain the school. Once the school of squid is brought closer to the vessel, a long tube is then used to suck the squid out of the net and onto the boat.

Only a limited number of vessels may fish for squid in California, and during the weekends (from Friday afternoon to Sunday afternoon) squid fishing is closed to allow for uninterrupted reproduction. In many fisheries, highly sophisticated mathematical models are used to estimate the available population for an upcoming season and ultimately to decide how many fish can be sustainably caught. Because market squid are short-lived, highly responsive to ever-changing environmental conditions and do not behave like most fish, traditional models are ineffective.

For this reason, the fishery is monitored using the egg escapement method, which is essentially an estimate of how many eggs are released prior to female squid being caught. By comparing the average number of eggs that a female squid will produce to squid samples collected at the docks, biologists can calculate how many eggs were produced each year. This is used to look for trends or major shifts in how the squid fishing fleet is interacting with the stock. Biologists continue to explore ways to pair egg escapement information with population estimates, environmental variables, fishing behavior and economics.

Fishing for market squid is a long-standing tradition in California and normally provides for a large export market. But a number of recent factors, including the COVID-19 pandemic, have inspired stronger local markets for many fisheries, such as squid. This means more restaurants, businesses and consumers are buying directly from the docks, shortening the distribution chain. Boat captains, crew, processors, distributors and diners eagerly await the arrival of squid, especially around spring and summer on the central California coast when fishing is generally the most successful. If history repeats itself, vessels will move to Southern California in the fall and winter, where the Channel Islands tend to be the hot spot for squid fishing. But in response to a changing climate, the range for this species is likely to expand northward, forcing the fishing industry and the biologists studying squid to adapt as well!

###

Media Contact:

Kirsten Macintyre, CDFW Communications, (916) 804-1714.