Christy prepares for a day’s work underwater at La Jolla.

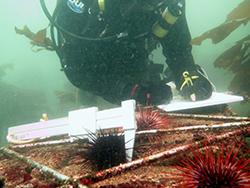

Christy Juhasz works on an abalone density survey off the northern California coast.

CDFW Environmental Scientist Christy Juhasz works for the Marine Region’s Invertebrate Management Project, where she is primarily responsible for managing California’s Dungeness crab fisheries. Christy coordinates preseason quality and domoic acid testing for the commercial fishery, summarizes seasonal landings data and works on rulemaking proposals for both the commercial and recreational Dungeness fisheries.

A Southern California native, Christy earned a bachelor’s degree in marine biology, with a minor in oceanography, from the University of California, Los Angeles. Soon after graduating, Christy’s first paid position involved monitoring and trapping the invasive European green crab in several northern California bays and estuaries. Afterwards, she began working for CDFW as a scientific aid at the Shellfish Health Laboratory, located at the Bodega Marine Laboratory in Bodega Bay, where she spent several years testing quality control measures of a sabellid, polychaete worm that had been introduced at aquaculture facilities.

In 2007, she became a certified CDFW diver and began assisting in abalone density surveys conducted on the Sonoma and Mendocino coasts. In 2011, she was hired in her current position to work on Dungeness crab fisheries management.

What led you to a career in marine biology?

As a child, I spent an inordinate amount at the coast and particularly enjoyed exploring tidepools. I was always fascinated by the creatures that eke out an existence on the water’s edge, fostering my love of marine invertebrate species. This only grew after taking an invertebrate taxonomy course, becoming certified in scientific diving and volunteering at a small, local marine aquarium while in college where I was able to share my love of native California marine life with the public.

Not many people can say they get to dive as part of their job duties. What’s that like?

Before coming to work at CDFW, most of my diving experience was in the warmer waters of Southern California and the Bahamas for training and research, respectively. Diving in the colder and rougher northern California ocean waters has been interesting. My job has taken me to some beautiful underwater habitat where diverse and colorful kelps, invertebrates and rockfish species abound, while also making me a much better diver.

One interesting CDFW dive location includes the site of Mavericks, although not at the height of the surfing season. We were there to assess the red abalone population within the Marine Protected Area and I was able to observe firsthand the effects of the intense wave action that had eroded away the subtidal rocky reef promontories.

How frequently do you get to dive?

Recently, I had my first child so have not been able to get back underwater as intensely since before I was pregnant. Prior to this, I was an active CDFW diver, primarily assisting with monitoring red abalone populations in the summer months. Diving and field work, in general, are always fun to go out and do in coastal locations, but they do require a lot of planning and preparation. Actual collection of data while SCUBA diving really teaches you to be in the moment, as you have multiple tasks to complete underwater. Obviously safety is paramount and you have to pay attention to the air you consume while you’re working, which ultimately limits the amount time you have underwater.

Today, most of your work relates to Dungeness crab. What do you find interesting about this particular fishery?

The Dungeness crab commercial fishery is one of California’s highest valued fisheries and is also one of the state’s oldest fisheries. In fact, regulations governing take of legal-sized males around a set seasonal period date back to the turn of the 20th century, and are known as the 3-S management principle (sex, size and season). The fishery does widely fluctuate from season to season, but with California landings dating back to just over 100 seasons, there have been no observable, long-term crashes in catch history. In recent seasons, the fishery has experienced some record landings in both management areas of the fishery, especially in the central region, which in the past decades rarely contributed to the majority of statewide landings.

I enjoy and thrive in my job under the dynamic and varying responsibilities and tasks that support the operations of the fishery. Whether I’m working on rulemaking packages, meeting with constituents for various issues or incorporating new or more extensive sampling procedures – it’s all very interesting.

Do you work with species other than Dungeness crab?

Yes. Some of my monitoring and rulemaking work involves other invertebrate fisheries in California, which have been increasing in importance (see link to journal article below). This raises new challenges for fisheries managers, especially considering the many invertebrate fisheries we oversee and the various life history strategies characteristic of each species.

For instance, red urchin and red abalone have to be relatively near one another for successful fertilization after they release their gametes into the water column. This is in contrast to Dungeness crab, which mate during the period when females molt, and brood eggs before they hatch. These differences just reveal how each fishery requires a unique set of regulations to effectively manage them.

What is the most rewarding project that you’ve worked on for CDFW?

I have been collaborating with other CDFW staff to monitor the arrival of the Dungeness crab megalopae – that’s the last pelagic, larval stage of crabs before they molt and settle to the bottom as juveniles – to California’s bays and estuaries. The study aims to determine if there is link between their relative number and size, and perhaps predict commercial catch three to four years later, which is about when these crabs would grow into the fishery. Work on this is still preliminary, but in the time we have been observing, we have noticed big differences in total numbers and average size. This may be driven by optimal ocean conditions since the planktonic larval stages spend an average of four months total in the water column during the winter and spring months.

I’m also involved in the rulemaking process for the Dungeness crab commercial fishery. One current development is the creation of a formal statewide program for incentivizing the retrieval of lost and abandoned Dungeness crab traps at the end of each season. The fishery has rules in place such as the use of a destruct device that wears away, to allow escapement and prevent a lost or abandoned trap from continuously capturing organisms. However, traps attached to a buoy with vertical lines in the water column that remain in the water past the season pose additional hazards to marine life and vessel traffic. The industry has been piloting local programs for the past several seasons. A formal program is expected to be in place by the end of the 2018-19 season.

Recent seasons of the Dungeness crab fishery have been plagued by high domoic acid levels and low quality, leading to season delays. How has this changed the nature of your work?

The pre-season quality testing has been conducted for the northern portion of the fishery for many years in concert with Washington and Oregon testing. Although procedures have been modified over the years, the scheduled delays are built into the current operations of the fishery. The fishery cannot be delayed due to quality issues past January 15, whereas with domoic acid season delays are unpredictable.

Our efforts to monitor Dungeness crab are more extensive before the start of the season. Dungeness crab fishermen are key players in this task, as I call and email with them to collect and retrieve samples throughout the fishery’s range statewide (this is similar to how the quality testing is conducted as well). I also coordinate with staff from the California of Department of Public Health to ensure that samples collected are properly received by their laboratory testing facility. During the 2015-16 delayed season, CDFW staff worked tirelessly on this sampling effort while navigating the problem under current regulations and effectively communicating the latest information on the status of the delay and potential opening of the season. This was especially important in light of lost revenue due to the unforeseen delays.

Do you expect that domoic acid will continue to be a problem in future seasons?

Domoic acid is a neurotoxin produced by a unicellular algal organisms that thrive in warm water. The domoic acid problem that caused the severe delay of the 2015-16 season was thought to be a direct effect of the anomalous (unusual) ocean warming from the “warm blob” that developed off of US West Coast in 2014. As these anomalous warming ocean conditions persist, so does the problem of harmful algal blooms that cause domoic acid. This has become a top priority for discussion between industry, the Dungeness crab task force and other affected fisheries and agencies.

CDFW Photos. Top Photo: Christy measuring a dungeness crab.

For Further Reading: